Surgically removing cancer risk

For Denise Megarity, the decision to have her ovaries removed at a young age — and thereby dramatically reduce her risk of multiple cancers — was an empowering one

Her mother, Margarita Wight, is a cancer warrior. First diagnosed with breast cancer in 1987, she’s survived the disease three times. Seven years ago, Wight was diagnosed with ovarian cancer — and again beat the odds.

In fact, Megarity and Wight’s family tree is dotted with cancer caused by a defective gene.

“Looking back at our family history on my mother’s side, there are all kinds of cancer associated with the BRCA genes,” explains Megarity. “My mother’s father died of pancreatic cancer. My mother’s first cousin had male breast cancer, and his daughter had breast cancer, too. And my first cousin was diagnosed with breast cancer when she was just 27.”

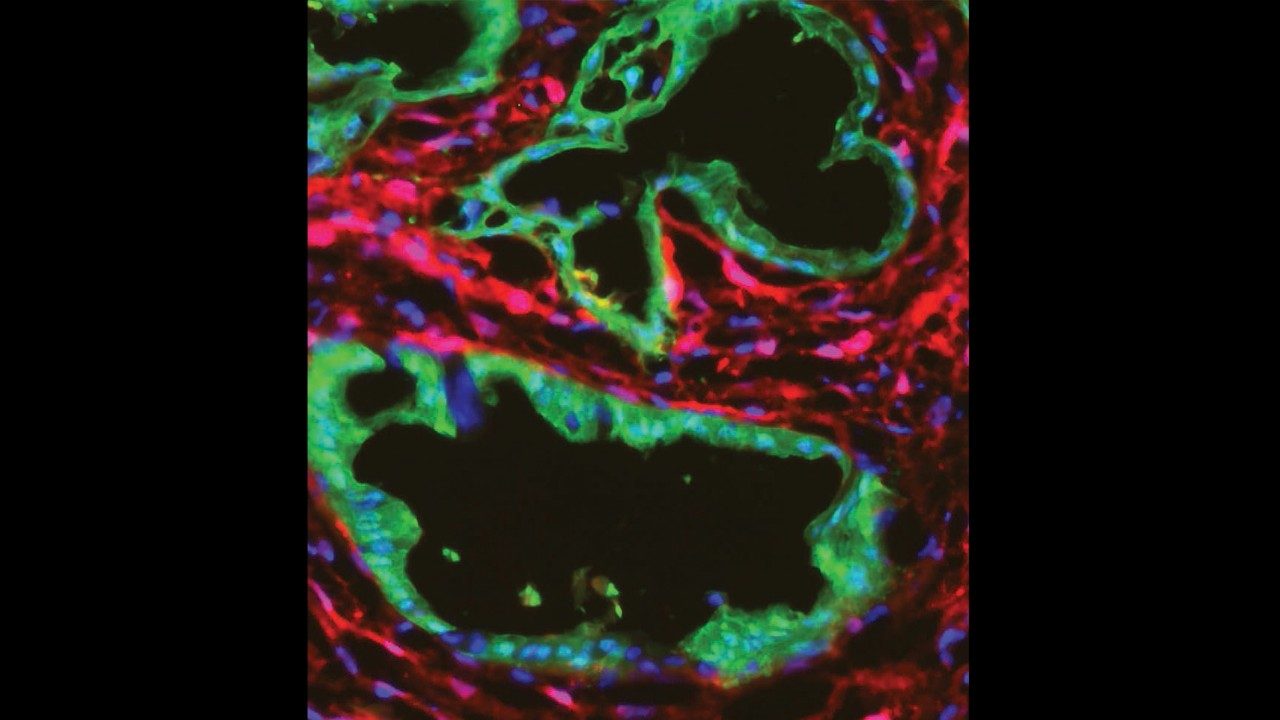

BRCA genes repair damaged cells and make sure they grow normally. But the mutation of tumor suppressor genes BRCA1 or BRCA2 is associated with a hereditary risk for both breast and ovarian cancers, as well as other cancers. According to the American Cancer Society, approximately 50 to 65% of women with either BRCA mutation will develop breast cancer, and 35 to 45% will develop ovarian cancer before the age of 70.

