Inheriting a greater risk for cancer

Genetic testing can detect many hereditary cancer syndromes, allowing for early prevention

When Nonnie Arriola was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 37, her first question was, “Why?” No one in her family had cancer, and Arriola was surprised to be diagnosed with the disease at such a young age.

“I thought it might be genetic,” she says. “I worried about my family and my children.”

Hereditary cancers are caused by genetic mutations passed down from parents to children. The National Cancer Institute estimates these genetic “mistakes” play a role in about 5 to 10% of all cancers.

More than 50 hereditary cancer syndromes have been identified, and genetic tests have been developed to detect many of these.

Photo: Wyatt McSpadden

“New patients want to know, ‘Why did I get this disease and is my daughter at risk?’” says Karen Lu, M.D., chair of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine. “In some cases, we can actually give them that answer.”

Knowing that a particular cancer is hereditary is extremely powerful, not only for patients but also for their families, says Banu Arun, M.D., professor of Breast Medical Oncology.

Lu and Arun are co-medical directors of MD Anderson’s Clinical Cancer Genetics program. Launched in 2002, the program employs 13 counselors in multiple MD Anderson clinics to advise patients diagnosed with inherited forms of cancer.

“Physicians in those clinics are aware of the importance of genetic testing and champion the program,” says Arun. “The process is simple.”

Counselors first meet with patients to discuss family history and determine if testing is necessary. Patients who decide to proceed undergo a simple blood draw. Results are back within weeks. Counselors and patients discuss the results and potential next steps.

After undergoing genetic testing, Arriola learned she had a BRCA1 mutation, which significantly increases the risk of developing breast and ovarian cancers.

After completing treatment, she had a double mastectomy to reduce the risk of the cancer recurring. Earlier this year, she completed reconstructive surgery and is doing well.

First-degree relatives — parents, siblings or children — of people with cancer-causing genetic mutations have a 50% chance of inheriting the same mutation, which dramatically raises their own cancer risk.

They’re treated in MD Anderson’s high-risk clinics, where they may undergo more stringent cancer screenings, take anti-cancer drugs, are encouraged to adopt healthier lifestyles, or even have surgery to remove ovaries, fallopian tubes and/or breasts — an option known as preventive or prophylactic surgery.

“It’s a positive ripple effect for the family,” says Arun. “We’ve found when relatives are tested and take preventive measures, they can avoid the devastating cancers that run in their families.”

After undergoing genetic testing, Arriola’s mother and daughter discovered they carry her same BRCA1 mutation. They’re taking action.

“My mother was having yearly mammograms but is now going every six months.

She’s also having her ovaries removed this year,” Arriola explains. “My daughter is only 20, but she’ll start screening early and is considering future options. She wants to have kids one day, and now knows she may need to start earlier than planned.”

Arriola also is undergoing regular ovarian cancer screenings.

