Vaccine to personalize colorectal cancer treatment

Customized vaccines deliver extremely personalized therapy

A Colorectal Cancer Moon Shot team is exposing treatment-resistant tumors to an immune attack

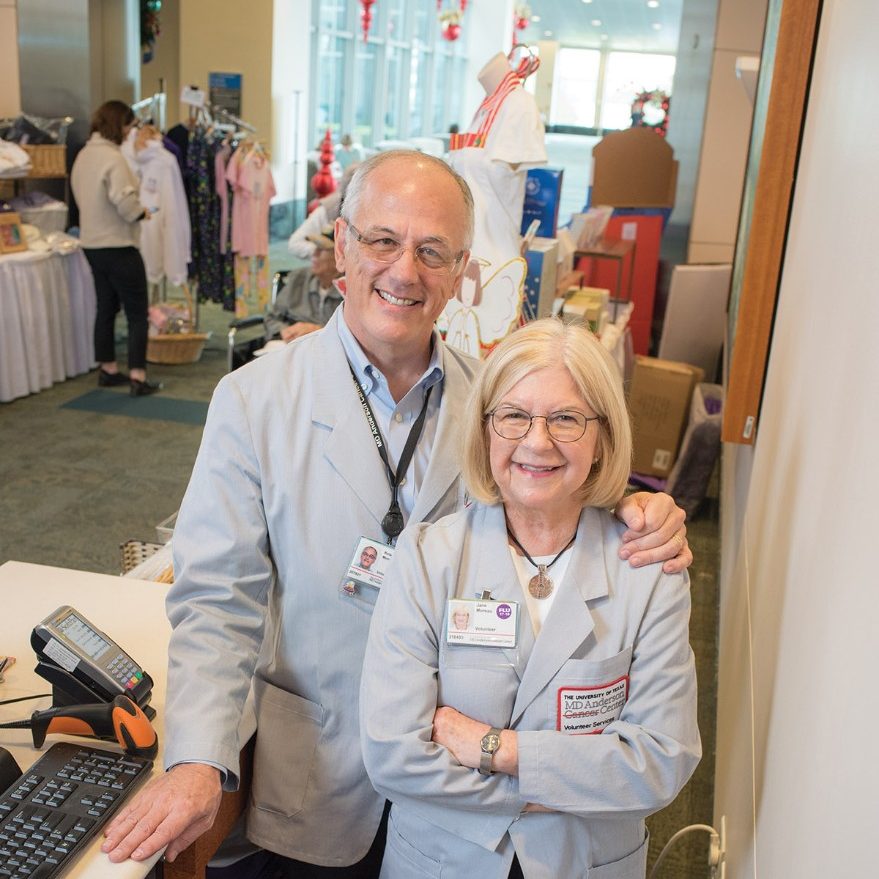

photo by Wyatt McSpadden

Immunotherapy has taken hold as an effective treatment for a variety of advanced cancers, but so far, colorectal cancer has stubbornly resisted.

However, research led by MD Anderson shows that resistance could be struck down. The recent international clinical trial helped expose a weak spot that leaves about 5% of colorectal tumors receptive to immune attack. (see the related story "5 years in, the Moon Shots Program is primed for continued progress" )

Now, a team in the Colorectal Cancer Moon Shot™ of MD Anderson’s Moon Shots Program™ is expanding on this discovery to benefit even more patients.

Michael Overman, M.D., associate professor of Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology, led a Phase I clinical trial testing whether a special form of vaccination can recruit the immune response that’s missing in most patients.

“Each patient is different, so we’re developing a personalized vaccine based on specific targets we identify on a patient’s tumor,” Overman says. “The initial question was ‘can we do this in a feasible amount of time for our patients?’ The pilot study showed we could.”

Overman and colleagues are combining these tailored vaccines with an approved drug that protects and boosts immune response to see if the one-two punch can help more colorectal cancer patients.

At first, analyzing a patient’s surgically removed tumor and developing a vaccine against 10 specific targets on the tumor took nine months, says Greg Lizée, Ph.D., associate professor of Melanoma Medical Oncology, whose research focuses on the immune system. Now the time from surgery to vaccine treatment is three months and falling.

