A Healing Light

How lasers are used to attack ‘inoperable’ brain and spinal tumors

Photo: Wyatt McSpadden

When Allison Easley awoke one morning with soreness under her right armpit, she thought she’d pulled a muscle. But the pain soon became worse, and her lymph nodes started to swell.

“I wondered if I’d caught an infection from one of the kids,” says Easley, 29, a special events photographer who days earlier had taken class portraits at an elementary school.

Antibiotics prescribed by her family doctor didn’t help, and when her pain became unbearable, Easley, who lives just north of San Antonio, visited her local emergency room. Doctors there did a lymph node biopsy and found melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer. It wasn’t Easley’s first encounter with the disease.

Ten years earlier, at age 19, she’d been diagnosed with melanoma when a suspicious-looking mole alerted doctors to the disease. They surgically removed it, allowing Easley to live cancer-free for almost a decade.

But now, the melanoma was back with a vengeance.

Imaging scans revealed thirty tumors scattered throughout her body. Within months, six would spread to her brain.

“The possibility I’d relapse was always at the back of my mind,” Easley says. “When you’ve had cancer, you’re always waiting for the other shoe to drop.”

Her cancer had been spreading swiftly and silently, and was now stage 4 — the most advanced form of the disease.

This time, Easley sought care at MD Anderson, where doctors prescribed chemotherapy, radiation and powerful new immunotherapy drugs that rallied her immune system and helped her body fight hard.

The drugs eliminated all Easley’s tumors — except those in her brain.

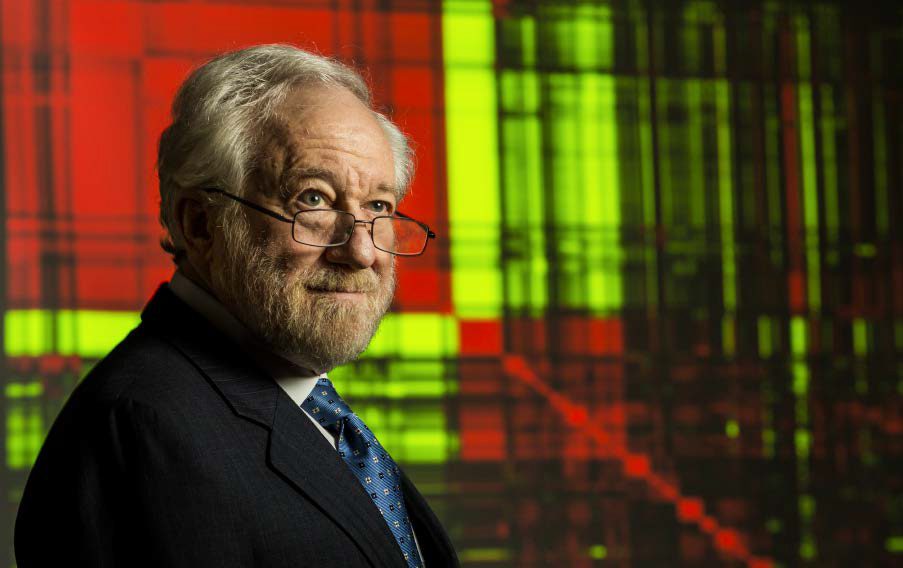

“A protective network of blood vessels known as the blood-brain barrier prevents foreign substances from crossing into the brain, but it also can prevent life-saving drugs from entering,” says Ganesh Rao, M.D., associate professor of Neurosurgery at MD Anderson’s Brain and Spine Center.

Brain surgery to remove Easley’s tumors seemed like her only remaining option, but there was a problem. A particularly large tumor had embedded itself deep in the center of her brain, between the right and left hemispheres. Any attempt to reach it surgically would most certainly damage areas that control motor skills affecting coordination and movement.

“This is the juncture where many doctors tell patients their condition is inoperable,” says Rao. “But at MD Anderson, we have another way to reach unreachable tumors.”

Photo: Nick de la Torre

Turning up the heat

The cancer center is one of a select few in the nation using a probe that’s specially designed to heat and destroy brain and spinal cord tumors — regardless of their size or location. The treatment is known as laser interstitial thermal therapy, or LITT. Put simply, the name means that laser heat penetrates interstitially — inside tissue — to destroy tumor cells.

“Many types of tumors previously thought to be inoperable can be treated with this technology, including aggressive tumors that originate in the brain or spinal cord, or tumors that have spread to the brain or spine from other areas of the body,” says Sujit Prabhu, M.D., a professor of Neurosurgery who works side by side with Rao in the Brain and Spine Center. “We’re visited by a lot of patients from around the world who’ve been told nothing can be done. We offer them LITT.”

