Is seed oil healthy?

There have been mixed messages about whether seed oils are healthy or unhealthy. On one hand, seed oils are unsaturated, or “healthy” fats. But you may have also heard that seed oil is linked to inflammation or isn’t safe to consume. Confusing, right?

While you may want to categorize seed oils as either good or bad, Senior Clinical Dietitian Joy Anderson stresses the importance of how you consume seed oil.

Is seed oil healthy?

Medication disposal: How to get rid of unused or expired medicine

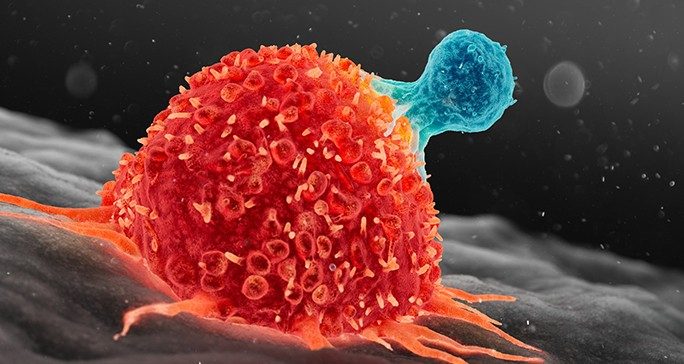

Invasive ductal carcinoma: 6 things to know about this common breast cancer

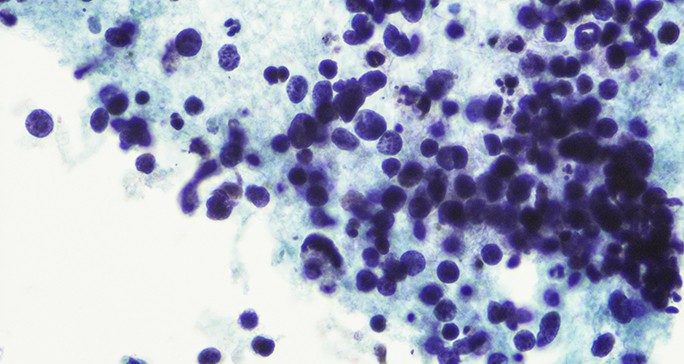

What can a pathology report tell you?

Gynecologic oncologist: Why I’m passionate about cancer care at MD Anderson

|

$entity1.articleCategory

|

|---|

|

$entity2.articleCategory

|

|

$entity3.articleCategory

|

|

$entity4.articleCategory

|

|

$entity5.articleCategory

|

|

$entity6.articleCategory

|

Find stories by topic

Find out everything you need to know to navigate a cancer diagnosis and treatment from MD Anderson’s experts.

What can a pathology report tell you?

April 10, 2025

What are the symptoms of liposarcoma?

April 08, 2025

Cancer treatment side effect: Muscle cramps

April 03, 2025

Read inspiring stories from patients and caregivers – and get their advice to help you or a loved one through cancer.

Music to a mother’s ears: Awake craniotomies bring musicians together

February 24, 2025

Art Space volunteer draws inspiration from young friend

January 31, 2025

Get MD Anderson experts’ advice to help you stay healthy and reduce your risk of diseases like cancer.

Is seed oil healthy?

April 14, 2025

Diet soda and cancer risk: What you should know

April 09, 2025

How to get your heart rate up

April 04, 2025

What happens when you overeat?

April 01, 2025

How to make colonoscopy prep better

March 31, 2025

Negative effects of vaping on teens

March 28, 2025

Learn how MD Anderson researchers are advancing our understanding and treatment of cancer – and get to know the scientists behind this research.

How non-scientists are helping cancer researchers

February 21, 2025

4 questions with immunology researcher Susan Bullman

February 04, 2025

4 questions for mathematical oncologist Heiko Enderling, Ph.D.

January 28, 2025

Committed to making cervical cancer screening easier

January 08, 2025

11 new research advances from the past year

December 19, 2024

Finding hope for cancer patients in ferroptosis research

December 12, 2024

Advances in small cell lung cancer classification

November 25, 2024

Exploring pancreatic cancer vaccines: What’s next?

November 21, 2024

Read insights on the latest news and trending topics from MD Anderson experts, and see what drives us to end cancer.

How to take medications properly: 6 questions, answered

February 28, 2025

Clinical Ethics Fellow passionate about improving patient care

February 27, 2025

Senior speech pathologist: Patients are my No. 1 priority

February 19, 2025

Motivated to do more for pediatric patients

February 18, 2025

Find out what inspires our donors to give to MD Anderson, and learn how their generous support advances our mission to end cancer.

Three cancer survivors raise funds to support Colorado patients

October 03, 2024

Inflammatory breast cancer survivor finds hope at MD Anderson

October 24, 2023