- Diseases

- Acoustic Neuroma (16)

- Adrenal Gland Tumor (24)

- Anal Cancer (70)

- Anemia (2)

- Appendix Cancer (18)

- Bile Duct Cancer (26)

- Bladder Cancer (74)

- Brain Metastases (28)

- Brain Tumor (234)

- Breast Cancer (728)

- Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (2)

- Cancer of Unknown Primary (4)

- Carcinoid Tumor (8)

- Cervical Cancer (164)

- Colon Cancer (168)

- Colorectal Cancer (118)

- Endocrine Tumor (4)

- Esophageal Cancer (44)

- Eye Cancer (36)

- Fallopian Tube Cancer (8)

- Germ Cell Tumor (4)

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (2)

- Head and Neck Cancer (14)

- Kidney Cancer (130)

- Leukemia (342)

- Liver Cancer (50)

- Lung Cancer (286)

- Lymphoma (278)

- Mesothelioma (14)

- Metastasis (30)

- Multiple Myeloma (100)

- Myelodysplastic Syndrome (60)

- Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (6)

- Neuroendocrine Tumors (16)

- Oral Cancer (102)

- Ovarian Cancer (178)

- Pancreatic Cancer (162)

- Parathyroid Disease (2)

- Penile Cancer (14)

- Pituitary Tumor (6)

- Prostate Cancer (150)

- Rectal Cancer (58)

- Renal Medullary Carcinoma (6)

- Salivary Gland Cancer (14)

- Sarcoma (238)

- Skin Cancer (302)

- Skull Base Tumors (56)

- Spinal Tumor (12)

- Stomach Cancer (66)

- Testicular Cancer (28)

- Throat Cancer (92)

- Thymoma (6)

- Thyroid Cancer (100)

- Tonsil Cancer (30)

- Uterine Cancer (86)

- Vaginal Cancer (18)

- Vulvar Cancer (22)

- Cancer Topic

- Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Issues (22)

- Advance Care Planning (12)

- Biostatistics (2)

- Blood Donation (18)

- Bone Health (8)

- COVID-19 (360)

- Cancer Recurrence (120)

- Childhood Cancer Issues (120)

- Clinical Trials (628)

- Complementary Integrative Medicine (22)

- Cytogenetics (2)

- DNA Methylation (4)

- Diagnosis (240)

- Epigenetics (6)

- Fertility (62)

- Follow-up Guidelines (2)

- Health Disparities (14)

- Hereditary Cancer Syndromes (128)

- Immunology (18)

- Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (8)

- Mental Health (122)

- Molecular Diagnostics (8)

- Pain Management (62)

- Palliative Care (8)

- Pathology (10)

- Physical Therapy (18)

- Pregnancy (18)

- Prevention (940)

- Research (390)

- Second Opinion (78)

- Sexuality (16)

- Side Effects (616)

- Sleep Disorders (10)

- Stem Cell Transplantation Cellular Therapy (216)

- Support (408)

- Survivorship (330)

- Symptoms (182)

- Treatment (1794)

Clinical trial of new AhR inhibitor shows cancer might be even more wily than we thought

3 minute read | Published June 04, 2023

Medically Reviewed | Last reviewed by an MD Anderson Cancer Center medical professional on June 04, 2023

