- Diseases

- Acoustic Neuroma (14)

- Adrenal Gland Tumor (24)

- Anal Cancer (66)

- Anemia (2)

- Appendix Cancer (16)

- Bile Duct Cancer (28)

- Bladder Cancer (68)

- Brain Metastases (28)

- Brain Tumor (228)

- Breast Cancer (708)

- Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (2)

- Cancer of Unknown Primary (4)

- Carcinoid Tumor (8)

- Cervical Cancer (154)

- Colon Cancer (164)

- Colorectal Cancer (108)

- Endocrine Tumor (4)

- Esophageal Cancer (42)

- Eye Cancer (36)

- Fallopian Tube Cancer (6)

- Germ Cell Tumor (4)

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (2)

- Head and Neck Cancer (4)

- Kidney Cancer (124)

- Leukemia (344)

- Liver Cancer (50)

- Lung Cancer (286)

- Lymphoma (284)

- Mesothelioma (14)

- Metastasis (30)

- Multiple Myeloma (98)

- Myelodysplastic Syndrome (60)

- Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (4)

- Neuroendocrine Tumors (16)

- Oral Cancer (98)

- Ovarian Cancer (172)

- Pancreatic Cancer (168)

- Parathyroid Disease (2)

- Penile Cancer (14)

- Pituitary Tumor (6)

- Prostate Cancer (144)

- Rectal Cancer (58)

- Renal Medullary Carcinoma (6)

- Salivary Gland Cancer (14)

- Sarcoma (234)

- Skin Cancer (294)

- Skull Base Tumors (54)

- Spinal Tumor (12)

- Stomach Cancer (60)

- Testicular Cancer (28)

- Throat Cancer (90)

- Thymoma (6)

- Thyroid Cancer (98)

- Tonsil Cancer (30)

- Uterine Cancer (78)

- Vaginal Cancer (14)

- Vulvar Cancer (18)

- Cancer Topic

- Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Issues (20)

- Advance Care Planning (8)

- Biostatistics (2)

- Blood Donation (18)

- Bone Health (8)

- COVID-19 (362)

- Cancer Recurrence (120)

- Childhood Cancer Issues (120)

- Clinical Trials (622)

- Complementary Integrative Medicine (22)

- Cytogenetics (2)

- DNA Methylation (4)

- Diagnosis (222)

- Epigenetics (6)

- Fertility (62)

- Follow-up Guidelines (2)

- Health Disparities (14)

- Hereditary Cancer Syndromes (122)

- Immunology (18)

- Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (8)

- Mental Health (116)

- Molecular Diagnostics (8)

- Pain Management (64)

- Palliative Care (8)

- Pathology (10)

- Physical Therapy (18)

- Pregnancy (18)

- Prevention (872)

- Research (386)

- Second Opinion (74)

- Sexuality (16)

- Side Effects (596)

- Sleep Disorders (10)

- Stem Cell Transplantation Cellular Therapy (216)

- Support (402)

- Survivorship (324)

- Symptoms (180)

- Treatment (1760)

How does targeted therapy treat cancer?

5 minute read | Published June 07, 2024

Medically Reviewed | Last reviewed by an MD Anderson Cancer Center medical professional on June 07, 2024

Each cancer patient is unique. So, when developing a cancer treatment plan, our doctors consider all the things that make them that way, including their diagnosis, medical history and treatment preferences. Targeted therapy enables us to personalize cancer treatment even further by tailoring drugs to the genetic characteristics of a patient’s specific tumor.

“Unlike traditional chemotherapy, targeted therapy focuses on specific molecules that are thought to be important for cancer cell growth,” says Ecaterina Dumbrava, M.D., who specializes in Investigational Cancer Therapeutics.

Sometimes referred to as "precision medicine" or "personalized medicine," targeted therapy aims to stop or slow down the growth of cancer. Targeted therapy drugs are given either as a pill or through an IV.

How targeted therapy personalizes cancer treatment

Cancer develops when a normal cell’s genes change, causing it to divide quickly and then multiply out of control. The change in a cell’s genes is called a mutation. Only about 5% to 10% of cancers are caused by inherited genetic mutations passed down from parent to child (such as BRCA1 and BRCA2). Most are due to risk factors such as age, sun damage, tobacco use, and other unknown causes.

