In 2015, surgical history was made

Collaboration and a unique opportunity led to the world’s first skull and scalp transplant

After undergoing a first-of-its-kind surgery, music lover Jim Boysen is back home in Austin, doing the things he loves.

“I’m playing keyboards, riding my mountain bike and enjoying my favorite Tex-Mex foods,” says the 56-year-old software engineer, who’s also back at work and “feeling great.”

“That pre-surgical diet was bland and boring. Give me enchiladas any day.”

Last May, doctors from MD Anderson and Houston Methodist Hospital performed the world’s first skull and scalp transplant on Boysen, whose treatment for a rare cancer of the scalp muscle left him with a deep head wound.

During the same surgery, he also received a kidney and pancreas transplant, making it the first time a patient has undergone a simultaneous craniofacial and solid-organ transplant.

Boysen’s first kidney-pancreas transplant was in 1992, a result of diabetes he’s had since he was 5 years old. The immune suppression drugs he took to keep his body from rejecting his kidney and pancreas raised the risk of cancer and he developed leiomyosarcoma, a rare type of cancer affecting the smooth muscle under his scalp.

The drugs also prevented his body from repairing the wound caused by radiation therapy for his scalp cancer. To make matters worse, the transplanted organs he received 23 years ago were starting to fail.

However, doctors couldn’t perform a new transplant as long as he had an open scalp wound.

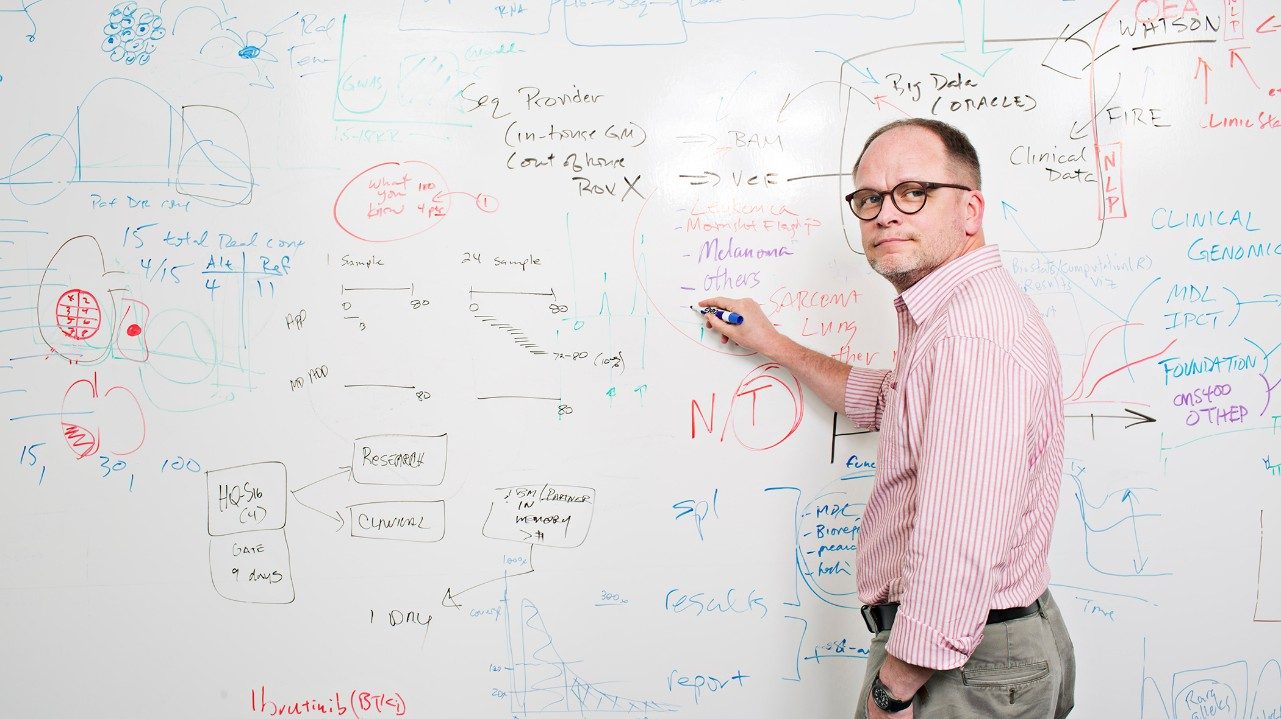

Jesse Selber, M.D., a reconstructive plastic surgeon at MD Anderson, saw a unique opportunity after first meeting Boysen several years ago. His solution was to give Boysen a partial skull and scalp, a pancreas and a kidney, all at once.

“Opportunity favors the prepared mind,” Selber says. “I’ve been deeply interested in composite tissue transplant since I was in surgical training. I read immunology textbooks and got up to date on this state-of-the-art procedure, which is a kind of subset of reconstructive microsurgery.”