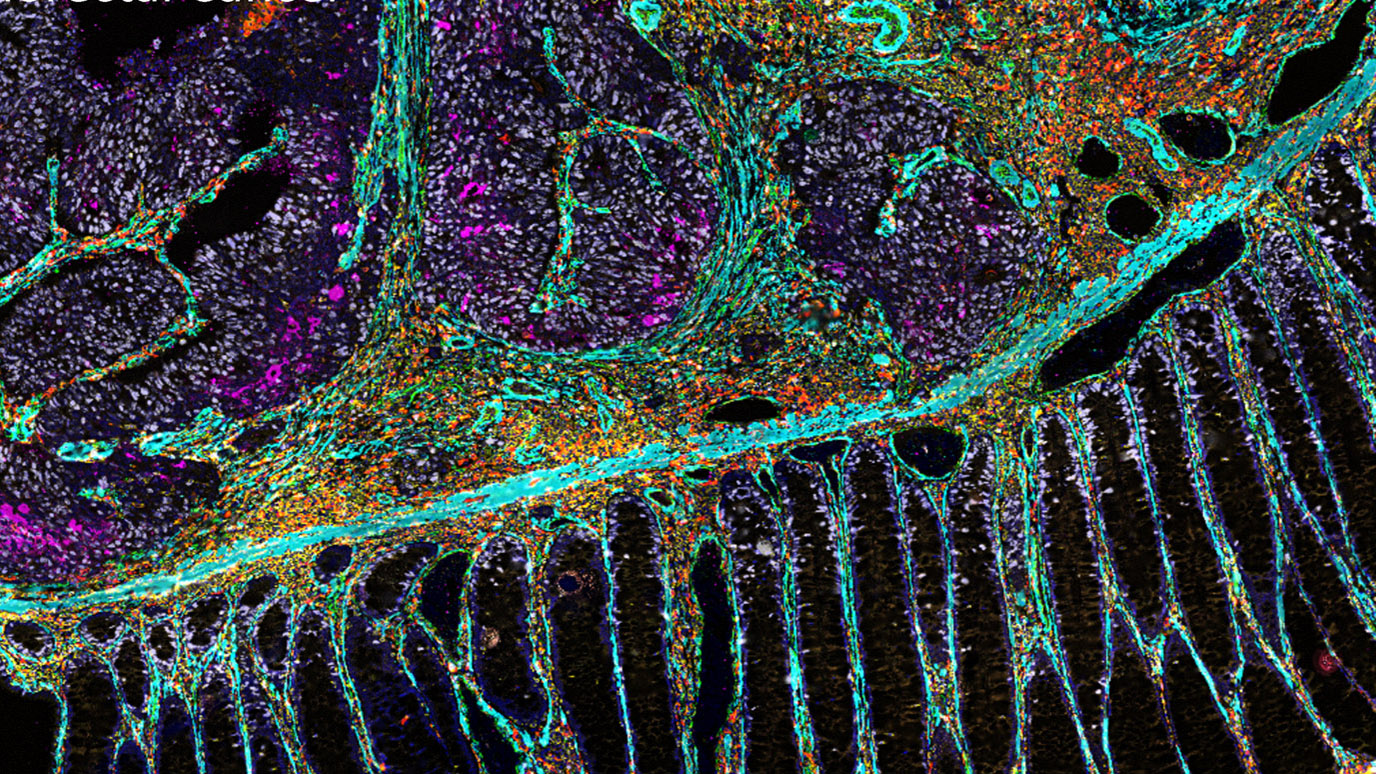

The human immune system is constantly attacking damaged cells that might turn into cancer, thus protecting us from these cells growing out of control and becoming malignant. However, cancer cells have many ways of protecting themselves from the body’s immune system. One of these is a protein, called aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), which is common on tumor and immune cells. When AhR is activated, it causes immunosuppression and promotes growth of the malignant tumor.

Researchers at MD Anderson — along with collaborators at Yale, as well as in Canada, the UK, Germany and Spain — have been conducting a Phase I clinical trial of a drug called BAY 2416964 that can block AhR. As a result, it should increase the activity of antigen-presenting cells and T cells and reduce the activity of immunosuppressive myeloid cells – thus allowing the immune system to see and attack the cancerous tumor.

