New clinic expands brain metastasis treatment options

MD Anderson’s Brain Metastases Clinic is streamlining treatment and offering more options for patients with brain tumors that are notoriously difficult to treat.

Cancer cells that escape their original site and travel through the bloodstream to the brain find a supportive sanctuary there, where they grow and often cause significant neurological symptoms.

These brain metastases, or secondary brain tumors, are notoriously difficult to treat because they’re resistant to many cancer treatments, and they live behind the blood-brain barrier – a semi-permeable membrane that keeps the brain “safe” from toxins in the blood. When cancer cells invade the brain, the blood-brain barrier transitions into the blood-tumor barrier, which still presents a roadblock for effective drug delivery to the brain.

“This makes brain metastasis one of the most difficult challenges in oncology,” says Frederick Lang, M.D., chair of Neurosurgery. MD Anderson has led the way in meeting this challenge with innovative clinical trials that are changing the prospects for brain metastasis patients, who used to be routinely excluded from tests of new drugs.

Last year, medical oncologists, neurosurgeons and radiation oncologists teamed up to launch MD Anderson's Brain Metastases Clinic. The goal is to sharpen their efforts and provide patients with more convenient and efficient care.

“Our Brain Metastases Clinic enhances the patient experience, our clinical decision-making and our research efforts against these tumors,” says Lang, one of the clinic’s three co-leaders.

Standard brain metastasis treatments

Any cancer can spread to the brain, but the types most likely to cause brain metastases include melanoma, lung and breast cancers. For most patients with multiple brain metastases, treatment typically involves surgery, radiation therapy or both.

For decades, whole-brain radiation therapy has been the primary treatment for patients with multiple brain metastases. While the treatment didn’t cure the cancer, it extended progression-free survival and reduced symptoms, such as paralysis and headache caused when tumors increase pressure inside the skull.

“But whole-brain radiation can also cause cognitive problems by diminishing a patient’s short- and long-term memory, problem-solving skills, attention span and word recall,” says Jing Li, M.D., associate professor of Radiation Oncology and co-director of the clinic. “It’s a quality-of-life issue.”

For some patients, improved surgical techniques or targeted radiation can result in a cure.

Clinical trials test new brain metastases treatments

Li and colleagues are conducting clinical trials to test new treatment approaches for multiple tumors.

One clinical trial compares whole-brain radiation to a combination of immunotherapy drugs and stereotactic radiosurgery, a type of highly focused radiation.

The immunotherapy trains the immune system to fight cancer, and the stereotactic radiosurgery targets tumors while sparing nearby healthy brain tissue. This combination has shown promising early results in disease control.

Other clinical trials have shown that some drugs are capable of penetrating the brain’s defenses to attack tumors.

And, says Li, “For some patients with one to three small brain metastases, improved surgical techniques or targeted radiation can result in a cure.”

It gives me confidence to know that my physicians are communicating and all on the same page.