No matter how a mutation forms, though, targeted therapy works the same. But it's different from traditional chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy kills all cells that multiply quickly, regardless of whether they’re cancerous. Targeted therapy, meanwhile, is designed to find and slow down the growth of cells that have a particular mutation. The mutation is identified through next-generation sequencing. This is a process in which we take a small tissue sample from the tumor and then analyze it in a lab.

“Genetic testing is now recommended for anyone with pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, ovarian cancer and breast cancer,” notes Dumbrava. “These cancers are known to have a higher percentage of hereditary components. So, testing is important not just for your extended family’s sake, but also because there might be precisely matched treatment options available for you.”

Targeted therapy side effects

Because targeted therapies attack only cancer cells, some patients experience fewer side effects than they would with traditional chemotherapy. Depending on the type of targeted therapy you receive, your side effects might include:

- diarrhea

- skin changes, such as itchiness, rash or changes in pigmentation

- bleeding problems, including clotting or high blood pressure.

“Think of your body as a garden and cancer as a weed,” suggests Dumbrava. “Sometimes, cancer has certain characteristics that allow a highly specialized weed killer to target those weeds without harming the flowers around them.”

Phase I clinical trials make targeted therapy available to more patients

Targeted therapy is not for everyone. Not every patient’s tumor carries a genetic mutation that’s been identified as cancer-causing or having a potential targeted therapy option. And, just like chemotherapy, it’s not guaranteed to work in all patients.

Currently, targeted therapies approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Association (FDA) are available for patients with mutations/alterations in the following genes:

These mutations have been linked to breast cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, melanoma, and several others.

Other genetic markers that can predict response to immunotherapy include:

- Microsatellite Instability-High (MSI-H): This indicates that a tumor has a lot of genetic changes, making it more visible to the immune system. We often test for MSI-H in colorectal and endometrial cancers.

- Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB): A high TMB means a tumor has many mutations, which can make the cancer cells easier for the immune system to recognize and attack. This test can be useful for multiple types of cancer.

- Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1): This protein can be found on the surface of cancer cells, and it helps them hide from the immune system. Testing for this can be helpful in determining if immunotherapy might work.

But researchers are constantly striving to identify and understand the function of more cancer-causing genes, so they can develop new targeted therapies for them through Phase I clinical trials. The goal is to build on the successes of existing targeted therapies by combining them with other targeted therapies, as well as other treatments like chemotherapy, immunotherapy and radiation therapy.

“All of our clinical trial choices are based on a strong biological rationale, which matches a tumor’s characteristics with a specific drug,” adds Dumbrava. “We don’t always know if something is going to work, but we make decisions based on what we do know and then find a matched treatment based on that. Phase I clinical trials allow us to identify the right doses, the best schedules, and any potential side effects.”

Historic advances and what’s on the horizon for targeted therapy

MD Anderson clinical trials have already led to the approval of targeted therapies for several rare diseases, including the first-ever FDA-approved treatment for BRAF V600E mutation-positive anaplastic thyroid cancer. The combination of the targeted therapies dabrafenib and trametinib was subsequently approved for use against any cancer with a BRAF V600E mutation.

The drug selpercatinib, meanwhile, has been approved to treat any cancer driven by a RET fusion, including medullary and papillary thyroid cancers, non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer and bile duct cancer, all of which have historically been difficult to treat.

In addition, research led by David Hong, M.D., and Ferdinandos Skoulidis, M.D., Ph.D., found the drug sotorasib effectively treats lung cancer with the KRAS G12C mutation.

“Until recently, KRAS was not even considered a good target for matched targeted therapies,” notes Dumbrava. “This shows just how fast targeted therapies are evolving. Hopefully, other genes will soon follow, such as TP53, which is known as the ‘guardian of the genome.’”

