Related story: The immuno man

The next step was to identify the genes responsible for the T cell antigen receptor, and, at the time, MD Anderson simply wasn’t equipped for such research. Allison took a visiting professorship at Stanford in the lab of Irv Weisman, a leading scientist who once gave a speech at MD Anderson that had set Allison’s mind abuzz with research possibilities.

As it happened, other scientists beat them to the genes. While in the Bay Area, Allison gave an invited talk at the University of California, Berkeley, and made a strong impression. He was soon recruited to lead the immunology department there.

Leaving MD Anderson in 1984 was difficult.

“Smithville was wonderful for several reasons,” Allison recalls. “I had no administrative duties, I didn’t teach, I just did science all of the time. Had a great team, good support and a few National Institutes of Health grants.

“I owned a house and 18 acres in the Lost Pines area close enough to walk through the woods every day to work (the Science Park is located within Buescher State Park) and had a house in Austin.”

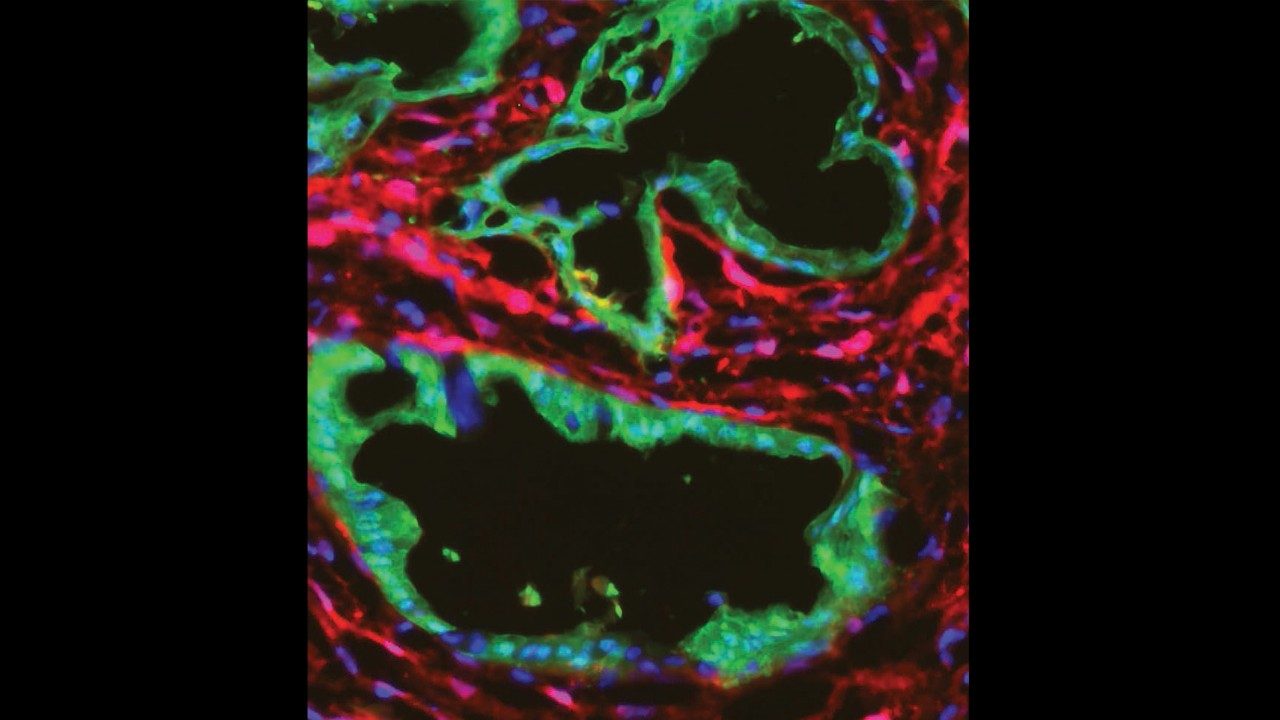

At Berkeley, Allison turned his attention to a molecule on the surface of T cells called CD28. By then, researchers knew that an antigen presented to a T cell was not enough to activate it, and CD28 seemed like a good candidate as a co-stimulatory molecule.

In a study published in Nature, Allison and his colleagues showed that CD28 is cross-linked to the antigen receptor and, when activated, sparks an immune response, much like a gas pedal applied after ignition moves a car.