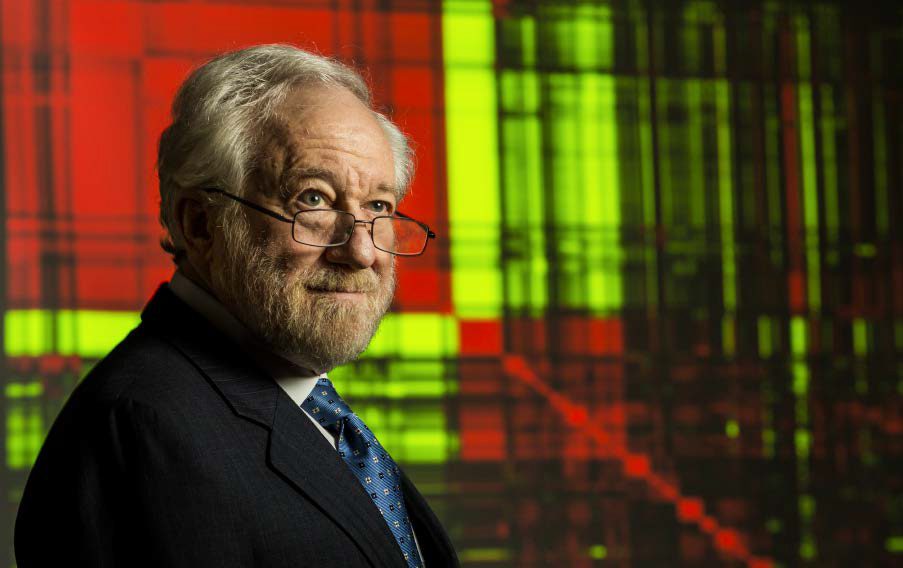

Surgeon. Engineer. Astronaut.

Orthopedic oncologist Robert Satcher has always reached for the stars

As a child, Robert Satcher dreamed of becoming an astronaut, an engineer and a doctor. He couldn’t decide on one, so he became all three.

“I was always pushing the boundaries,” he says, “looking for the next big adventure.”

Today, he’s an orthopedic oncology surgeon who treats bone cancer patients at MD Anderson.

But his high-flying résumé also includes stints as a chemical engineer and a NASA astronaut.

Photo: Wyatt McSpadden

Taste for adventure

Satcher grew up in the coastal town of Hampton, Virginia, where his father was a chemistry professor at Hampton University, a historically black institution, and his mother was an English teacher.

An avid encyclopedia reader who devoured articles about early explorers, young Satcher would stroll along the Virginia coastline and imagine ships from long ago on the horizon, making their way to shore. On board were the British colonials, Spanish conquistadors, French Huguenots and others who would colonize the Americas.

“I wondered what it was like to put your entire life on the line and sail to the other side of the world,” he says, “not knowing what you would find. How exhilarating and terrifying that must have been. I wanted to be part of that.”

Satcher enjoyed science and math and “tinkering with things to make them work.” At age 16 he enrolled in MIT where he majored in chemical engineering and graduated at the top of his class. But halfway through college, his interests began shifting toward medicine.

“A lot of my engineering classwork focused on solving medical problems,” he explains.

After graduating, he enrolled at Harvard University and earned his M.D. while simultaneously completing a Ph.D. in chemical engineering at MIT. “I appreciated how engineering interfaced with medicine.”

Along the way, he met several physicians and scientists who were also astronauts, including Ronald McNair, who later would die during the launch of the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1986, Leland Melvin, an aeronautics engineer and fellow Virginian, and Scott Parazynski, a veteran of five Space Shuttle flights and seven spacewalks. They shared their tales of adventure with Satcher, and he was hooked.

“I’ve always been interested in space travel,” says Satcher, who grew up watching “Star Trek,” “Star Wars” and “2001: A Space Odyssey” “But as I got older, I dismissed it as a childhood fantasy.”

But meeting fellow physicians who were astronauts convinced him that, “if they could do it, so could I.”

While working as an orthopedic oncologist at Northwestern University in Chicago, he succumbed to space’s pull and sent an application to NASA.

“My family and friends thought I was crazy,” he says, “but I had to try.”

It turns out he wasn’t crazy. He was accepted into NASA’s astronaut training program.

“I packed up,” Satcher says, “and headed to Houston.”

Practice Makes Perfect

Like surgical education, astronaut training was rigorous.

Practicing for spacewalks takes place mostly underwater, where conditions are similar to the weightlessness of space. Astronauts dive to the bottom of a 40-foot-deep NASA swimming pool that is two-thirds the length of a football field.

