AML and MDS Moon Shot Annual Report 2013

Triumph after a trial and tribulations

When Mary Cates was told she had cancer, she didn’t flinch . . . either time.

“I told my doctor, `You better not lie to me.’”

That was in 1969, when her physician informed her she had uterine cancer, her first bout with the disease. She fully recovered after a complete hysterectomy.

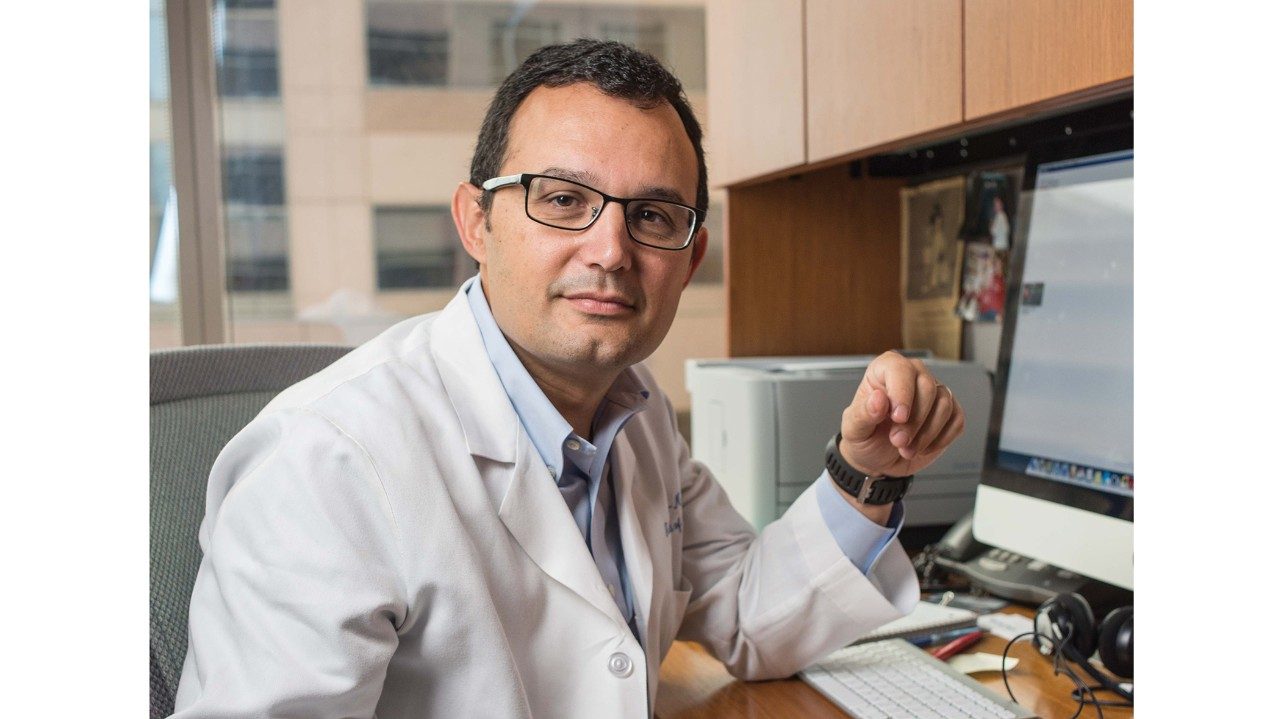

She faced the news again in 2011 when Guillermo Garcia-Manero, M.D., professor in Leukemia, told her she had acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

“I told Dr. Garcia-Manero the same thing,” says the 81-year-old Cates, referring to her demand for directness. “They don’t sugarcoat anything. That’s the way I want it to be.”

Garcia-Manero was honest. He informed Cates that the survival rate for someone her age was very, very low.

“I told him, ‘I’m not going to die.'"

Cates, who lives in Converse, La., a tiny town 55 miles south of Shreveport on the Louisiana/Texas border, never felt any of the symptoms related to AML. She wasn’t fatigued or anemic. “I never felt bad,” she says.

But in 2010, tests showed her white blood count was low. She visited an oncologist in Lake Charles, La., who diagnosed her with “pre-leukemia,” now known as myelodysplastic syndrome. A year of chemotherapy later, her condition was “not any better, not any worse.”

At that point, Cates, who describes herself as a woman who can’t sit down and do nothing, decided to come to MD Anderson for a second opinion.

Here, Garcia-Manero discovered she had a mutation of the FLT3 gene that was causing her body to produce blast cells — immature cells that don’t develop into mature white blood cells. He placed her in a clinical trial for sorafenib, an inhibitor that “turns FLT3 off,” allowing healthy cells to produce.

“They gave me powerful cancer pills,” Cates recalls. “They nearly killed me… but they saved my life.”

Cates was taking four pills a day. Her weight dwindled from 116 pounds to just 78. Over time her dose was decreased, and now she only takes one pill every other day, and the pills no longer make her sick. She also began chemotherapy seven days every month, a regimen that remains unchanged.

It hasn’t been easy, but Cates credits being alive to her optimism, her doctor and her faith.

“I thank God for giving him the ability to know what was wrong,” she says.

“The pills, the prayer and Dr. Garcia-Manero are what have brought me through.”

Mary Cates credits being alive to her optimism, her doctor and her faith.