- Diseases

- Acoustic Neuroma (14)

- Adrenal Gland Tumor (24)

- Anal Cancer (66)

- Anemia (2)

- Appendix Cancer (16)

- Bile Duct Cancer (26)

- Bladder Cancer (68)

- Brain Metastases (28)

- Brain Tumor (230)

- Breast Cancer (718)

- Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (2)

- Cancer of Unknown Primary (4)

- Carcinoid Tumor (8)

- Cervical Cancer (154)

- Colon Cancer (164)

- Colorectal Cancer (110)

- Endocrine Tumor (4)

- Esophageal Cancer (42)

- Eye Cancer (36)

- Fallopian Tube Cancer (6)

- Germ Cell Tumor (4)

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (2)

- Head and Neck Cancer (6)

- Kidney Cancer (124)

- Leukemia (344)

- Liver Cancer (50)

- Lung Cancer (288)

- Lymphoma (284)

- Mesothelioma (14)

- Metastasis (30)

- Multiple Myeloma (98)

- Myelodysplastic Syndrome (60)

- Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (4)

- Neuroendocrine Tumors (16)

- Oral Cancer (100)

- Ovarian Cancer (170)

- Pancreatic Cancer (164)

- Parathyroid Disease (2)

- Penile Cancer (14)

- Pituitary Tumor (6)

- Prostate Cancer (144)

- Rectal Cancer (58)

- Renal Medullary Carcinoma (6)

- Salivary Gland Cancer (14)

- Sarcoma (236)

- Skin Cancer (296)

- Skull Base Tumors (56)

- Spinal Tumor (12)

- Stomach Cancer (60)

- Testicular Cancer (28)

- Throat Cancer (90)

- Thymoma (6)

- Thyroid Cancer (98)

- Tonsil Cancer (30)

- Uterine Cancer (78)

- Vaginal Cancer (14)

- Vulvar Cancer (18)

- Cancer Topic

- Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Issues (20)

- Advance Care Planning (10)

- Biostatistics (2)

- Blood Donation (18)

- Bone Health (8)

- COVID-19 (362)

- Cancer Recurrence (120)

- Childhood Cancer Issues (120)

- Clinical Trials (628)

- Complementary Integrative Medicine (24)

- Cytogenetics (2)

- DNA Methylation (4)

- Diagnosis (230)

- Epigenetics (6)

- Fertility (64)

- Follow-up Guidelines (2)

- Health Disparities (14)

- Hereditary Cancer Syndromes (124)

- Immunology (18)

- Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (8)

- Mental Health (118)

- Molecular Diagnostics (8)

- Pain Management (62)

- Palliative Care (8)

- Pathology (10)

- Physical Therapy (18)

- Pregnancy (18)

- Prevention (898)

- Research (392)

- Second Opinion (74)

- Sexuality (16)

- Side Effects (604)

- Sleep Disorders (10)

- Stem Cell Transplantation Cellular Therapy (216)

- Support (404)

- Survivorship (322)

- Symptoms (184)

- Treatment (1776)

High-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma survivor defies the odds

5 minute read | Published May 24, 2022

Medically Reviewed | Last reviewed by an MD Anderson Cancer Center medical professional on May 24, 2022

Last updated Feb. 14, 2023

Curtis Crump is serious about staying in shape. With his job, he has to be.

“I’m an airplane and helicopter pilot with the Harris County Sheriff’s Department,” he explains. “I conduct aerial surveillance that helps officers on the ground track down and catch criminals on the run. It’s demanding work, and physical fitness is a requirement.”

But Curtis wasn’t always so healthy. Four years ago, doctors found high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma in his liver, which was presumed to have originated in his colon.

A high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma diagnosis

The first warning came late on a Sunday night. Curtis was driving home to Houston after visiting his then-girlfriend in San Antonio. Halfway home, he developed a stabbing pain in his right side.

“It was agonizing,” he says. “I thought I had appendicitis.”

He pulled into an urgent care center, where a CT scan detected a tumor the size of a tennis ball in his colon.

“After that,” he says, “everything happened quickly.”

An ambulance took Curtis to a nearby hospital, where a biopsy confirmed that he had cancer in his liver, too.

“The doctor told me my liver was saturated with tumors,” Curtis recalls. “When I asked, ‘How many?’ he said, ‘Too many to count.’”

Curtis was given a stage IV high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma diagnosis and six months to live.

