Outsmarting cancer with genetic testing

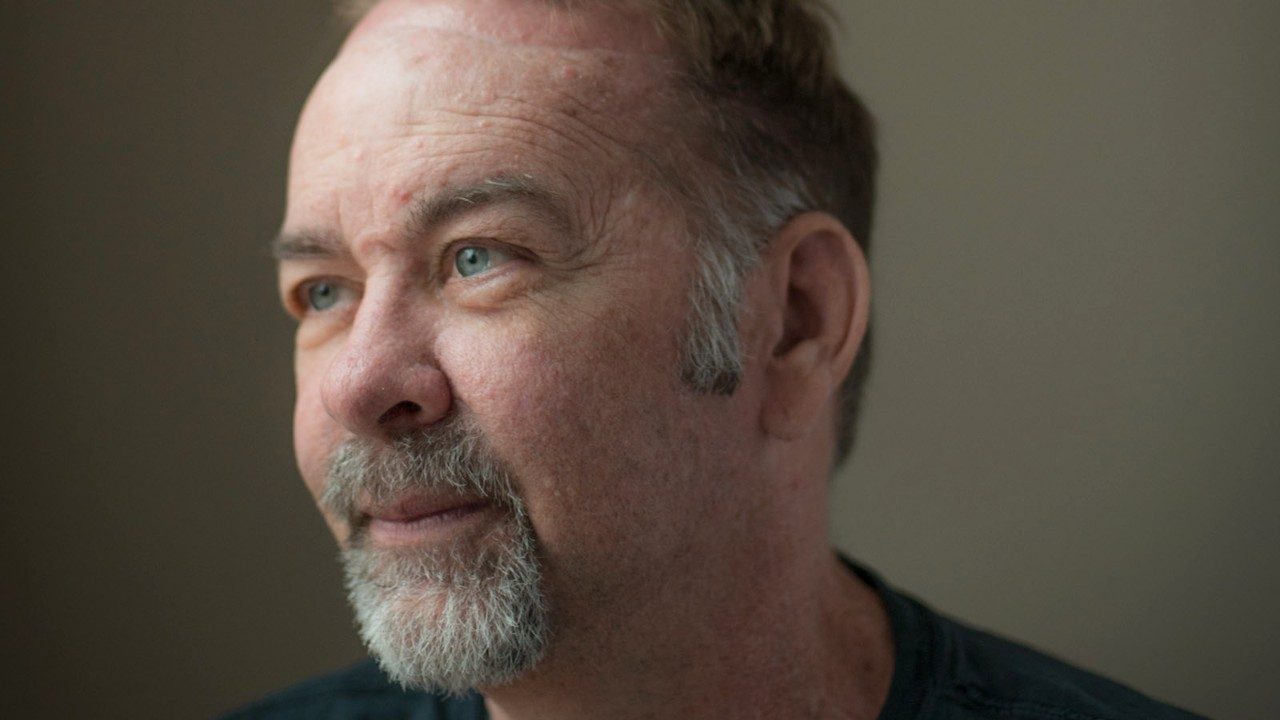

Teresa Hall’s visit to a gastroenterologist three years ago wasn’t the first time she’d sought help for troubling symptoms.

Over the span of a decade, she’d consulted three other doctors, and all had diagnosed her with irritable bowel syndrome. But the gastroenterologist told her otherwise.

At age 32, Hall learned her colon and rectum were riddled with polyps. Two were cancerous.

“All three of those doctors missed it. They never once said, ‘You know, maybe we need to do a colonoscopy on this girl,’” says Hall, despite the fact she shared her alarming family history with each doctor.

She told them about how her father’s colon and rectum were removed when he was 36 because of thousands of pre-cancerous polyps.

“If I’d had a colonoscopy, my cancer would’ve been caught very early. It probably wouldn’t even have been cancer at that point.”

Like her father, Hall had her entire colon and rectum removed, and she underwent chemotherapy. When doctors discovered the cancer had spread to her liver and lungs, she sought help from MD Anderson. After more rounds of chemo and several surgeries, she’s hanging tough.

