The drug that may make chemo a thing of the past

FDA-approved ibrutinib is helping chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients forget they have the disease

Looking for an answer to his worsening chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that didn’t involve chemotherapy, Phoenix cardiologist Marvin Padnick came to MD Anderson at his wife’s suggestion in 2012.

“There was one last opening in a clinical trial of ibrutinib,” he recalls. “Fortunately for me.”

At the time, ibrutinib was a promising experimental targeted therapy for CLL, a cancer of the white blood cells that has been treated with some success by combining chemotherapy and the antibody rituximab.

“For me, ibrutinib is a miracle drug that saved my life. I don’t believe I would have survived another round of chemotherapy,” says Padnick, 69, now director of cardiology at an Oklahoma hospital.

Having exchanged the discomfort and fear of advanced CLL for a regimen that includes running 3-6 miles daily on a treadmill and busy, gratifying days at work, the fact that Padnick is a cancer patient has slipped to the back of his mind.

“I forget I have this disease,” he says via phone on his way to pick up his wife, Dee, for a dinner date. “The only reminder is when I go to MD Anderson every three months for routine blood work.” That and the three capsules of ibrutinib he takes daily.

Now, more patients have that option. In February, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted accelerated approval of the drug, now called Imbruvica, for previously treated CLL patients.

Click on the image to learn "Jan Burger, M.D., Ph.D., and Susan O’Brien, M.D.,

explain advances in CLL treatment (part 1)"

An exciting time for CLL treatment

“Ibrutinib produces durable responses in patients after other treatments have failed, and with very little toxicity. The main side effect is mild diarrhea that usually resolves over time,” says Susan O’Brien, M.D., who led the phase I clinical trial of the drug.

O’Brien, a professor in Leukemia, and MD Anderson colleagues were instrumental in bringing the drug, developed by Pharmacyclics, Inc., to clinical trial and helped solve a puzzle about ibrutinib’s initial effects, which appeared to be alarming. (More on that later.) Today they continue advanced clinical trials, including a combination trial through MD Anderson’s Moon Shots Program.

“This is an exciting time for CLL, with ibrutinib and other drugs in clinical trials providing new approaches that move us away from reliance on chemotherapy combinations,” O’Brien says.

One important advantage is that ibrutinib does not suppress bone marrow production of normal blood cells such as red cells, platelets and infection-fighting white cells. CLL already does that, exposing patients to potentially lethal infections and to bleeding. Chemo also can worsen this effect, known as myelosuppression.

Even successful drug regimens such as the fludarabinecyclophosphamide-rituximab (FCR) combination, developed at MD Anderson and now considered the CLL standard of care, can be difficult for older patients to tolerate. Chemo also raises a patient’s risk of developing other cancers later on.

“Our goal now is to eliminate the need for chemo in treating CLL,” says Michael Keating, M.D., professor in Leukemia and a pioneer in treatment of the disease.

CLL — the most common adult leukemia — is a malignancy of immune system B cells (white blood cells that normally produce antibodies against infection). The American Cancer Society estimates 15,720 new cases will be diagnosed in 2014, and about 4,600 people will die of CLL.

Ibrutinib blocks Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), a vital component of B cell receptor signaling. In doing so, it disrupts a number of molecular signaling networks that are important for the survival and growth of CLL cells.

Click on the image to learn Jan Burger, M.D., Ph.D., and Susan O’Brien, M.D.,

explain advances in CLL treatment (part2)

High response rates, low disease progression

In December, O’Brien reported on a clinical trial involving 140 CLL patients that showed ibrutinib alone produces complete or partial responses in 88% of those who have had previous treatment, and 86% who have received the drug as initial therapy. At the 30-month mark, 76% remained on the drug and showed no sign of the disease progressing.

Combining the drug with the antibody rituximab boosted the response rate to 95% in a clinical trial led by Jan Burger, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor in Leukemia and Padnick’s oncologist. At 18 months, 78% of a 40-patient group showed no progression.

Click on the image to see Jan Burger, M.D., Ph.D.,

and Susan O’Brien, M.D., explain advances in

CLL treatment. (part two of two)

Driving CLL cells out of hiding

CLL develops slowly and often is monitored for years before high white blood cell counts and other indicators point to the need for treatment.