A second opinion offers hope

A friend who’s a nurse urged him to seek a second opinion at MD Anderson.

“She said MD Anderson has a track record of fixing what others can’t,” Curtis says. “That’s what I needed – a doctor who wouldn’t give up on me.”

At MD Anderson, Curtis met with Craig Kovitz, M.D.

The doctor didn’t mince words.

“Neuroendocrine tumors are generally low-grade malignancies that are not very aggressive,” explains Kovitz. “We can treat them successfully with a variety of therapies. But high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas are very different. They are highly aggressive from the get-go. And while they often respond to chemotherapy at first, they can become resistant to the drugs that initially seem to help and progress quickly.”

Curtis understood.

“I knew there were no guarantees,” he says, “but we had to try.”

Dealing with depression after a high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma diagnosis

Curtis began treatment in November 2017 with eight rounds of two chemotherapy drugs – carboplatin and etoposide.

“It was rough,” Curtis says, “not only because of the toll chemotherapy took on my body, but also because I was depressed. That can happen with a diagnosis like mine.”

For two weeks, he lay in bed. He stared at the ceiling, unable to sleep. He lost his appetite. His girlfriend left him.

Then, he suddenly snapped out of it.

“I jumped out of bed and told myself, ‘If I’m going down, it won’t be without a fight.’”

Curtis returned to the gym and worked out three hours every day – even on the days he received chemotherapy.

“I’ve always exercised regularly, but I went into overdrive,” he says. “I didn’t want cancer to make me look frail.”

He began attending weekly church services and got baptized.

And he went back to work.

“Dr. Kovitz advised me to stop flying until chemotherapy was over, so I handled desk duties instead,” he explains. “The tumor in my colon was still large enough to perforate my bowel. If that happened while I was in the air, well … I’d be in some serious trouble.”

High-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma surgery and a cancer recurrence

By the time Curtis finished chemotherapy in March 2018, his tumors had stopped growing. Some had even shrunk or disappeared.

He was now stable enough to undergo surgery. Colon and rectal surgeon Craig Messick, M.D., removed the residual tumor in Curtis’ large intestine.

With the colon tumor gone and the liver tumors’ growth on hold, Curtis enjoyed a four-month respite from treatment.

Then, the liver tumors began to multiply.

An immunotherapy clinical trial for neuroendocrine tumors

Kovitz prescribed two different chemotherapy regimens over the next six months to shrink the tumors in Curtis’ liver. One worked briefly, and one not at all.

With the cancer spreading and his options dwindling, it was time for Curtis to try something different.

“When standard treatments stop working,” Kovitz explains, “the next step is a clinical trial.”

He referred Curtis to MD Anderson’s Clinical Center for Targeted Therapy, where researchers test experimental drugs and drug combinations so new that they are not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

One of those clinical trials, led by Apostolia M. Tsimberidou, M.D., Ph.D., was testing a combination of two immunotherapy drugs – nivolumab and ipilimumab – for the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors.

Unlike chemotherapy that directly destroys cancer cells, immunotherapy trains a patient’s own natural immune system to identify, target and eliminate cancer cells.

“Because these immunotherapy drugs had created prolonged clinical responses and improved overall survival in a number of different tumor types, we hypothesized that they might boost patients’ immune systems to eliminate high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas as well,” explains Tsimberidou.

No signs of neuroendocrine carcinomas after clinical trial

Three months after he joined the clinical trial, Curtis’ tumors had shrunk by 65%. In another three months, they’d shrunk by 80%.

“I was hoping the immunotherapy would slow down my cancer’s growth and buy me more time,” he says. “But I got much more than I’d hoped for.”

Nine months after Curtis joined the clinical trial, a CT scan detected no evidence of tumors, and a biopsy found no cancer cells in his liver.

“The doctors said I had a complete response,” Curtis says, “which means all signs of the disease had disappeared.”

Two years have passed since Curtis completed the trial. He still shows no signs or symptoms of cancer.

“Immunotherapy can provide long-term protection against cancer, because it trains the immune system to recognize and remember what cancer cells look like,” Tsimberidou explains. “This immune ‘memory’ can last for decades after treatment is completed.”

