Related story: The immuno man

French scientists identified another T cell surface protein they named Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4, or CTLA-4. Because it greatly resembled CD28 and was activated by the same binding molecules, the initial thought was that CTLA-4 was another co-stimulator.

Allison’s research, and additional work done by Jeff Bluestone, Ph.D., then at the University of Chicago, indicated otherwise. In July 1994, they presented data at another Gordon Conference showing CTLA-4 inhibited immune responses. Subsequently, they published papers demonstrating that effect in mice.

“CTLA-4 is cross-wired with the antigen receptor and CD28, so the brake is activated at the same time to help ensure that the immune response doesn’t go on and on, destroying healthy cells,” Allison says.

For decades, research had shown that activated T cells often penetrate tumors, indicating an activated immune response, but one insufficient to overcome the cancer. It occurred to Allison that the CTLA-4 checkpoint might be shutting down those immune responses and that blocking it might free T cells to more effectively find and kill cancer.

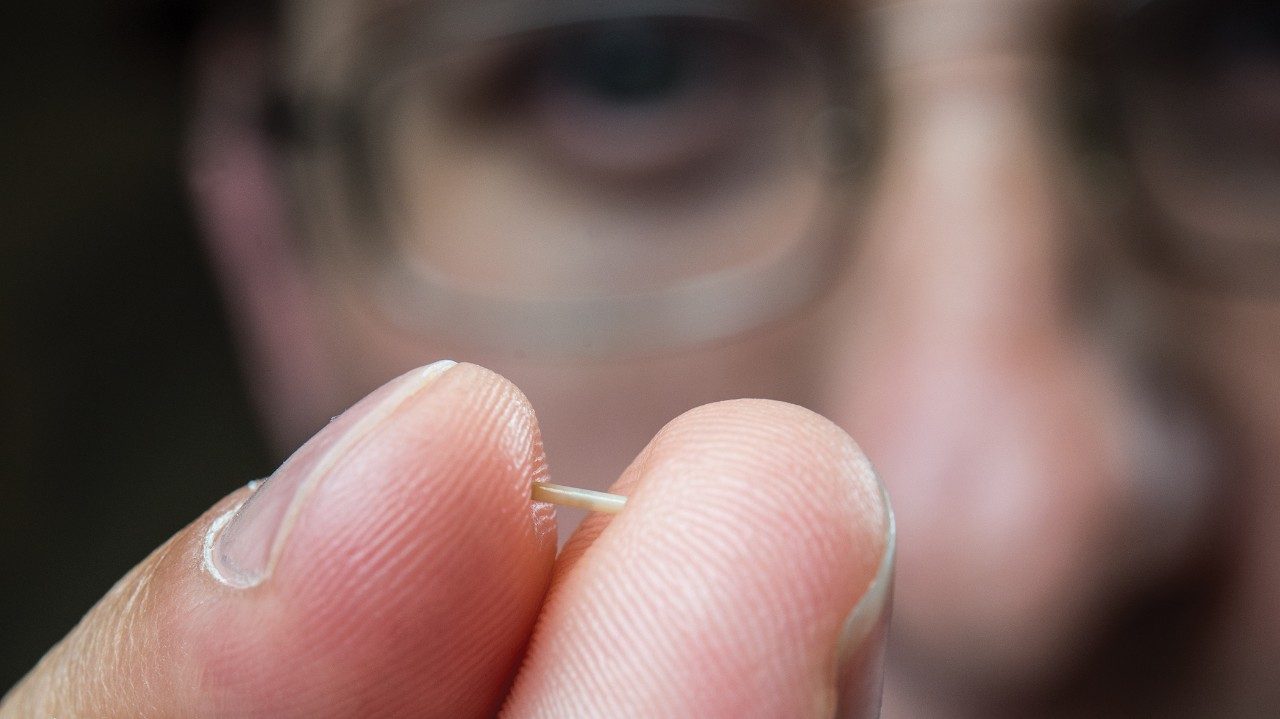

A mouse experiment in 1995 using an antibody against CTLA-4 worked so well that Allison wanted to repeat it immediately. He didn’t know which mice, all with colon cancer, had been treated with the antibody to block CTLA-4. All developed tumors, but by the third week, distinct differences developed. For some, tumor growth slowed, then stopped and the tumors went away completely, while others progressed rapidly.

When the experiment was unblinded after six weeks, nine of the 10 treated mice were fine, all of the untreated had died. These results were repeated in a variety of cancers, including melanoma.

“I thought, ‘we need to get this to people as soon as we can,’ ” Allison says.

Knowledge has been its own reward for Allison, going back to childhood.

“I’ve always wanted to know how things work. My father was a doctor in Alice, Texas, so I had a pretty good look at what it’s like to be a physician. As a doctor, you can’t make mistakes,” says Allison.

“The scientist’s job is to generate and test hypotheses, which are wrong most of the time, otherwise the answer would be obvious. So you go back and do another experiment,” Allison says. “Scientists only need to be right some of the time — preferably about something important.”

Allison has been right often enough about important things that honors have been pouring in — including seven major awards since April 2013.

Prestigious awards given to Allison recently:

- The Economist’s 2013 Innovation Award for Bioscience

- The Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences, which recognizes researchers whose work extends human life and is worth $3 million

- The 2014 Canada Gairdner International Award, which recognizes seminal medical discoveries

- The 2014 Szent-Györgyi Prize for Progress in Cancer Research from the National Foundation for Cancer Research

- The inaugural AACR-CRI Lloyd J. Old Award in Cancer Immunology from the American Association for Cancer Research and the Cancer Research Institute. It’s named in honor of Old, an immunology trailblazer.

- Elected as a fellow of the American Association for Cancer Research Academy

- 2014 Tang Prize for Biopharmaceutical Science