How it works

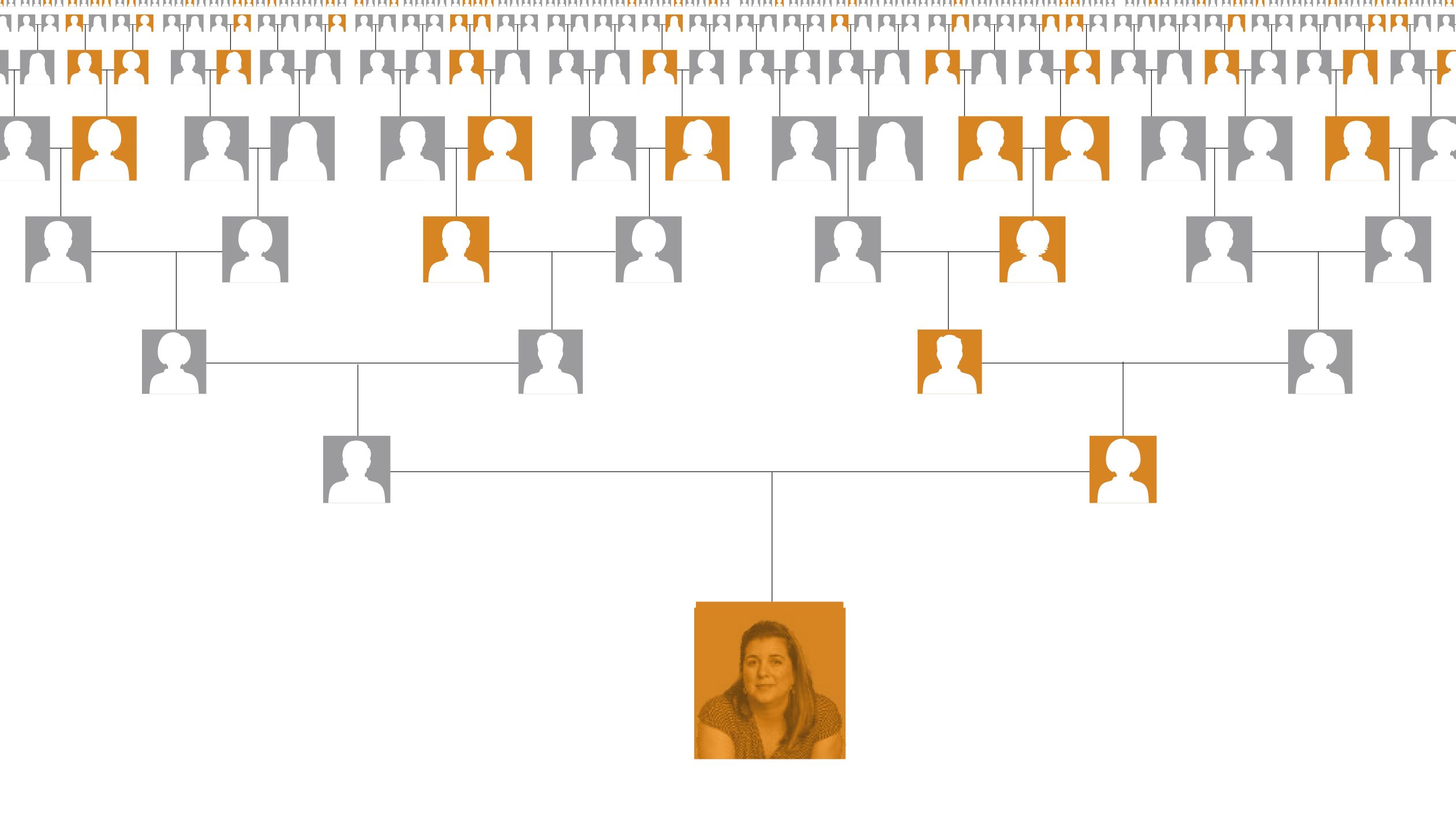

To perform the procedure, surgeons first study MRI scans of the patient’s brain to create a map of coordinates they’ll follow as they navigate the probe through the brain and into the tumor. The patient is then put to sleep with general anesthesia and placed inside an MRI machine that’s open on both ends.

Next, a dime-sized hole is drilled in the patient’s skull, and the probe is inserted into the brain. Guided by the previously mapped coordinates, the surgeon carefully advances the probe through the brain and into the middle of the tumor. Because the probe is no wider than a pencil lead, it creates the tiniest of tunnels.