Life after high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma treatment

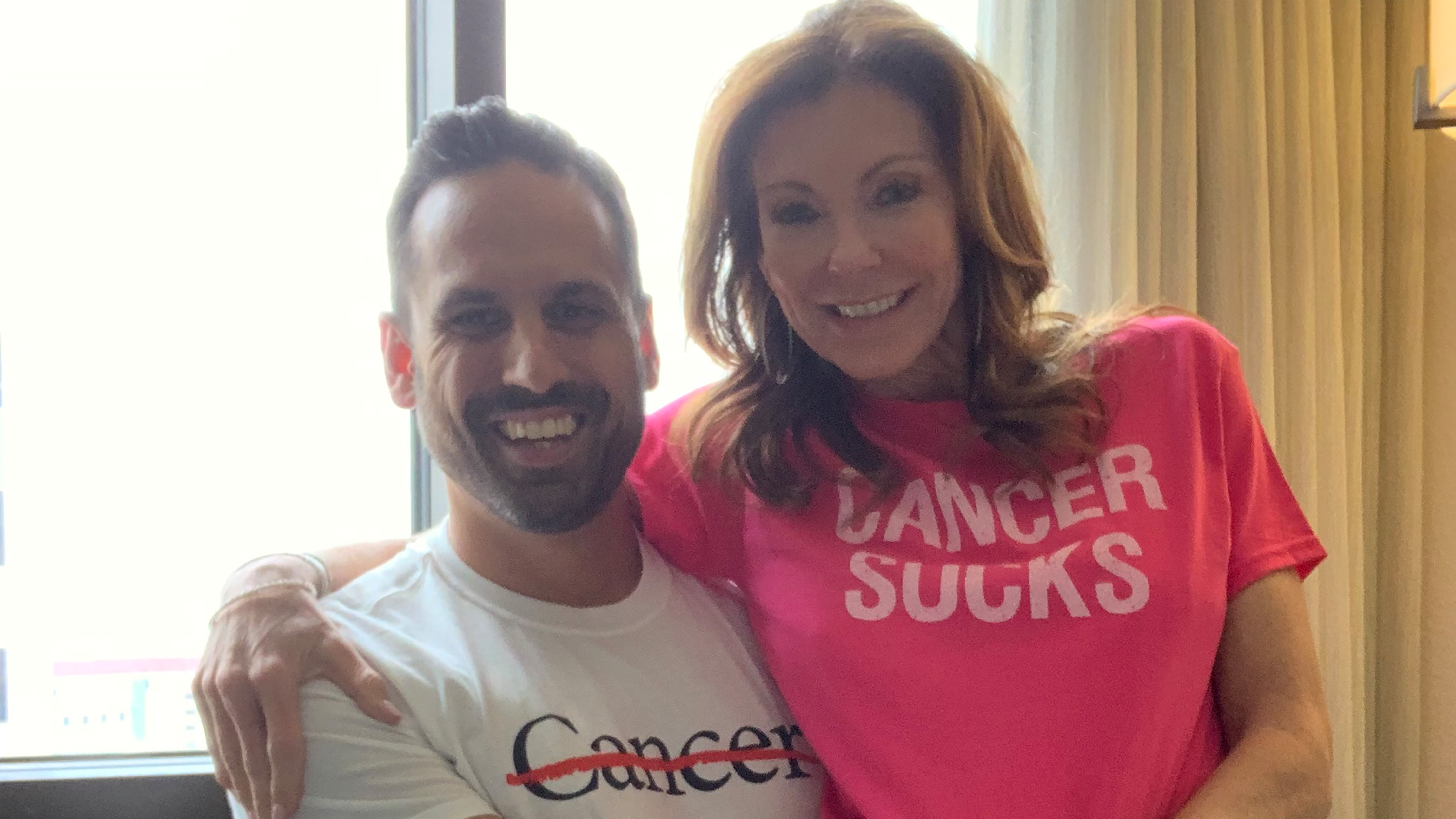

Today, Curtis is back in the air and flying high. He’s been promoted from deputy to sergeant. He has a new girlfriend, a new house and a new offshore fishing boat. When he’s not working, he’s in the gym or at the beach. Life is good.

“I have a lot to be thankful for,” he says. “MD Anderson changed my prognosis from cancer patient to survivor.”

He offers this advice to others facing a challenging diagnosis: "Never give up, and don't accept the first prognosis you receive. I was given six months to live. Then I came to MD Anderson, and look at me now."

Request an appointment at MD Anderson online or by calling 1-855-895-3844.

I was given six months to live. Then I came to MD Anderson, and look at me now.

Curtis Crump

Survivor