When good genetic mutation goes bad

Generally speaking, hypermutation and DNA damage in a cell are bad things. That is, unless you’re talking about an immune system B cell.

B cells craft antibodies to precisely fit onto antigens — targets on invading viruses, bacteria or defective cells that the adaptive immune system wants to destroy.

In that case, massive mutations, DNA strand breaks and recombination help B cells mix and match characteristics necessary to generate the perfect antibody.

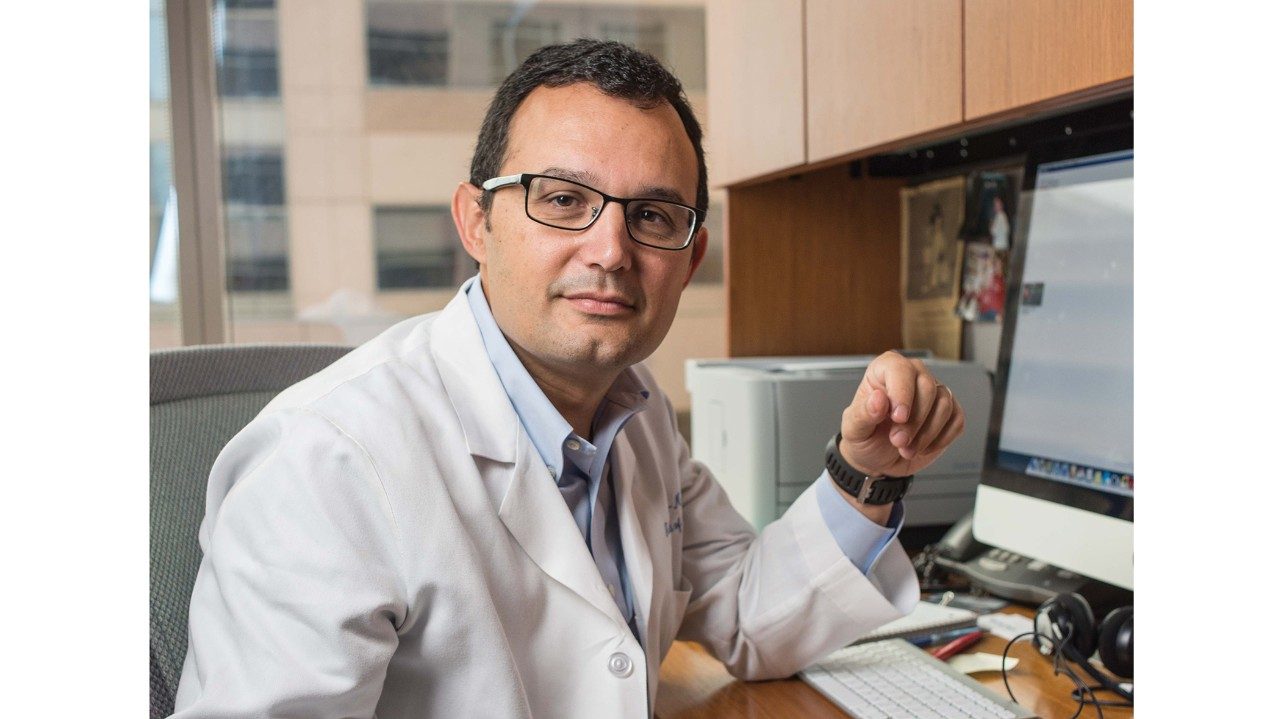

“Everything you want to prevent in cancer, B cells do,” says Kevin McBride, Ph.D., assistant professor in Molecular Carcinogenesis. “So this process usually is very tightly controlled.”

It’s also necessary. All vaccines work by generating antibodies that fit into the target like a key in a lock. Each B cell makes a completely different antibody, and the immune system can make “quadrillions of types of antibodies,” McBride points out.

Problems occur when massive genetic mutations and DNA damage veer off course and impact genes that regulate cell growth and function. The result: B cell leukemias and lymphomas.

McBride’s research at the Virginia Harris Cockrell Cancer Research Center at MD Anderson’s Science Park in Smithville, Texas, focuses on the molecular processes used by B cells to make antibodies.

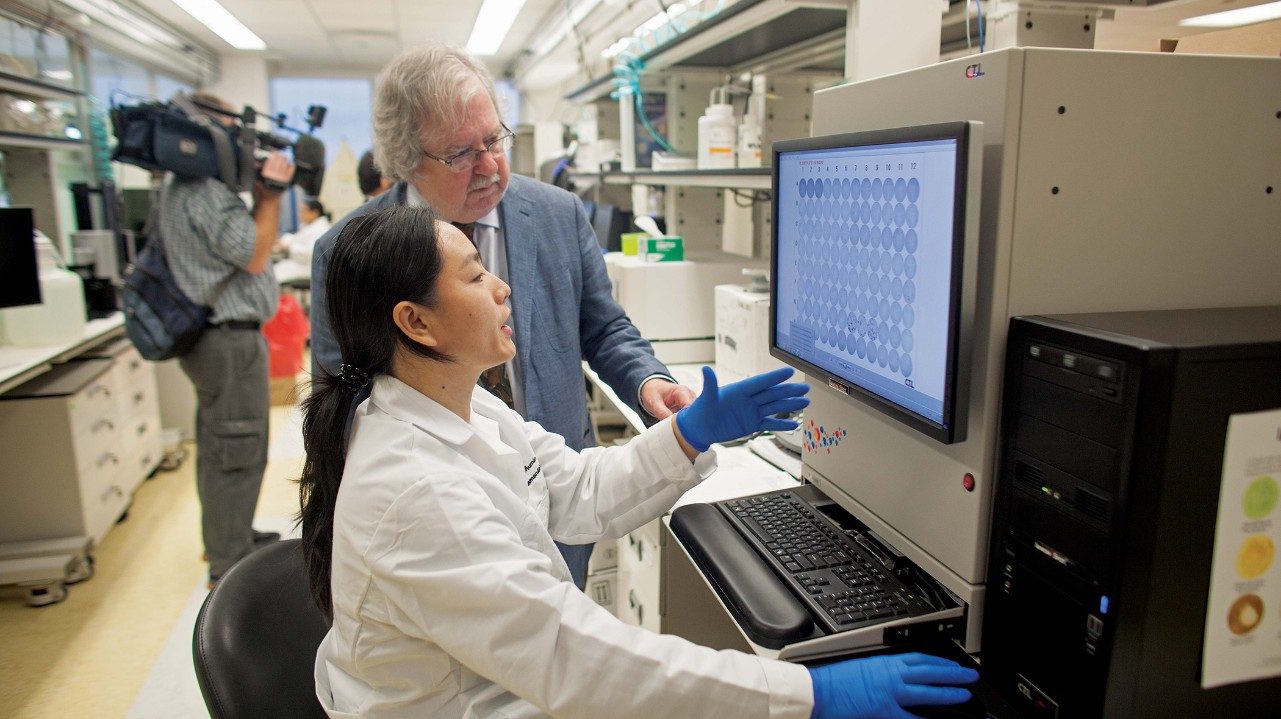

In particular, his team studies activation-induced deaminase (AID), an enzyme that launches hypermutation and double-strand breaks, usually in a beneficial manner.

“The vast majority of lymphomas occur in B cells that have gone through the process in which they express AID,” McBride says.

By understanding the basic science, McBride and colleagues are illuminating both proper immune system function and the path to B cell malignancies.

“Everything you want to prevent in cancer, B cells do.”