Full-scale working models of the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station’s experiment areas are submerged in the pool. This allows astronauts to practice every experiment or project they’ll perform while on board the shuttle or space station, before they head into orbit.

“Any task to be done in space is first rehearsed over and over again in the pool,” Satcher says. “Practice makes perfect, and when the environment is as foreign as the solar system, it’s a good idea to log as many practice hours as possible.”

To mimic the absence of light in deep space, pool training sometimes takes place in virtual darkness, with only a helmet-mounted headlamp providing a narrow beam of illumination.

“You don’t have cues to tell you which way is up and which way is down,” Satcher says. “It’s disorienting, but you adjust and you keep working.”

Mission accomplished

In 2009, Satcher’s training paid off when he and five other crew members boarded the Space Shuttle Atlantis and skyrocketed 220 miles to the International Space Station (ISS).

During the 11-day mission, dubbed STS-129, the doctor-turned astronaut participated in two spacewalks. Hovering high above the Earth while tethered to a safety harness, Satcher used the same surgical skills required for complex joint replacements to help repair two robotic arms on the space station’s exterior. He also installed an antenna to improve satellite communication. Crew members nicknamed him “the cable guy.”

The ISS, which travels at a speed of 17,150 miles per hour, covered approximately 4.5 million miles during the mission.

“I wish I’d earned frequent flyer miles,” Satcher quips. “I’d be set for life.”

And floating outside the spacecraft in a spacesuit afforded Satcher “spectacular” views.

“The colors on Earth are fantastic, like nothing you’ve ever seen.

There’s no crayon in the crayon box or Hollywood production to match what I saw.”

Drifting silently above Earth while looking back at the planet that looks “just like a globe,” is awe-inspiring and humbling, Satcher says.

“Earth is just a dot in the universe — a tiny, miniscule dot.”

Fat faces and more

But Satcher couldn’t be a tourist for long.

“Spacewalks average six to seven hours each, and you’re working the entire time,” he says. “The tasks are very involved and detailed. I had to pace myself and keep focused, just like in an operating room. My surgical training helped.”

Aboard the shuttle, he conducted experiments to determine how weightlessness affects the immune system, and how astronauts’ height changes when they go into outer space.

“They get taller,” he says. “Low-gravity conditions elongate the spine.”

Satcher grew two inches taller in space. Already 6’4” before the launch, he worried about fitting into the spacesuit he’d wear when re-entering Earth’s atmosphere.

“Fortunately, I squeezed in and made it fit,” he says.

Satcher also was the mission’s medical doctor and helped crew members deal with some unique medical problems.

“One of the first things astronauts complain about,” he says, “is nausea and vomiting.”

Apart from the unpleasantness of vomit globules floating around the capsule, space sickness can impede an astronaut’s piloting skills, he says.

“Weightlessness affects your inner ear, which throws off your balance, coordination and spatial orientation. Try navigating a shuttle under those conditions.”

Sleep deprivation is another frequent problem. At the speed it travels, the International Space Station orbits the Earth every 92 minutes, affording astronauts a view of 16 sunrises each day.

“Who could sleep through all that?” Satcher asks. “You spend a lot of time wide awake in outer space.”Nasal stuffiness and congestion is another common complaint.“

Being in space is like standing on your head,” Satcher says. “Without gravity, blood tends to float up to your face, which causes you to feel stuffy.”

“Fat face syndrome” is how he describes it.

“You look funny and you feel funny.”

Satcher retired from NASA and joined MD Anderson in 2011, but his taste for adventure persists. Someday, he says, he may go back.

"There’s nothing like those last 15 seconds or so of the countdown, when you realize you’re on your way. It’s a thrilling ride.”