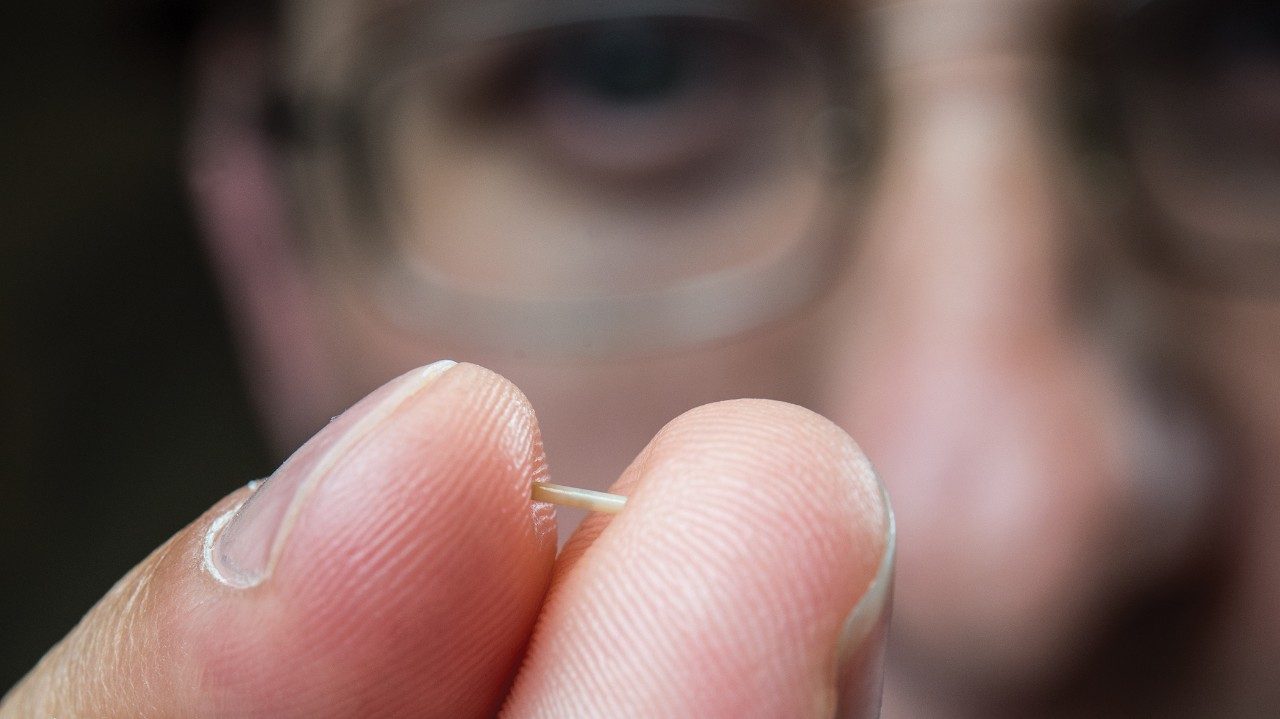

Initially, Megarity’s mother didn’t conclusively test positive for BRCA abnormalities — leaving the mother-daughter duo and their MD Anderson physicians puzzled. Years later, when Wight was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, a follow-up test uncovered the BRCA1 mutation. Immediately, her daughter made the decision to undergo genetic testing. Like her mother, Megarity carried the BRCA1 mutation. At 42, Denise opted to undergo an oophorectomy to remove her ovaries.

A recent study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology may encourage women even younger than Megarity with either BRCA mutation to strongly consider undergoing preventive surgeries.

The international registry study followed nearly 5,800 women with either BRCA mutation for as long as 19 years and found that those who had the oophorectomy reduced their risk of ovarian and other gynecological cancers by 80%. They also cut their risk of dying by age 70 from any cause by 77%.

The most striking survival benefit was found in women with a BRCA1 mutation who underwent an oophorectomy before the age of 35. The surgery dropped their risk for ovarian cancer to 1% — on par with the risk of women who don’t have the gene mutation. The researchers found that women with an abnormal BRCA2 could wait longer and still achieve the same benefit.

In addition, the research found that women more than doubled their chance of developing ovarian cancer if they opted for the surgery after age 40; they also were at an increased risk for breast cancer.

“As clinicians, we really struggle with the conversation about when is the right time for women with BRCA mutations to remove their ovaries,” explains Shannon Westin, M.D., assistant professor in Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine. “This is a patient population that’s incredibly knowledgeable about its risk and is faced with a very personal decision.”

Also, before this study, there were concerns about removing the ovaries too early because of possible co-morbidities and the known side effects associated with the surgery.

“Yet the study’s overwhelming survival benefit for women with both BRCA1 and 2 mutations should make us more confident that if you have cause — and BRCA is certainly considered cause — then surgery at a young age is beyond appropriate,” Westin says.

National organizations currently recommend that women with BRCA mutations remove their ovaries at age 35, or after completion of childbearing, says Westin. While she isn’t sure this research will amend those recommendations, the study conclusively finds that, for women with BRCA abnormalities, earlier is better.

And while, as a society, women are waiting longer to have children, Terri Woodard, M.D., assistant professor in Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, hopes that recent advances in fertility treatment will help quell the concerns of those with BRCA mutations struggling to balance their desire to have a family with their decision to proceed with the surgery.

“Now, younger women can move forward with their surgery, but first take steps to preserve their ability to have children,” says Woodard, a reproductive endocrinologist and director of MD Anderson’s Oncofertility Consult Service.

“If they’re not partnered, women with BRCA may choose to freeze their eggs prior to their oophorectomy. Or, if they’re married, perhaps they’ll opt to freeze embryos. It’s important for these women to know that they do have options for family planning.”

For Megarity, the decision to undergo an oophorectomy wasn’t overly difficult. A mother to three boys, she and her husband had completed their family.

“While there was a feeling of finality that I dealt with, having the surgery definitely has eased my worry and allowed me to be at peace knowing that I’ve taken steps to decrease my personal cancer risk.”

Carriers of mutated BRCA genes face the difficult decision of if and when to have preventive surgery.

The risks of carrying a mutation

- Both men and women with mutations of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene have an increased risk of breast cancer.

- BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for 20 to 25% of hereditary breast cancers and 5 to 10% of all breast cancer, as well as 15% of ovarian cancers.

- The mutation can come from the mother or father. A child of a parent with the mutation has a 50% chance of inheriting it.

Other cancers linked to the mutations:

- Women with BRCA1 mutations have an increased risk of developing fallopian tube and peritoneal cancers.

- BRCA2 mutations and, to a lesser extent, BRCA1 mutations raise a man’s risk of breast cancer.

- Both mutations increase a man’s risk of prostate cancer.

- Both men and women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations may be at a higher risk of pancreatic cancer.