Streamlined brain metastasis treatment

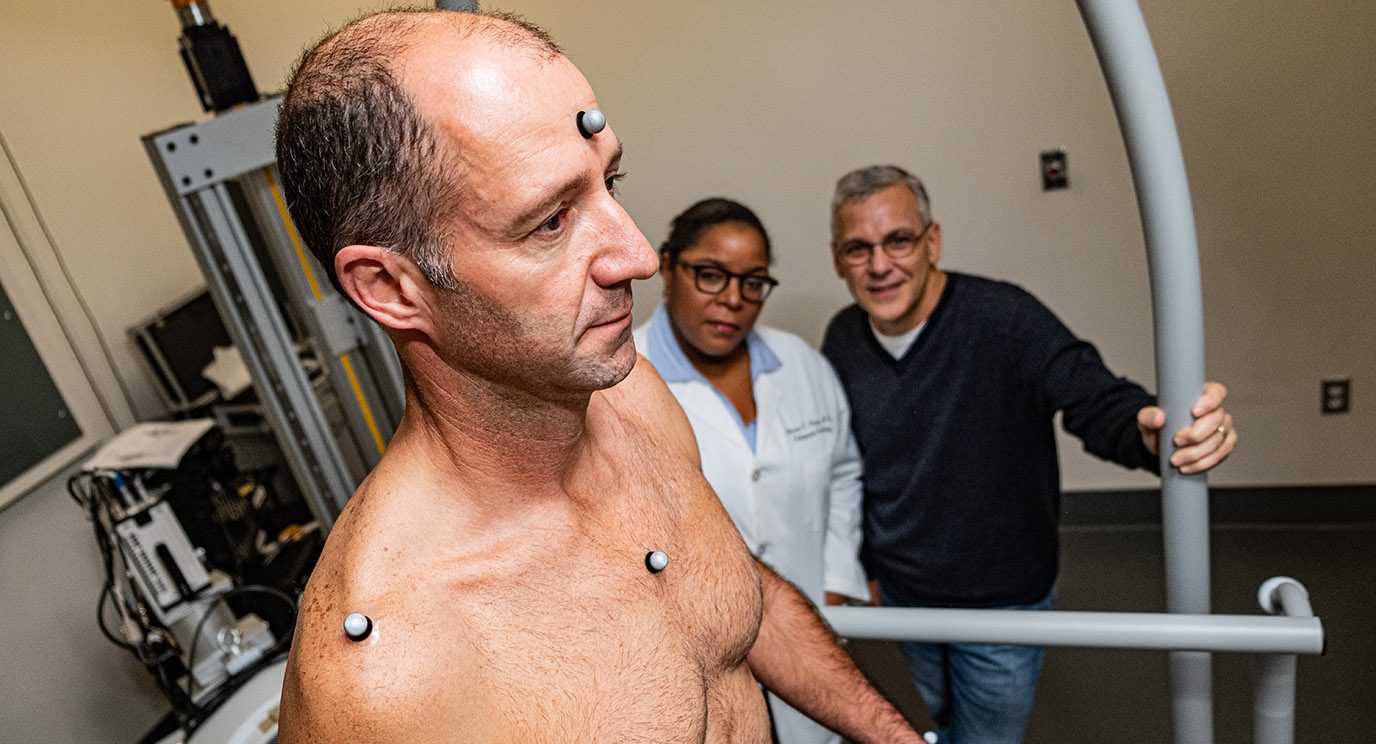

In a single visit at the clinic, patients see a team of health care specialists to develop a treatment plan. By sparing them multiple appointments that can stretch over days, the clinic paves the way for treatment to begin sooner.

“One of the goals for our clinic is to facilitate treatment faster,” says Hussein Tawbi, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of Melanoma Medical Oncology and co-director of the clinic. “The important thing is how quickly we’ve adopted this approach and how happy patients and families have been with it.”

Melanoma patient Gary Guthrie agrees. After having a single brain metastasis treated with radiation in California – in collaboration with MD Anderson oncologists – Guthrie visited the new clinic in October.

“My doctors were all in the same room at the same time during my appointment,” says Gary, a retired law enforcement officer who had just moved to Texas with his wife, Leslie. “It gives me confidence to know that my physicians are communicating and all on the same page.”

The tumor in Guthrie’s brain is withering away, and he’s now undergoing treatment for remaining metastases in other areas of his body.

This was a seminal moment in melanoma and in brain metastasis.

Changes to clinical trial exclusions for brain metastasis patients

Brain metastases, or secondary brain tumors, occur in 10% to 30% of adults with cancer. Historically, Tawbi notes, patients with multiple brain metastases have survived only three to six months after diagnosis.

These patients have commonly been excluded from clinical trials of new drugs. This is because the blood-brain barrier blocks most drugs from entering the brain, protecting tumors as well as brain tissue.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – the federal agency that approves new therapies – applies additional scrutiny to drugs that are capable of affecting the brain. The combination of a difficult target and additional regulation has steered drug companies toward developing anti-cancer drugs that avoid the brain.

“Twelve drugs have been approved for melanoma – 6,711 patients were treated in those trials, and not one with a brain metastasis got in because these drugs weren’t designed to enter the brain,” Tawbi says.

This began to change, initially by serendipity, during an international clinical trial of combination targeted therapies, which are drugs tailored to the genetic characteristics of a patient’s specific tumor. During the clinical trial, an Australian clinic found it had inadvertently treated a patient with a previously imaged brain metastasis. When they took new images, the tumor in the patient’s brain was gone.

The investigators persuaded the drug company to open a separate arm of the trial for patients with tumors in the brain. Of the 10 treated, nine saw their tumors shrink.

“This was a seminal moment in melanoma and in brain metastasis,” Tawbi says.

A follow-up trial led by Michael Davies, M.D., Ph.D., chair of Melanoma Medical Oncology, showed that brain tumors shrank in 58% of stage IV melanoma patients with a specific mutation in their tumors, when treated with the targeted therapy combination. The tumors began to grow again after six to seven months, but the clinical trial showed that small-molecule drugs could indeed reach tumors in the brain.

Tawbi subsequently led a clinical trial of two drugs that, when used together, train the immune system to attack cancer. Tumors shrank in 56% of patients in the trial; they disappeared altogether in another 26%. Nine months later, tumors still had not progressed in 59% of patients enrolled in the study.

What’s ahead for treating brain metastases

These and other clinical trials have persuaded some pharmaceutical companies to begin designing drugs against brain metastases, and the FDA has indicated it will require an explanation for excluding these patients from clinical trials.

Fourteen open clinical trials are associated with MD Anderson’s Brain Metastases Clinic. Together, they’re testing a variety of drugs in combination with other therapies. For now, these clinical trials focus on specific cancer types – breast cancer or melanoma, for example.

But soon, Tawbi says, the clinic hopes to offer clinical trials that will be open to all patients with brain metastases, regardless of where their primary tumor started.

Request an appointment at MD Anderson online or by calling 1-877-632-6789.