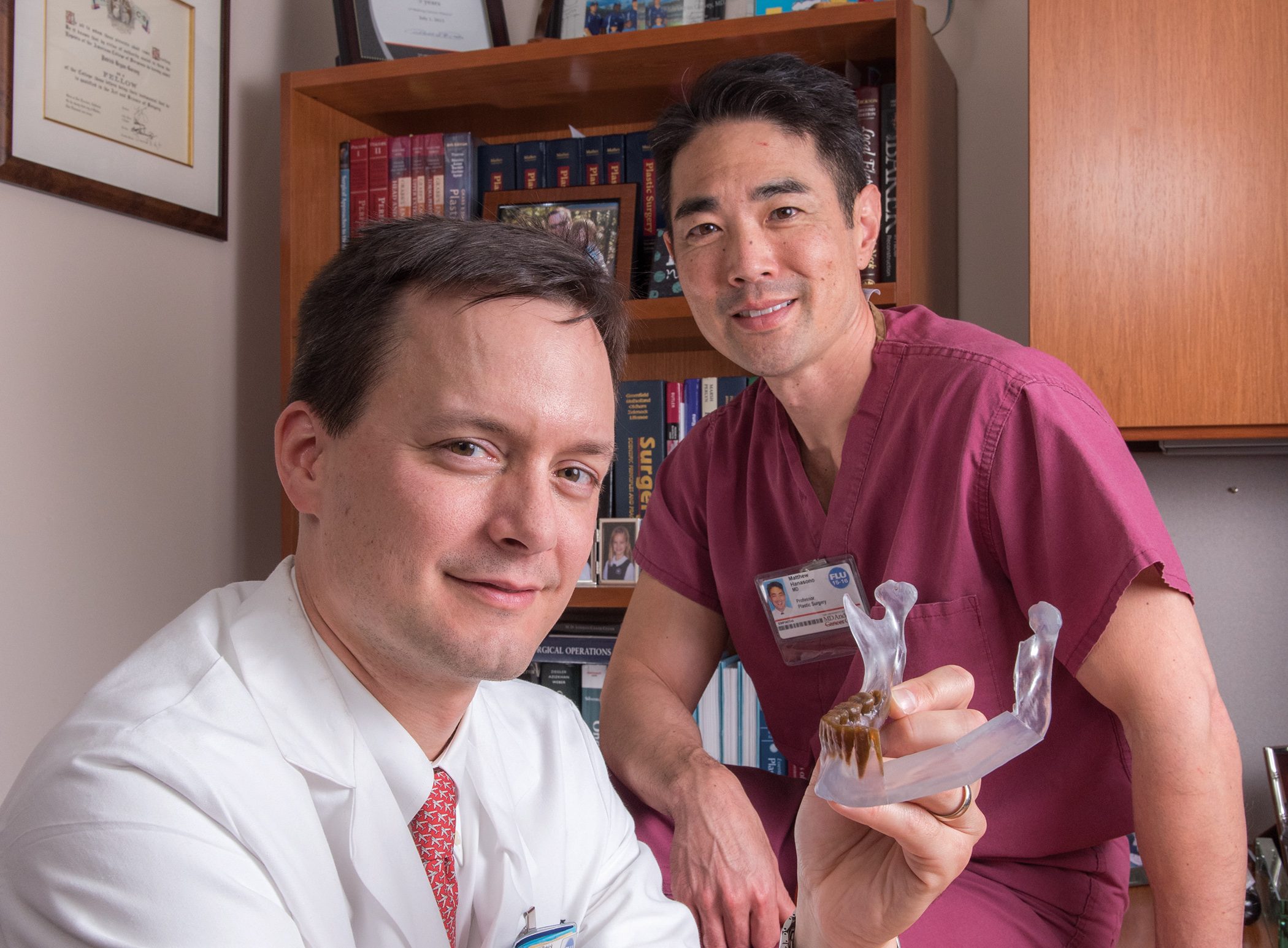

Karen Lu, M.D., left, and Banu Arun, M.D., are co-medical directors of MD Anderson’s Clinical Cancer Genetics program.

Karen Lu, M.D., left, and Banu Arun, M.D., are co-medical directors of MD Anderson’s Clinical Cancer Genetics program.

Photo: Wyatt McSpadden

Clinical Cancer Genetics program faculty members are conducting research to increase existing knowledge. They’re building an evergrowing genetic database that’s influencing screening guidelines and prevention strategies.

Current guidelines recommend that women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations have their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed by ages 35 to 40, explains Lu, although doing so will cause early menopause.

However, research conducted in the last five years suggests ovarian cancer may begin in the fallopian tubes. An ongoing clinical trial conducted through MD Anderson’s High Risk Ovarian Cancer Screening Clinic will determine if a two-stage surgery — removing the fallopian tubes first and ovaries later — can delay menopause while still preventing cancer.

Studies like this are made possible through information obtained through genetic testing.“We know that patient care and research goes hand in hand,” Arun says. “We need to ask and answer meaningful clinical questions while we’re seeing patients.”

Heredity’s role in cancer

Below is the National Cancer Institute’s list of the most common inherited cancer syndromes, the gene or genes that are mutated in each, and the types of cancer most often associated with them.

Hereditary breast cancer and ovarian cancer syndrome

Genes: BRCA1, BRCA2

Related cancer types: Female breast, ovarian, and other cancers, including prostate, pancreatic and male breast cancer

Li-Fraumeni syndrome

Gene: TP53

Related cancer types: Breast cancer, soft tissue sarcoma, osteosarcoma (bone cancer), leukemia, brain tumors, adrenocortical carcinoma (cancer of the adrenal glands) and other cancers

Cowden syndrome (PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome)

Gene: PTEN

Related cancer types: Breast, thyroid, endometrial (uterine lining) and other cancers

Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer)

Genes: MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM

Related cancer types: Colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, renal pelvis, pancreatic, small intestine, liver and biliary tract, stomach, brain and breast cancers

Familial adenomatous polyposis

Gene: APC

Related cancer types: Colorectal cancer, multiple non-malignant colon polyps, and both non-cancerous (benign) and cancerous tumors in the small intestine, brain, stomach, bone, skin and other tissues

Retinoblastoma

Gene: RB1

Related cancer types: Eye cancer (cancer of the retina), pinealoma (cancer of the pineal gland), osteosarcoma, melanoma and soft tissue sarcoma

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (Wermer syndrome)

Gene: MEN1

Related cancer types: Pancreatic endocrine tumors and (usually benign) parathyroid and pituitary gland tumors

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2

Gene: RET

Related cancer types: Medullary thyroid cancer and pheochromocytoma (benign adrenal gland tumor)

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome

Gene: VHL

Related cancer types: Kidney cancer and multiple noncancerous tumors, including pheochromocytoma