A gut reaction

Research ties the diversity of bacteria in the digestive tract to the impact of cancer immunotherapy

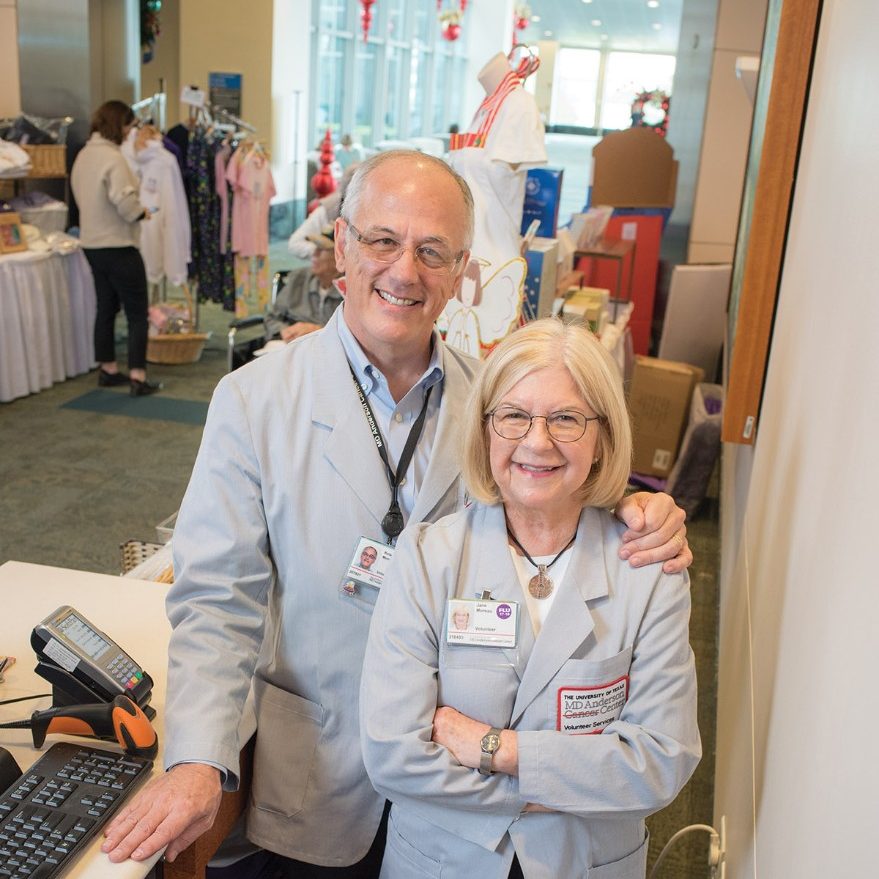

photo by Wyatt McSpadden

Bacteria and other microbes live in us by the trillions – not as agents of infectious disease but as vital allies with important roles in maintaining human health.

By most estimates, these useful invaders – collectively known as a person’s microbiome – outnumber the body’s own cells.

In recent years, scientists have begun to describe the distinctive features of this “microbiome” and to understand in greater detail its impact on essential processes such as digestion and immune response.

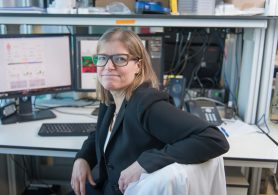

Jennifer Wargo, M.D., associate professor of Surgical Oncology, leads a team of researchers at MD Anderson uncovering a connection between the blend of bacteria found in late-stage melanoma patients’ digestive tracts and their response to a widely used immunotherapy drug that stimulates the immune system to fight off disease.

“Greater diversity of bacteria in the gut microbiome is associated with both a higher response rate to treatment and longer progression-free survival,” Wargo says.

The researchers studied fecal samples from 43 patients treated with immune checkpoint blockade drugs that unleash a block on the immune system so it can fight cancer. Their study indicated that certain characteristics of the patients’ microbiomes correlate with slower disease progression, while other qualities are associated with advancing the disease.

Findings revealed that patients with more varied types of bacteria in their digestive tracts had longer median progression-free survival, defined as the point in time when half the patients experienced progression of their disease.

“The microbiome appears to shape a patient’s response to cancer immunotherapy, which opens potential pathways to use the microbiome to assess a patient’s fitness for immunotherapy and to manipulate it to improve treatment,” says Wargo, who is also co-leader of the Melanoma Moon Shot™, part of MD Anderson’s Moon Shots Program™ to reduce cancer deaths by accelerating the development of therapies from scientific discoveries.

Research has shown that a persons’ microbiome is unique and can be altered by diet, exercise, antibiotics, probiotics or through transplantation of fecal material. Treating the microbiome would open a completely new avenue of cancer treatment.

In November, MD Anderson signed an agreement with Seres Therapeutics, which makes live bacterial products, and the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, to launch a clinical trial in 2018 that combines immunotherapy with treatment to improve the microbiome of patients with stage 4 melanoma.

The clinical collaboration builds on Wargo’s research, which was funded initially by the Melanoma Moon Shot.

In her current study, patients were treated with an immune checkpoint inhibitor, a class of drugs that blocks a protein named PD1 that prevents the immune system from attacking cancer. Immune checkpoint inhibitors release the block, which then frees T cells, the attack cells of the body, to locate and attack tumors.

“Anti-PD1 immunotherapy is effective for many, but not all, metastatic melanoma patients, and responses aren’t always durable,” Wargo says.

Researchers are seeking clues to understand these varied results to extend immunotherapy success to more patients.

“Evidence from lab and animal model research had previously indicated a relationship between solid tumors, immune response and the microbiome,” says Vancheswaran Gopalakrishnan, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Wargo’s lab. “Our study was the first of its type to look at the relationship between the microbiome and immunotherapy response in patients.”

Specific bacterial types also had an apparent effect. Abundant Faecalibacterium was associated with longer progression-free survival and an abundance of Bacteroidales correlated with more rapid disease progression.

Patients with favorable microbiomes showed strong evidence of a more robust immune response. They had higher levels of immune cells circulating in the blood and penetrating the tumor, as well as lower levels of a variety of immune-suppressing cells.

To further investigate the link between the microbiome and response to therapy, Wargo and colleagues transplanted stool from patients into germ-free mice. Some of the patients had responded to immunotherapy drugs, and some had not. The mice that received transplants from responding patients had significantly reduced tumor growth, higher densities of beneficial immune T cells, and lower levels of immune suppressive cells. They also had better outcomes when treated with immune checkpoint blockade inhibitors.

Wargo cautions that there’s still a lot to learn about the relationship between the microbiome and cancer treatment, and urges people not to attempt self-medication with probiotics and other methods to alter the diversity of their gut bacteria.

“They may not help their situation and could potentially harm themselves,” she says. “Given that treating the microbiome would be a completely new approach, it will be best done in the context of a carefully monitored clinical trial.”

The power of diversity

Researchers took gut microbiome samples from 30 patients who responded to anti-PD1 immune checkpoint blockade drugs and 13 who did not respond. Their findings showed:

- A greater diversity of bacteria in the microbiomes of responders

- Increased abundance of the Ruminococcaceae family of bacteria within the Clostridiales order in responders

- Increased abundance of Bacteriodales in non-responders and a much lower diversity of bacteria