Curb smoking and tobacco use to combat lung cancer

Going toe-to-toe with tobacco

Fifty years ago, the surgeon general’s first report on smoking was published. Since then, MD Anderson has been steadfast in its fight to help people kick the habit and treat those who’ve developed cancer caused by smoking and secondhand smoke.

MD Anderson isn’t pulling any punches in its fight to put smoking down for the count

Smoking reached the height of its popularity in the United States in the mid-1950s. In those days, it was considered something of a national pastime, like baseball. In fact, stars of the game such as Mickey Mantle, Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams and Willie Mays all appeared in cigarette ads.

As early as 1951, research in Great Britain tied smoking to lung cancer, yet it was still seen by many as a glamorous, sophisticated, even harmless, thing to do. And it was inescapable. People smoked everywhere — on airplanes and subways; in offices, sports stadiums, movie theaters and hospitals; as well as in their homes, unknowingly exposing loved ones to harmful secondhand smoke.

Tobacco companies such as R.J. Reynolds countered growing concern about the dangers of smoking with ads for Camel brand cigarettes featuring the tagline “More doctors smoke Camels.” Other ads included professional athletes claiming “They don’t get your wind.”

But the smoke screen dispersed in 1964 with the release of the first Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health. The landmark document, informed by more than 7,000 scientific articles, definitively linked smoking to lung cancer and other pulmonary diseases. In the words of then-U.S. Surgeon General Terry Luther, M.D., the report “hit the country like a bombshell. It was front page news and a lead story on every radio and television station in the (nation).” And it snapped the country to attention about the dangers of combustible tobacco.

“There’s been no other government action taken that has impacted tobacco control more than the release of the first U.S. surgeon general’s report,” says Ernest Hawk, M.D., vice president of MD Anderson’s Cancer Prevention and Population Sciences. The division is dedicated to eliminating cancer health disparities through research, patient care, education and control.

Some, such as Harvard historian Allan Brandt, contend the reverberations of the report’s impact have been felt far beyond smoking. Brandt told National Public Radio earlier this year, “If we look at the history of public health — from the safety of cars and roads, other dangerous products, the environment, clean air, the workplace — all of these issues really have their origins in a moment 50 years ago around the first surgeon general’s report.”

Luther convened a panel of medical academics to prepare the document. Its youngest member, Charles LeMaistre, M.D., later went on to serve as MD Anderson’s second full-time president (1978-1996). LeMaistre and his colleagues revealed the startling reality of smoking’s harmful effects at a time when nearly 45% of the population smoked.

The report linked smoking to 11 different types of cancer, chronic lung disease and heart disease. Today, it’s associated with 15 different cancers, including liver and colorectal cancers, which were added to the list in the 2014 version, the Health Consequences of Smoking — 50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General.

Back in 1964, the report sparked debate and led to progressive action. Alerted to the dangers of tobacco, public opinion was swayed. Its details revealed the need for a cultural transformation among a population that for decades was socially encouraged to smoke. When reality set in, public policy was spawned and the slow but steady progression toward ending tobacco began.

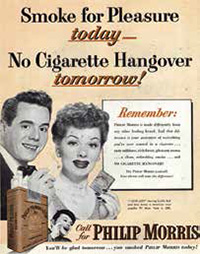

In the past, tobacco companies employed

marketing tactics that included paying

celebrities such as “I Love Lucy” stars

Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball to endorse

their cigarettes.

credit: trinketsandtrash

Within months of its release, the Federal Trade Commission ordered tobacco companies to place a warning label on their products. By 1970, President Richard Nixon had signed the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act, banning all television and radio cigarette advertisements.

Bold advances in tobacco control

Over the years, there’s been a long line of victories and milestones in tobacco control. A recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association estimated 8 million U.S. lives have been saved through efforts that were a direct result of the first report.

Actions such as the 2010 Affordable Care Act have helped remove barriers to tobacco users by eliminating co-pays for screening services and expanding tobacco cessation benefits. The act also established the Prevention and Public Health Fund to prevent and reduce tobacco use. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently updated regulations restricting the sale and distribution of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco to children and adolescents, making tobacco products less accessible to minors.

In February, the FDA launched “The Real Cost,” a five-year, $600 million national public education campaign to prevent tobacco use among minors. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released an updated edition of its guide to Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs to help states develop more effective tobacco programs.

Also on the heels of the 50-year progress report, one of the largest drugstore chains in America, CVS Caremark, announced in February its plan to eliminate the sale of tobacco in its 7,600 stores by Oct. 1.

“We hope other retailers will take similar actions,” Hawk says. “Our goal is to ensure people stop smoking, make sure kids don’t start and make tobacco less attractive to everyone. Actions like this are a good start.”

Leading the effort

Ellen R. Gritz, Ph.D., chair of Behavioral Science at MD Anderson, has played a role in many major tobacco milestones. Gritz, who contributed to the 1980 Surgeon General’s Report on Women and Smoking, explains that over the years MD Anderson has mirrored the high standards set by the report through the institution’s tobacco control efforts.

“We have a profound tobacco cessation program available free to patients, employees and their families,” Gritz says. “We also are targeting children, adolescents and young adults through tobacco prevention programs and mobile apps designed specifically for the young.”