“Tissue damage is nil or close to nil — nothing like that caused by surgical instruments,” says Prabhu.

With the probe in place, the doctor fires a laser beam from its tip.

Intense heat emanates from the laser and destroys the tumor’s cells.

“Each burst lasts anywhere from 30 seconds to a few minutes and generates heat ranging from 158 to 176 degrees Fahrenheit,” Rao explains. “It ‘cooks’ the tumor from the inside out.”

Because the patient is continuously imaged inside the MRI, the surgeon can watch the tumor destruction on a monitor as it’s happening.

With each firing of the laser, the tumor turns green, yellow, orange, then red as it becomes increasingly hotter. Temperatures are displayed on-screen, confirming that the targeted tissue is thoroughly “cooked” and dead.

Multiple passes with the probe can be made for larger tumors.

“The system knows to burn precisely to the edges of the tumor without crossing over into healthy tissue,” Rao says. “A built-in, emergency off switch engages automatically if the laser heat starts going where it shouldn’t.”

The key to success, Rao says, is achieving the right temperature in the right spot.

“With this technology, we have that assurance,” he says. “We watch the cancer cells on-screen as they’re dying.”

After Rao used the procedure on Easley eight months ago, five of her six brain tumors vanished, and the sixth — the troubling one buried deep in her brain — has shrunk to a fraction of its original size.

“I return to MD Anderson every three weeks for scans, and each time the tumor has shrunk a little more,” she says. “Pretty soon, it won’t be there at all.”

Easley looks forward to hearing she’s “NED,” a medical acronym meaning “no evidence of disease.”

“The three most beautiful letters in the alphabet,” she says with a grin.

Photo: Wyatt McSpadden

Pamela’s story

Like Easley, Pamela Lynn had cancer that at first glance seemed inoperable.

Lynn, a high-tech firm retiree, visited her family doctor two years ago complaining of abdominal discomfort. A CT scan revealed a 3-pound, football-shaped tumor on her kidney. The tumor had spread to multiple spots on her lungs and to two locations on her spine.

“I was flabbergasted,” says the 62-year-old resident of Round Rock, Texas, just north of Austin. “I don’t smoke, I don’t drink, and no one in my immediate family has had cancer.”

Doctors at Lynn’s local hospital spent nine hours removing her left kidney with its attached tumor. In the same surgery, they removed only a small piece of one spinal tumor, and didn’t try to remove the second one.

The tumors, they said, were inoperable.

“They were wrapped around the spinal cord, touching vital nerves and arteries, and the doctors just couldn’t risk removing them,” says Lynn, who spent four days recovering in the hospital with hooks and screws implanted in her spine to keep it from collapsing.

Not ready to give up, Lynn headed to MD Anderson, where she arrived in a wheelchair and back brace. She enrolled in a clinical trial for an experimental medication that significantly reduced her lung tumors but did nothing for those on her spine.

“The blood-brain barrier,” Rao explains, “shields the spine as well as the brain.”

