Improving odds by making cancer more predictable

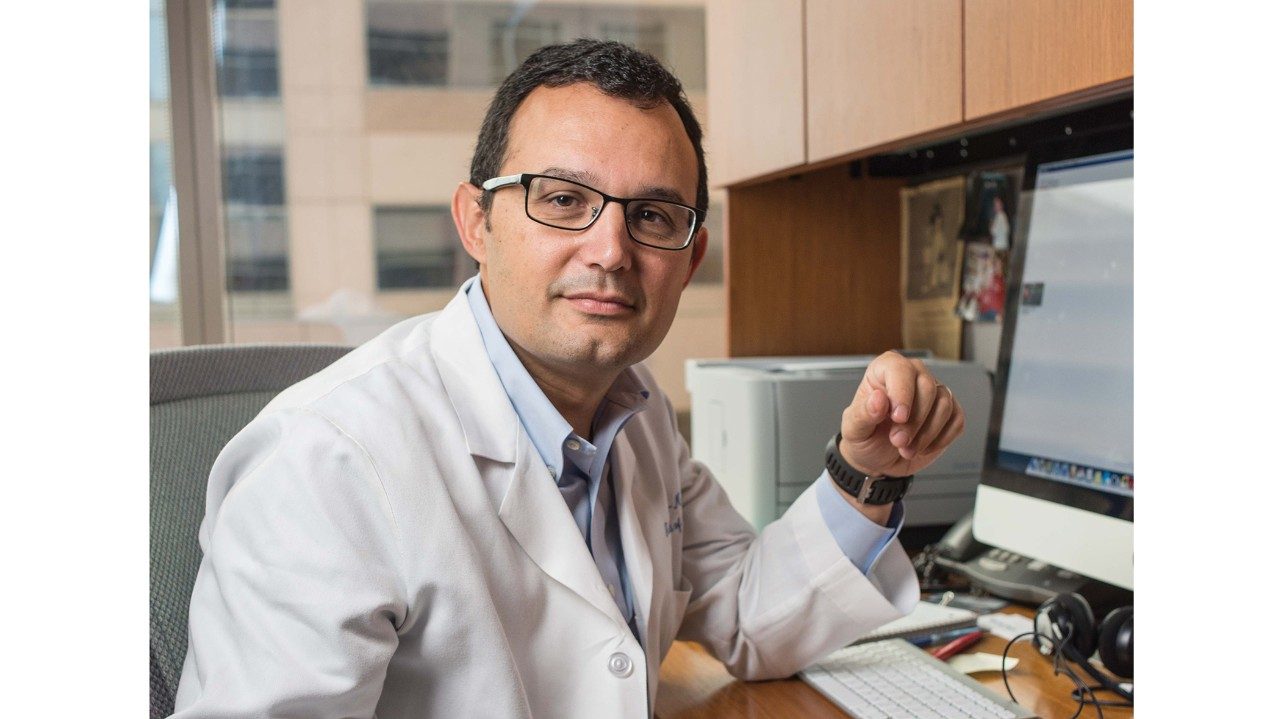

Paul Scheet, Ph.D., has a background in population genetics, which makes his role in the cancer prevention process a unique and important one.

“Explaining to mingling wedding guests what you do for a living can be challenging. I usually just say ‘genetics’ and then gauge from their reaction how far I can take it,” jokes Paul Scheet, Ph.D., associate professor in Epidemiology at MD Anderson.

Scheet’s role in the cancer prevention process is a unique and important one. His background in population genetics led to his current research: developing new statistical methods that clinicians and geneticists can use to profile tumors and, ultimately, evaluate cancer risk.