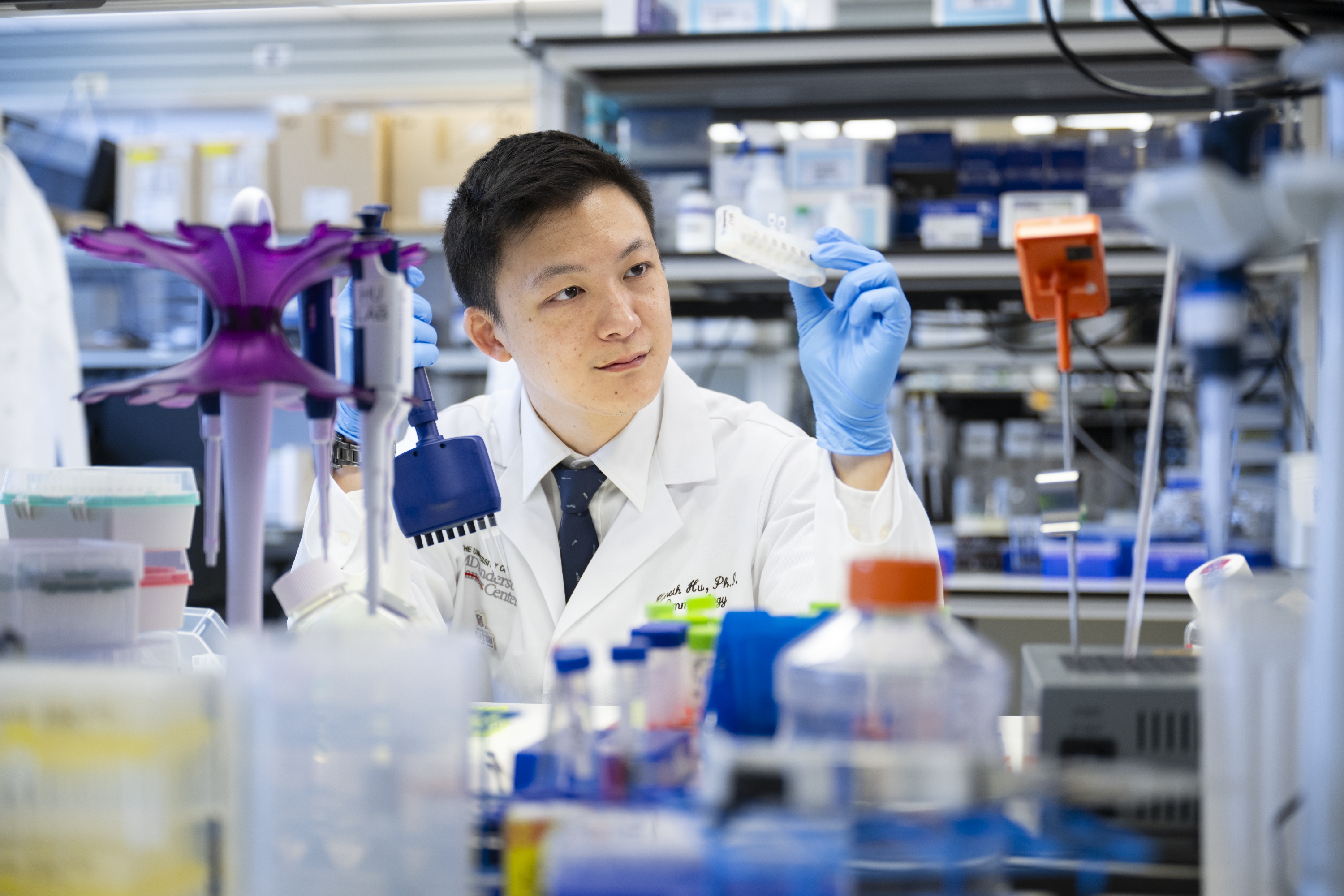

Ecaterina Dumbrava, M.D., assistant professor of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics at MD Anderson, presented the group’s findings at the 2023 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting.

“It’s a new drug with a new mechanism of action, which is always exciting,” Dumbrava says. “It’s part of what is called immune metabolomics, meaning it acts on the metabolism of the tumor and immune cells.”

Theoretical background seems promising

In theory, BAY 2416964 should help patients with advanced solid tumors of many common cancer types because it “antagonizes” the transcription factor activity of AhR by competing with its ligands. AhR is part of the pathway that changes tryptophan into kynurenine, and this pathway plays an important part in the metabolism of cancer progression and is believed to limit the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy, a type of immunotherapy commonly given to cancer patients. Efforts to interfere with the first part of the pathway, IDO, have led to disappointing results in clinical trials. However, AhR inhibition blocks downstream effects so, in theory, drugs like BAY 2416964 that act on AhR shouldn’t have the same issues.

“There is a difference between targeting only IDO versus targeting downstream enzymes in the tryptophan pathway as a possible alternative approach to restore the tumor immune response,” Dumbrava says. “Blocking AhR is expected to enhance immune response and improve outcomes in combination with PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors.”

The clinical trial, though, first needed to determine how BAY 2416964 acts on its own.

How the Phase I clinical trial works

The first part of the clinical trial enrolled patients with all types of solid tumors. Participants were given increasing amounts of BAY 2416964 to find the optimal dose. These 39 enrollees had cancers like colorectal cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, kidney cancer, ovarian cancer or thymus gland cancer that hadn’t responded to previous treatment. Although they experienced some side effects from BAY 2416964, none experienced severe reactions or had to discontinue the use of the drug as a result.

In addition, blood tests showed evidence of AhR inhibition. That meant the drug was working as intended.

With the safety of different doses of the drug established, the researchers next enrolled patients with non-small-cell lung cancer or head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Dashed hopes and next steps

Unfortunately, the results of the clinical trial weren’t as successful as the researchers had expected, based on preclinical models and a solid theory behind the drug. Of the 67 patients able to be evaluated for their response to the drug, only 32.8% had stable disease. There was also one patient with thymoma in the first part of the trial who achieved a partial response. No other patients achieved a partial or complete response to the drug.

Despite these findings, Dumbrava and her colleagues hope that BAY 2416964 may still play a valuable role in treating cancer when combined with other drugs, especially PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors.

“Safety data and observed pharmacodynamic effects support combination therapies,” Dumbrava says. “A study in combination with pembrolizumab, which is a type of PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor, is currently ongoing, and it’s possible that giving these two drugs together will be more effective than either one alone.”

Request an appointment at MD Anderson online or by calling 1-877-632-6789.

Related Cancerwise Stories

It’s a new drug with a new mechanism of action, which is always exciting.

Ecaterina Dumbrava, M.D.

Physician & Researcher