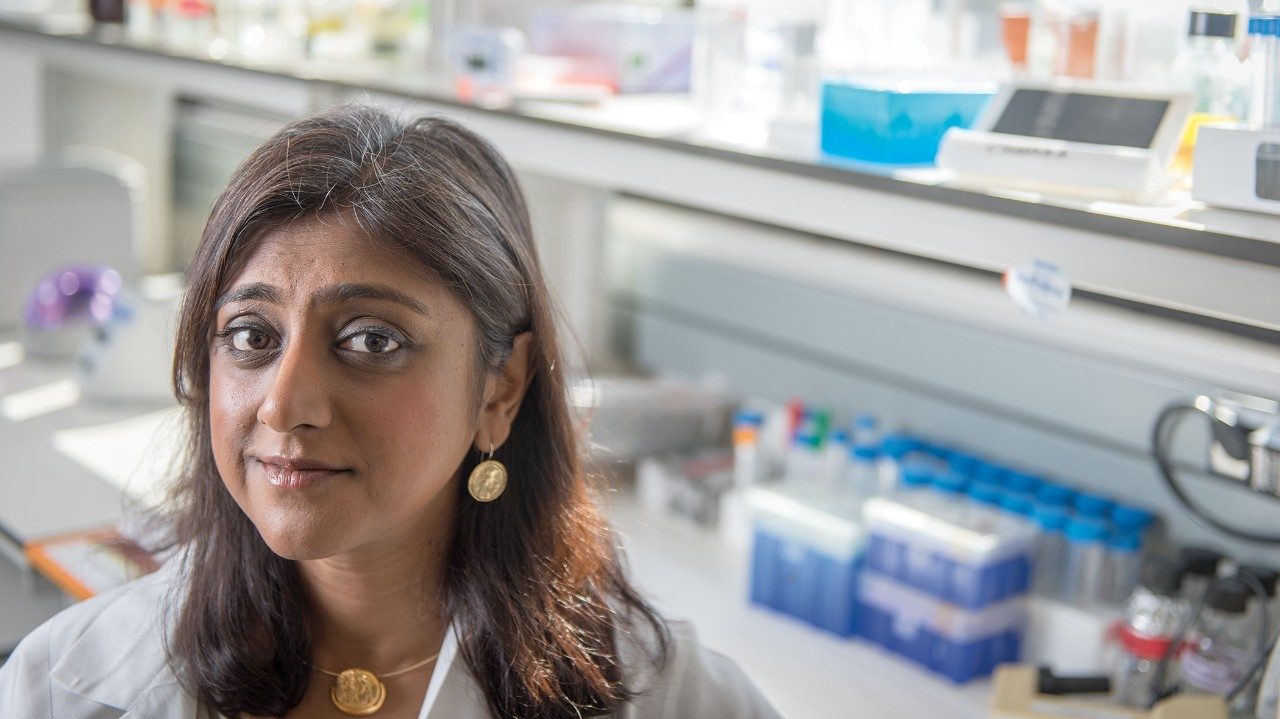

Because of her young age and family history, Hall underwent genetic testing at MD Anderson. The test revealed she had a hereditary cancer syndrome known as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

The lifetime risk of colorectal cancer for most people is 5%. For those with hereditary syndromes such as FAP or Lynch syndrome, it’s much higher. Lynch syndrome carries a lifetime cancer risk of 50 to 80%, and those with FAP have a 100% chance of developing cancer without treatment.

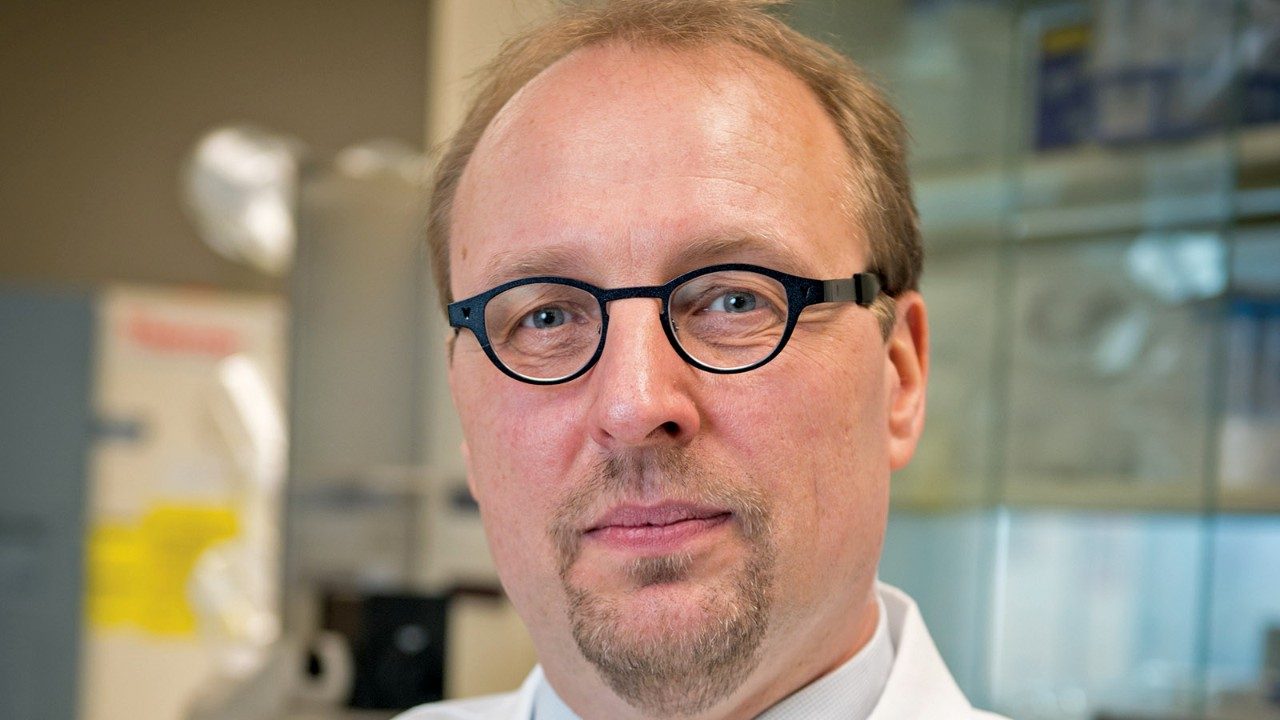

Although only about 5% of colorectal cancer is caused by hereditary syndromes, the incidence tends to be higher in those diagnosed at a younger age. To learn more about hereditary syndromes in adolescents and young adults, MD Anderson researchers studied nearly 200 colorectal cancer patients diagnosed at age 35 or younger. All were evaluated by the institution’s genetic counselors.