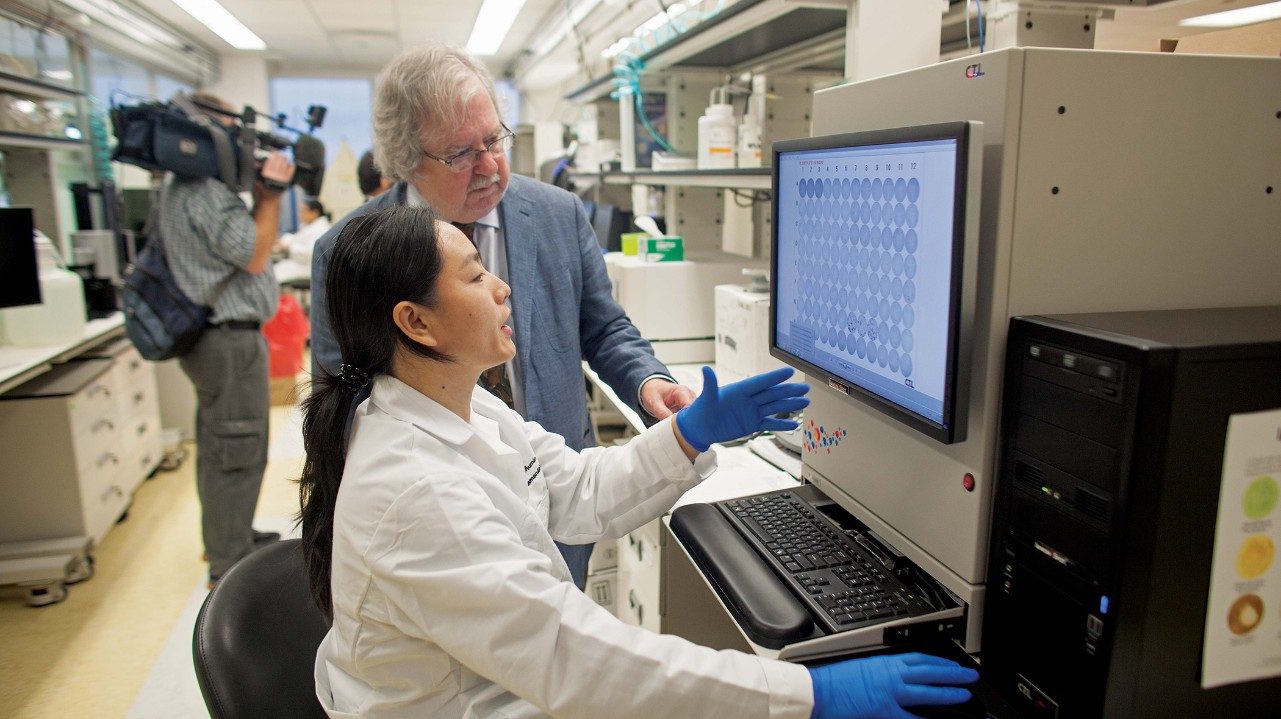

Under normal circumstances, when a cell divides, an identical copy of its DNA is created. However, mistakes — known as mutations — may occur during this copying process. Mutations can accumulate with age and exposure to certain environmental factors such as ultraviolet (UV) radiation. A mutation such as a deletion of a portion of a chromosome can turn off a tumor-suppressing gene in a cell, increasing cancer risk.

“Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) — for example, from deletions — is difficult to measure when it exists in a small portion of the cells because standard technologies survey the entire heterogeneous mixture of cells,” Scheet says. “To increase our ability to detect LOH, we incorporate knowledge of a person’s two inherited chromosomes to inform specific patterns expected from losing part of one of them.”

Scheet says studies show that genetic mosaicism (different forms of the genome in one person) may predict cancer risk. Think of it as a warning signal. The earlier the warning, the fewer mutations. Therefore the signal is very weak. Scheet’s goal is to provide statistical methods that pick up the weaker signals.

Scheet is collaborating with Kenneth Tsai, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor in Dermatology and Immunology, to identify early genetic changes in skin exposed to UV radiation as a way to quantify a person’s risk for developing cancer. His seed-funding award comes from the Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment.

“Sun-induced changes in the DNA of otherwise normal skin may predict whether a person develops skin cancer,” Scheet says. “If true, this may suggest a relatively simple test with which a clinician could personalize prevention strategies such as surgery and screening.”

Genetic mutations can accumulate with age and exposure to certain environmental factors such as ultraviolet radiation.

Protect your skin and reduce your risk

Your sunscreen should:

- Protect against both UVA and UVB rays

- Have a sun protection factor (SPF) of at least 30

- Be applied 30 minutes before going outdoors

- Be reapplied every 1-2 hours

- Be reapplied after swimming, sweating or towel drying

Don’t forget:

- Use a lip balm that’s SPF 30 or higher

- Cover as much skin as possible with hats and clothing

- Stay in the shade