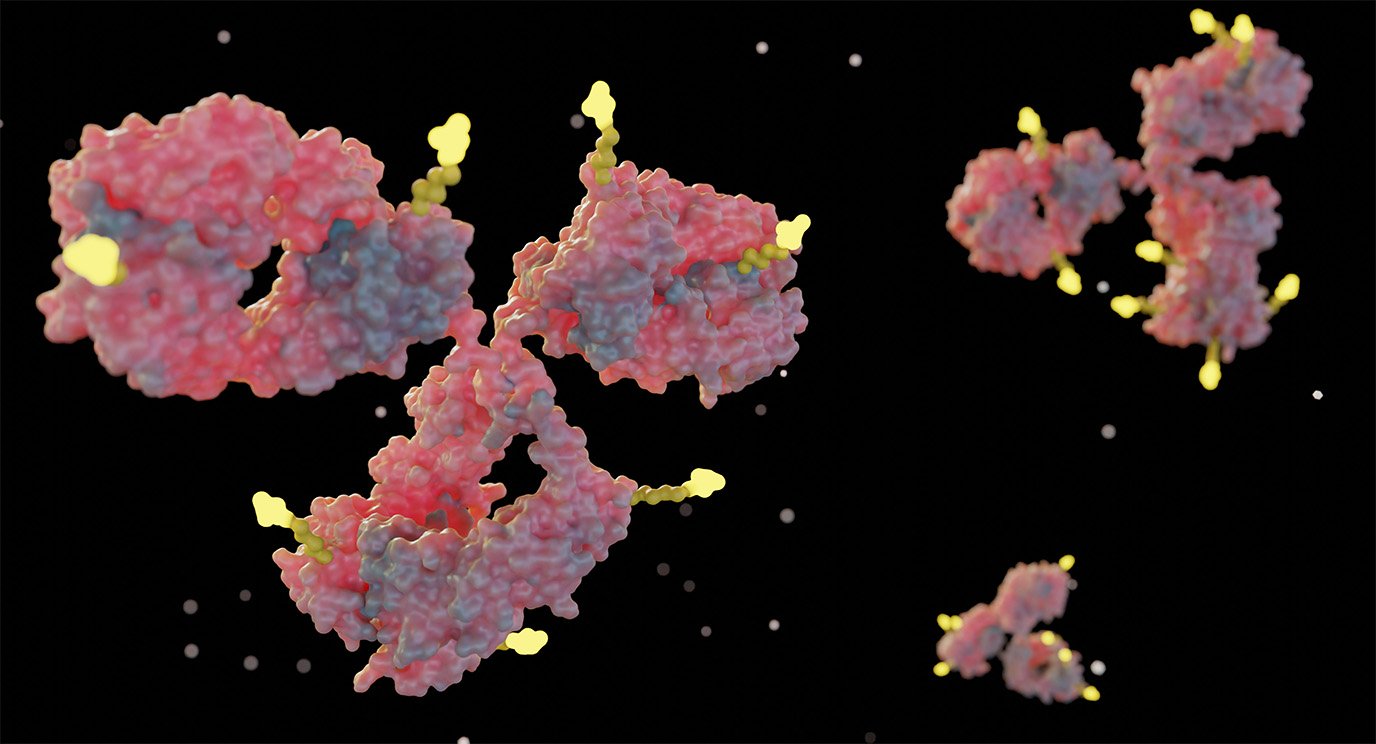

The next big thing in targeted therapy is antibody drug conjugates. These enable antibodies targeting specific proteins on a tumor cell to carry chemotherapy and deliver it directly to the cancer.

“It’s almost like a Trojan horse,” explains Dumbrava. “The chemotherapy drug is not even activated until it connects with the appropriate marker on the cancer cell.”

And, research led by Funda Meric Bernstam, M.D., has already resulted in FDA approval of the antibody drug conjugate trastuzumab deruxtecan for any solid tumors that have high HER2 expression.

Targeted therapy clinical trials give some patients more time

With some widely-used FDA-approved cancer treatments like chemotherapy, only a small number of patients see a response. But personalized cancer therapy offers experimental options designed to target the unique characteristics of an individual’s cancer — sometimes with impressive results.

“Targeted therapies can significantly improve outcomes, prolong survival, and help maintain a good quality of life,” notes Dumbrava. “Some of our patients were faced with a choice between hospice care and a clinical trial, and we’ve been treating them successfully for years.”

Request an appointment at MD Anderson online or call 1-888-523-1473.

Targeted therapies can significantly improve outcomes, prolong survival, and help maintain a good quality of life.

Ecaterina Dumbrava, M.D.

Physician & Researcher