The study found that one-third of patients diagnosed before age 35 had hereditary-associated cancer.

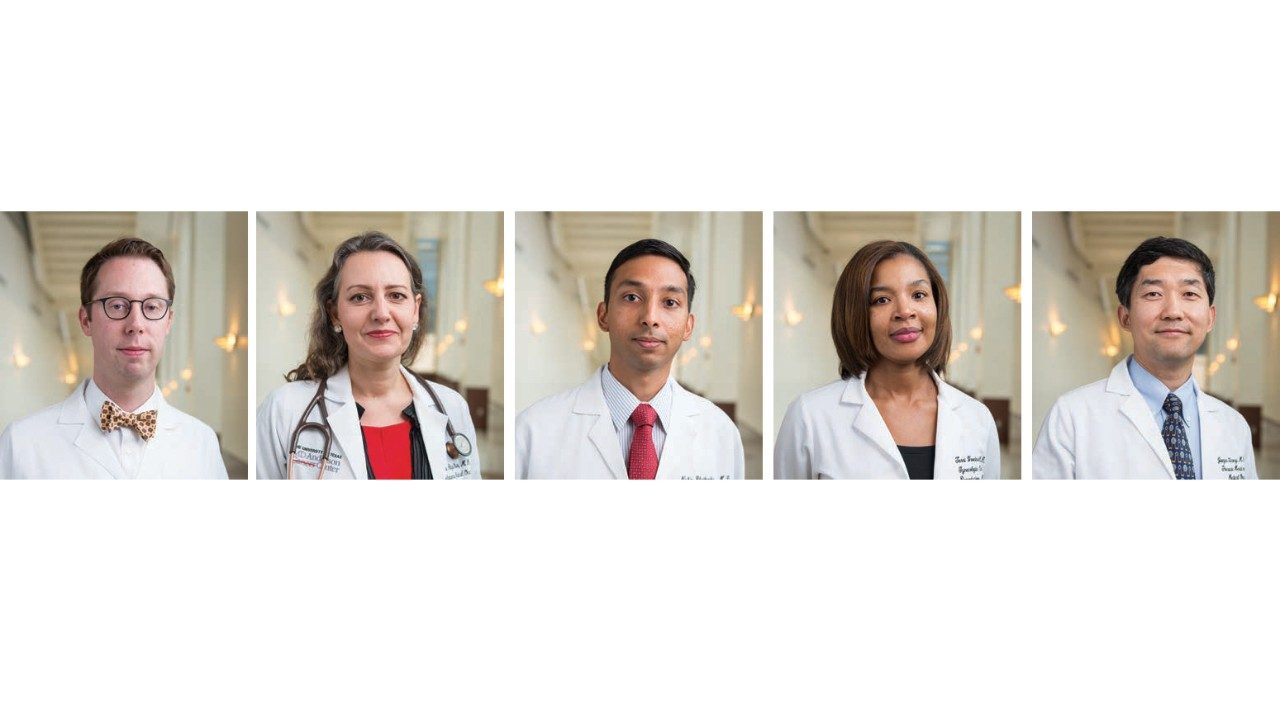

“Based on our findings, patients younger than 35 must be evaluated by a genetic counselor,” says Eduardo Vilar- Sanchez, M.D., Ph.D., the study’s principal investigator. “They’re encouraged to share their genetic risk with their parents, siblings and other relatives, who can also get tested.”

Testing can identify relatives with high-risk mutations and allow them to take preventive measures, such as earlier screenings, explains Vilar-Sanchez, an assistant professor of Clinical Cancer Prevention.

Other than her father, Hall’s family history contains no colorectal conditions of any kind. However, her family members are now being tested.

Hall’s son doesn’t appear to have the mutation, and her daughter is still too young for testing. Her sister and nephew, however, both carry the harmful FAP mutation. Hall’s sister had her colon and rectum removed to reduce her cancer risk. Hall’s nephew is watched closely and may enter clinical trials when he’s old enough.

“My advice is, if you have symptoms, be an advocate for yourself, regardless of how embarrassing it can be,” says Hall. “Get a colonoscopy. If one doctor won’t do it, find another doctor. Getting tested saves lives. It really does.”

If you think you might be at risk for an inherited cancer, it’s a good idea to meet with a genetics counselor. They will review your family medical history, talk to you about the role of genetics in cancer and perform a hereditary cancer risk assessment.

Based on your results, the counselor may recommend genetic testing, which simply involves having a blood sample drawn. The findings may help determine if members of your family face higher risks for certain types of cancer.