ON TOP OF THE WORLD

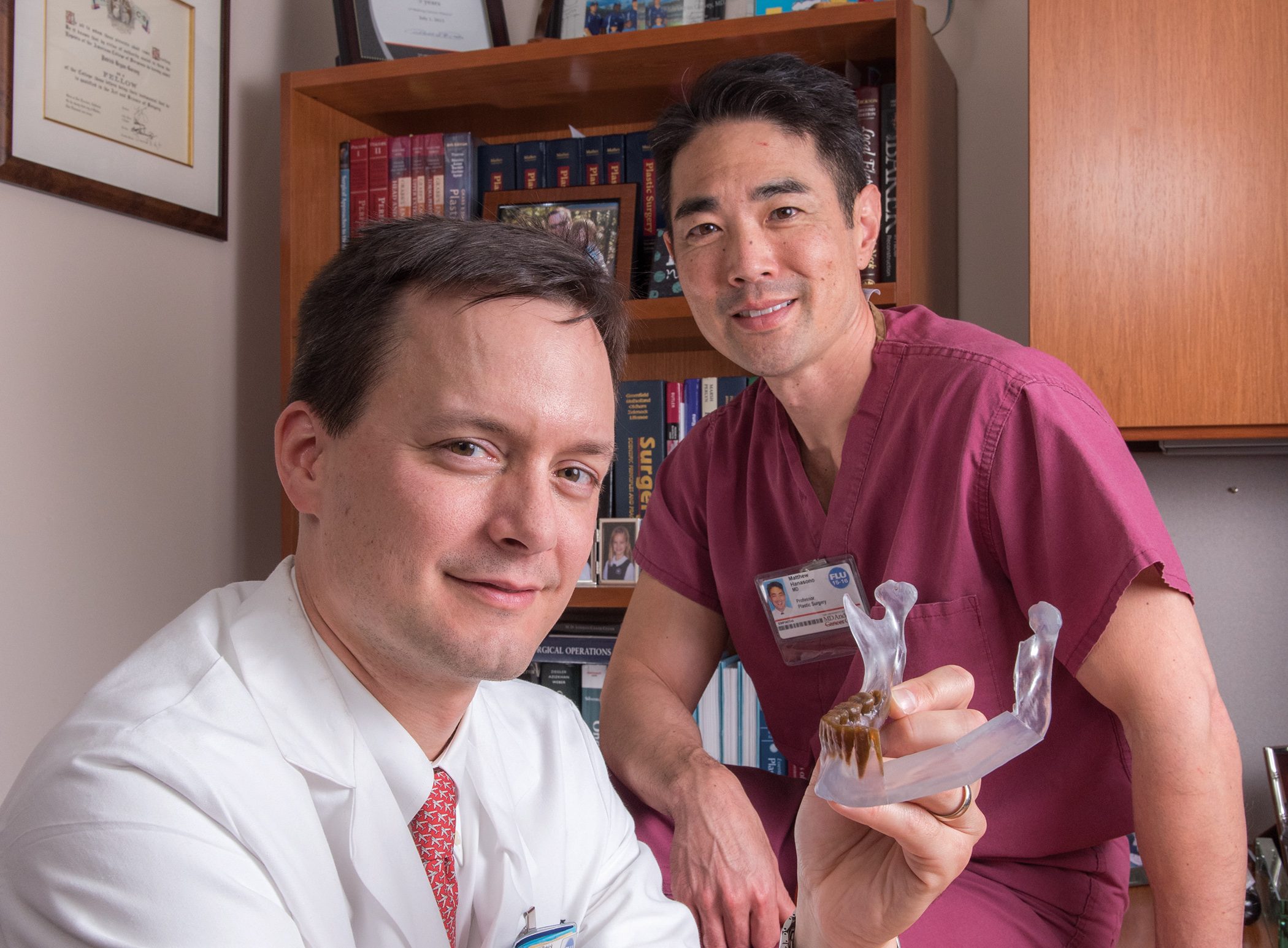

Ellen Baker: MD Anderson doctor, NASA astronaut

When Ellen Baker, M.D., was completing medical school in the late 1970s, she read a newspaper article that announced NASA was accepting astronaut applications.

Women, in particular, were urged to apply.

“I never imagined I could be an astronaut,” Baker says. “When I was growing up, only boys became astronauts.”

But the newspaper article got Baker thinking about the possibility of a career in space exploration. After completing an internal medicine residency, she joined NASA as a medical officer in 1981, and was selected as an astronaut in 1984.

Over the next 11 years, she flew in space on three missions:

1989, mission STS-34

The crew of Space Shuttle Atlantis deployed the Galileo probe to explore Jupiter, mapped atmospheric ozone on Earth and conducted medical and scientific experiments.

1992, mission STS-50

Space Shuttle Columbia was the first flight of the United States Microgravity Laboratory and the first Extended Duration Orbiter flight.

For more than two weeks, the crew conducted scientific experiments involving crystal growth, fluid physics, fluid dynamics, biological science and combustion science.

1995, mission STS-71

This was the first space shuttle mission, flown aboard Atlantis, to dock with the Russian Space Station Mir, and involved an exchange of the station crew. The crew also performed various life sciences experiments and data collections.