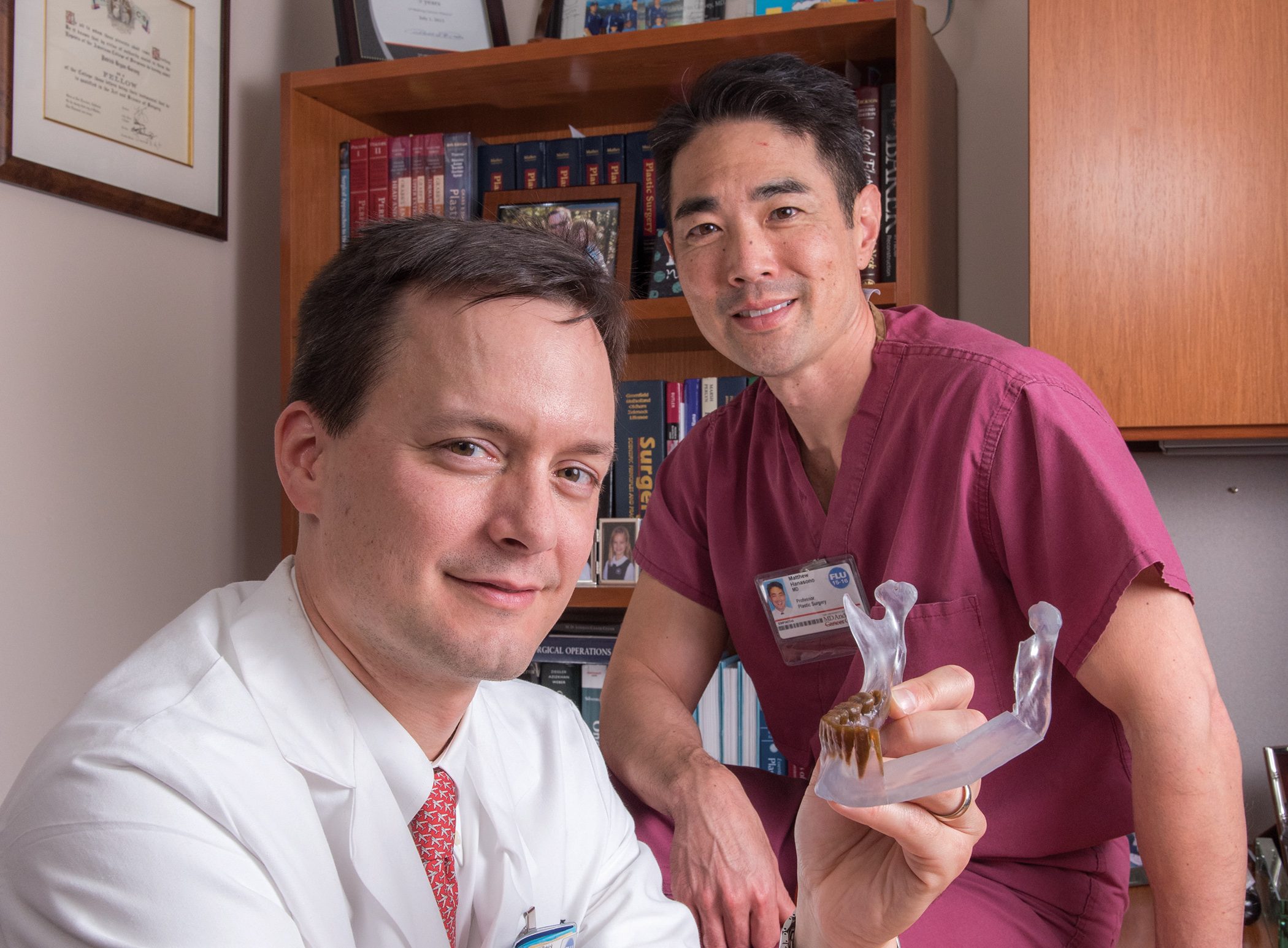

Having exhausted the usual options, Lynn’s oncologist referred her to Claudio Tatsui, M.D., assistant professor of Neurosurgery and a spine surgery specialist in the Brain and Spine Center. Tatsui is the first in the world to pioneer laser interstitial thermal therapy for the treatment of spinal tumors.

“We’d successfully used LITT to eliminate brain tumors,” he says, “so I thought, ‘Why not spinal tumors?’”

He used the technique on Lynn a year ago.

The effect was dramatic. Images taken the next day showed no obvious signs of cancer in her spine. And her recovery took days instead of weeks.

“I went home the day after surgery with just two round bandages covering two small incisions in my back,” she marvels. “I walked out of the hospital on my own, with no pain and no back brace.”

Today, she travels the world with her husband, creates stained glass art, researches her family’s Swedish ancestry and enjoys being “mom” to her three cherished Cocker Spaniels.

“If I hadn’t come to MD Anderson,” she says, “I wouldn’t be doing any of those things.”

Combined technologies

Laser and MRI technologies have been in existence for a couple of decades, Tatsui says. However, what is new is the combination of the two to allow imaging in real time.

“This technology is unique in that it allows a surgeon to precisely control where the treatment is delivered, and to see the actual effect on the tumor tissue as it’s happening,” he explains. “This lets us adjust the treatment continuously as it’s delivered, and increases our precision in eliminating tumor tissue and sparing surrounding healthy tissue.”

If the treatment fails to achieve the desired results, patients can still undergo traditional surgery afterward, he adds.

“But standard surgery has a higher risk of blood clots and infection,” Tatsui says.

“And it requires patients to discontinue their chemo and radiation for several weeks. There’s no such schedule interruption with LITT.”

Patients are alert, responsive and walking within hours, he says, and ready to go home the next day. With traditional surgery, recovery can take weeks, sometimes months.

Virtually anyone can undergo the procedure, except heart patients with implantable pacemakers or defibrillators that can be damaged by MRI imaging. Even then, newer-model heart devices can be programmed to be safe during an MRI.

LITT is a game changer for virtually anyone with a brain or spinal tumor, Tatsui says.

“This technology is lighting the way to improved treatment, and allowing us to go where we’ve never gone before.”