Alarmingly, patients who enrolled early in the phase I trial showed an increase in their white blood cell counts after taking ibrutinib. “That’s normally a sign of disease progression that would result in the patient being taken off the drug,” O’Brien says.

But there were offsetting clinical observations that discouraged jumping to conclusions.

“CLL cells accumulate in the lymph nodes, so these patients have a lot of swelling, especially around the neck,” O’Brien explains. Just as the white cell counts rose, bloated lymph nodes began to retreat and patients reported feeling better. Eventually, white cell counts began to fall.

Burger conducted laboratory studies that illuminated what was going on.

“Ibrutinib flushes the leukemia cells out of the bone marrow, lymph node and spleen and into the bloodstream, where they lose the support they get from surrounding tissue and slowly die,” Burger says. “CLL cells generally are long-lived, even without survival signals.”

Click on the image to see Jan Burger, M.D., Ph.D., and Susan O’Brien, M.D.,

discuss advances in CLL treatment.

Rapid response

It can take months for blood counts and bone marrow involvement to return to normal as the interrupted growth signaling caused by ibrutinib slowly takes its toll. Some patients who lack certain genetic mutations in their CLL cells respond more rapidly. Padnick, apparently, is one of them.

“My spleen was larger than ever when I started ibrutinib, and within a week it started to shrink, and in a month I couldn’t feel it at all,” Padnick says. “My white blood cell count went from 150,000 to 5,000 (normal) in a month. I had no side effects and didn’t miss a day of work during treatment.”

This was a stark contrast to his experience in Arizona with a chemotherapy combination, which knocked him out of work for three months and resulted in hospitalization at one point because of an allergic reaction to one of the drugs.

Looking like a weightlifter on steroids

Patients such as Bob White may never know what it’s like to be on a chemotherapy/rituximab combination.

The retired petroleum engineer from the Fort Worth area went straight into the arm of the phase II trial that was added for previously untreated patients after the strong results for those previously treated.

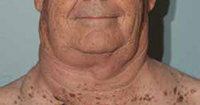

“My lymph nodes were so swollen I couldn’t button a size 19 shirt, and I normally wear a 17. I looked like a weightlifter who had been on way too many steroids,” White recalls, referring to when he started ibrutinib in 2011.

His experience was more typical than that of Padnick. White’s whitecell count shot from 60,000 to 100,000 per cubic milliliter of blood, but within two weeks his lymph nodes began to shrink and soften. He had some fatigue caused by low red blood cell counts and some diarrhea, which he chased away with Imodium.

By October, his anemia subsided as his white blood cell counts fell. By spring 2012, his counts were normal, and by the fall of 2013, CLL cells were only detectable in 4% of his bone marrow — down from 40%.

“It took about six months, but for a patient like me, who was in otherwise good health, taking the drug itself is just fine, even if it takes it six months or a year to really do its thing,” White says.

CLL Moon Shot advances the cause

So far, ibrutinib has led to few complete remissions. The drug tamps down CLL, but so far doesn’t cure it, Burger reports. However, complete response rates are increasing in the group of patients taking the ibrutinib/rituximab combination. O’Brien suspects that, over time, more complete remissions will emerge as the ibrutinib slowly destroys CLL cells and patients are followed longer.

New drugs are in the pipeline. Idelalisib blocks a different molecular pathway called PI3K. O’Brien co-led a clinical trial of the drug combined with rituximab, compared with rituximab alone, for heavily pretreated CLL patients who weren’t eligible for chemotherapy combinations.

The combination was so superior that the clinical trial was halted in October after an early data analysis.

CLL was chosen as one of MD Anderson’s moon shots, a program to dramatically reduce cancer deaths. Burger leads a new combination trial launched in December that compares ibrutinib to ibrutinib plus rituximab in 208 previously treated CLL patients.

Genomic analyses of patients’ CLL cells will be done before and during treatment and at the point of resistance, when it develops, to reveal how the disease changes during treatment.

Burger and colleagues are trying to stay ahead of CLL by studying cases where the leukemia became resistant to ibrutinib. “We’ll need to identify and understand these mechanisms so we can develop ways to defeat resistance as it arises.”

Before

“My lymph nodes were so swollen I couldn’t button a size 19 shirt,” says CLL patient Bob White, a retired petroleum engineer.

After

White was treated with ibrutinib and didn’t undergo chemotherapy.