The trial opened in November 2016. By late summer, 17 patients with metastatic colon cancer had received customized vaccines. Several had their tumors shrink or remain stable temporarily, says Scott Kopetz, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology and co-leader of the moon shot.

In September, the team added to the vaccine regimen a drug called Keytruda that supports the immune system’s attack on tumors.

The rationale for the combination trial is that the vaccine will prime white blood cells called T cells to find and attack the targets on a patient’s tumor, and Keytruda will keep the response going by blocking an off switch on those T cells that can shut down immune response.

Getting his life back

For Jerry “JT” Burk, a 66-year-old architect from Houston and one of Kopetz’s patients, the trial came along when his colorectal cancer had spread to his lungs and he was almost out of options. Chemotherapy slowed the disease, but its side effects were taking an increasing toll on his quality of life.

“Getting off chemo and going on the trial in November (2016), I felt almost normal,” Burk says. “I could do things like travel, because my immune system was no longer compromised (by the chemo). There were few side effects, and tumor growth slowed.”

In March, his tumor growth increased, and he stepped off the trial and onto chemotherapy again.

“You have to think long and hard when you’ve been on chemo so long and then you back off of it and get your life back,” Burk says. “It’s a hard decision. But it’s a bridge, and I’m hopeful.”

The bridge worked, and in September, Burk moved on to the second phase of the immunotherapy trial.

Burk is doing well, Kopetz says, but it’s too early to report overall results for the seven patients who had customized vaccines developed initially and have since proceeded to the combination trial.

How vaccines work

Some vaccines prevent cancer by destroying invading toxins or foreign substances that cause infection. For example, vaccines for the hepatitis B virus prevent liver cancer and vaccines for the human papillomavirus prevent cervical, anal and some throat cancers.

Lizée and colleagues are developing a different type of vaccine called a therapeutic vaccine, which triggers an attack against established cancer. Earlier versions of such vaccines largely failed because they targeted single invading substances that were not mutated, so T cells that attack invaders often ignored them, he says.

The team identifies “neoantigens” – targets that are unique to the tumor, using an exhaustive process made possible by recent technological advances.

Ten such targets are found for each patient. A vaccine against all 10 neoantigens is developed and given on a set schedule during the clinical trial, along with Keytruda.

Of the first 100 neoantigens identified for 10 patients, 98 were unique to the individual patients.

“Every patient is his own universe,” Lizée says. “This might be the ultimate in personalized therapy.”

A genetic flaw allows immunotherapy to help certain patients with colorectal cancer

A practice-changing clinical trial conceived and led by MD Anderson investigators showed that metastatic colorectal cancer patients with a specific genetic defect respond well to a common cancer immunotherapy drug.

About 5% of patients with colorectal cancer that has spread to other organs have a flaw in the genes that repair their tumors’ cancer-causing DNA damage. Their tumors harbor an increasing number of DNA mutations, which attract the attention of immune system T cells that hunt down and destroy cancer cells.

The findings suggested that immunotherapy, a treatment in which the immune system is used to attack cancer cells, could help these patients, says Michael Overman, M.D., associate professor of Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology.

“Traditional chemotherapy and targeted therapies have little effect for patients with these tumors,” he says, “so hopes for immunotherapy’s effectiveness were high.”

Overman and Scott Kopetz, M.D., professor of Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology, recommended a clinical trial for these patients to Bristol-Myers Squibb, the company that makes the immunotherapy drug nivolumab, known commercially as Opdivo.

The international trial that resulted showed tumors shrank in 23 of the 74 patients enrolled. In the other 51, disease progression halted for at least 12 weeks.

“That level of response and disease control is unheard of in these heavily pretreated patients, outside of frontline treatment,” Overman says.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved nivolumab as second-line therapy for these patients this past July, and clinical trials are underway to test the drug as frontline treatment. The FDA also approved another immunotherapy drug, Merck’s pembrolizumab, known commercially as Keytruda, for patients with tumors harboring this defect regardless of cancer type. Based on early results, the National Cancer Center Network recommended in November the testing of all metastatic colorectal cancer patients for the genetic defect.