After returning from space, Baker held a variety of NASA positions that supported the Space Shuttle, Space Station and Exploration Programs.

She also was appointed chief of the medical branch and education branch for NASA’s Astronaut Office.

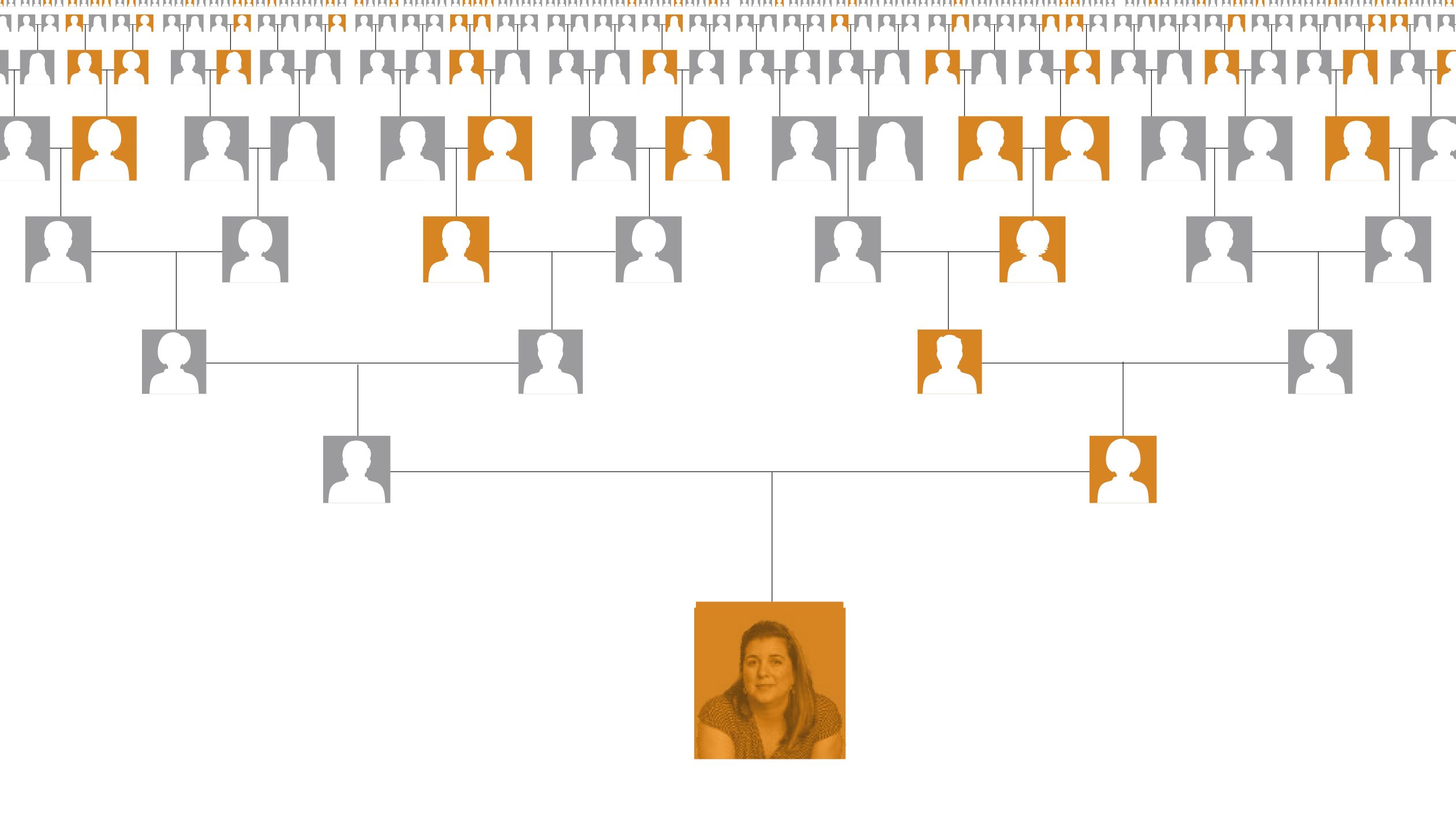

In 2011, she retired from NASA. She joined MD Anderson in 2014, where she heads Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes). The ECHO program connects cancer specialists at MD Anderson with providers in rural and urban areas, domestically and internationally, who work with underserved populations.

Spaceflight gave Baker a deep appreciation for the “oneness” of Earth.

“From space you can’t see where one country starts and where another ends,” she says. “It makes you feel that we’re all one people.”