In 1989, MD Anderson was one of the first hospitals to become smoke-free. The institution has developed multidisciplinary care to treat lung cancer patients and established programs to combat the disease and other cancers associated with smoking.

In addition, it has focused research on discovering the best ways to help people quit smoking or never begin in the first place. Last year, the institution’s behavioral scientists developed and released Tobacco-Free Teens, an app designed to help teenagers.

Researchers are taking anti-smoking programs into schools and into the community, zeroing in on “at risk” populations such as the underserved and mentally ill, while collaborating with other health care systems and policy makers. The institution’s combined efforts through the Cancer Prevention and Control Platform support MD Anderson’s Moon Shots Program — an aggressive 10-year push to drastically decrease cancer deaths. (The importance of tobacco control in the Moon Shots Program)

Later this year, prevention leaders will hold the first Texas Tobacco Summit with plans to announce EndTobacco, a comprehensive initiative to combat tobacco use. Through actions in policy, education and community services, the program potentially will help eliminate tobacco use in organizations and communities across Texas, the nation and around the world.

What still needs to be done

Even with the noted successes in tobacco control over the years, smoking continues to be the leading cause of preventable death in the U.S. Tobacco is linked to 87% of lung cancer deaths and one in three cancer deaths. Each year, 70% of smokers attempt to quit (see “It’s quitting time”).

“More than 40 million people still smoke in this country, and that’s a problem,” says Lewis Foxhall, M.D., vice president for Health Policy at MD Anderson. “Although we’ve seen a lot of movement recently and over the years in tobacco control, there’s still much work to do.”

MD Anderson has made tobacco control an institutional public health priority with renewed efforts. According to Gritz, winning the battle necessitates an investment in basic, clinical and population-based research commensurate with the economic, medical and societal burden of diseases caused by tobacco use.

“We need targeted research to improve and refine prevention approaches for children and youth. We need pharmacologic and behavioral interventions promoting tobacco cessation with an increased, more uniform access and application in health care ,” Gritz says. “Research on other underserved groups and populations also is critical.”

We've come a long way, baby.

1964

Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service is published. The report, the surgeon general’s first on smoking, concludes smoking cigarettes causes lung cancer and other diseases. Charles LeMaistre, M.D., president of MD Anderson from 1978-1996, served on the advisory committee.

1966

In response to congressional legislation, health warnings are printed on cigarette packs that read, “Caution: Cigarette Smoking May Be Hazardous to Your Health.”

1970

Congress passes legislation banning radio and television cigarette advertising.

1972

Environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) is identified as a health risk to nonsmokers in the Surgeon General’s The Health Consequences of Smoking.

1975

The Minnesota Clean Indoor Air Act, which requires designated smoking areas in public places, takes effect.

The Army and Navy stop including cigarettes in service members’ rations.

1980

MD Anderson’s Ellen R. Gritz, Ph.D., contributes to the Surgeon General’s Report on Women and Smoking.

1981

LeMaistre serves as chair of the National Conference on Smoking or Health.

1985

LeMaistre serves as chair of the International Summit of Smoking Control Leaders.

1986

LeMaistre serves as president of the American Cancer Society.

1988

A ban on smoking aboard commercial airline flights lasting two hours or less takes effect.

The surgeon general concludes that nicotine is addictive in The Health Consequences of Smoking: Nicotine Addiction.

1990

Smoking on all domestic flights is banned.

1992

ETS is classified as a “Group A” carcinogen by the Environmental Protection Agency.

1993

Smoking is banned in the White House.

1994

MD Anderson becomes one of the few U.S. academic medical centers to adopt a policy prohibiting the receipt of tobacco money for research funding.Mississippi sues the tobacco industry to recover Medicaid costs for tobacco-related illnesses.

1996

Texas sues the tobacco industry in Federal court. MD Anderson tobacco experts advise the state attorney general.

2000

Funds from the National Cancer Institute and the George and Barbara Bush Endowment for Innovative Cancer Research help MD Anderson establish ASPIRE (A Smoking Prevention Interactive Experience). ASPIRE is an evidencebased, multimedia tobacco prevention and cessation program for middle and high school students.

2006

MD Anderson launches the Tobacco Treatment Program, a free tobacco cessation program for patients and their family members, with funding from the Texas Settlement Lawsuit.

2007

MD Anderson joins the Smokefree Houston Coalition, which results in the passing of an ordinance to make all Houston workplaces and public spaces smoke-free.

2008

MD Anderson establishes the Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk to study how to predict and reduce cancer risk. Tobacco research is a major focus of the institute.

2009

President Obama signs legislation granting the FDA regulatory authority over tobacco products.

2010

Marketing restrictions on tobacco products take effect, specifically for those targeting youth. Cigarette companies are prohibited from using “light,” “low” and other misleading health descriptors.

President Obama signs legislation that includes provisions to expand tobacco cessation benefits and establishes the Prevention and Public Health Fund to prevent and reduce tobacco use.

2012

Launch of the Moon Shots Program, an unprecedented effort to dramatically accelerate scientific discoveries into clinical advances that reduce cancer deaths. Lung cancer is one of the initial cancers targeted by the program.