From opportunity to orchestration of a world first

In composite tissue transplantation, doctors transfer skin, muscle, bone and nerve from a donor to a recipient. It’s less established than solid-organ transplants and free-flap procedures that use tissue harvested from the patient’s own body.

Fortunately for Boysen, MD Anderson has one of the most recognized microsurgery programs in the world.

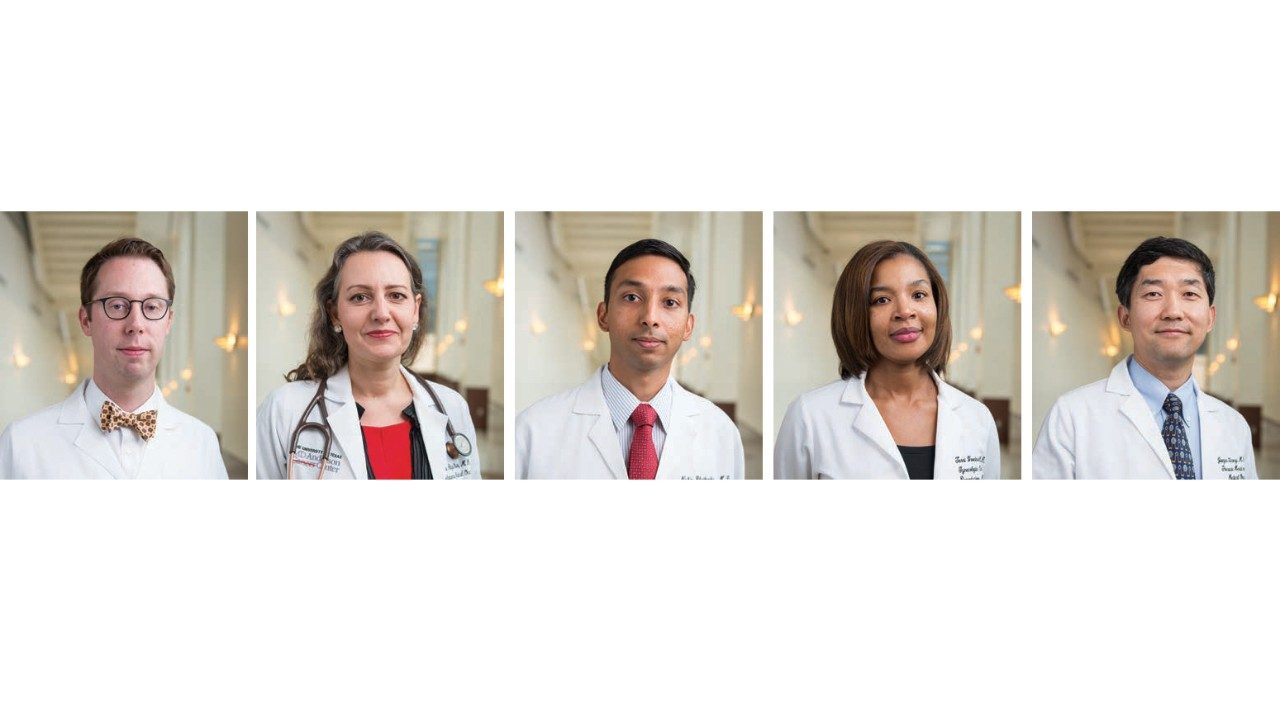

Selber led Boysen’s microsurgery team, which included professors Matthew Hanasono, M.D. and Peirong Yu, M.D., and assistant professors Edward Chang, M.D. and Mark Clemens, M.D.

“While the approach seemed radical at first, in practice, we perform these techniques every day,” says Clemens. “By using them for Mr. Boysen, we helped him and, in the process, broke through certain surgical dogma and opened up a new reconstruction option for our cancer patients.”

The moment Clemens cherishes most is when blood flowed to Boysen’s scalp following hours of delicate surgery to connect blood vessels about half the diameter of a human hair.

“A blush of pink spread across the skin in a wave,” he recalls. “The surgery itself is very mechanical. But seeing that suddenly reminds you of the magnitude at hand and the stunning realization that it is possible.”

Chang, who performs more than 100 free-flap procedures a year, felt the enormity of this procedure resting on his shoulders.

“Every stitch I made seemed like a small step toward success, and even a little stumble or falter would mean failure.”

In the end, the successful procedure, which involved a team of about a dozen doctors and 40 health care professionals, created a gateway to more composite tissue transfers in the future.

“It certainly opens a lot of doors for patients who take immunosuppressive medications for organ transplants to undergo transplant of skin, muscle and skeletal structures as well,” Hanasono says.

Yu agrees.

“The experience really shows that by working together we can help many patients who need sophisticated multiple-organ transplantation.”