Combating an epidemic

Rising obesity rates spike increase in liver cancer diagnoses

First, the good news: The American Cancer Society reports the overall cancer death rate in the United States has been dropping steadily for 25 years. Now, the bad: Liver cancer isn’t included in this downward trend. Liver cancer rates have more than tripled since the mid-1970s, making it the country’s fastest-growing cause of cancer deaths today.

Why the climactic rise?

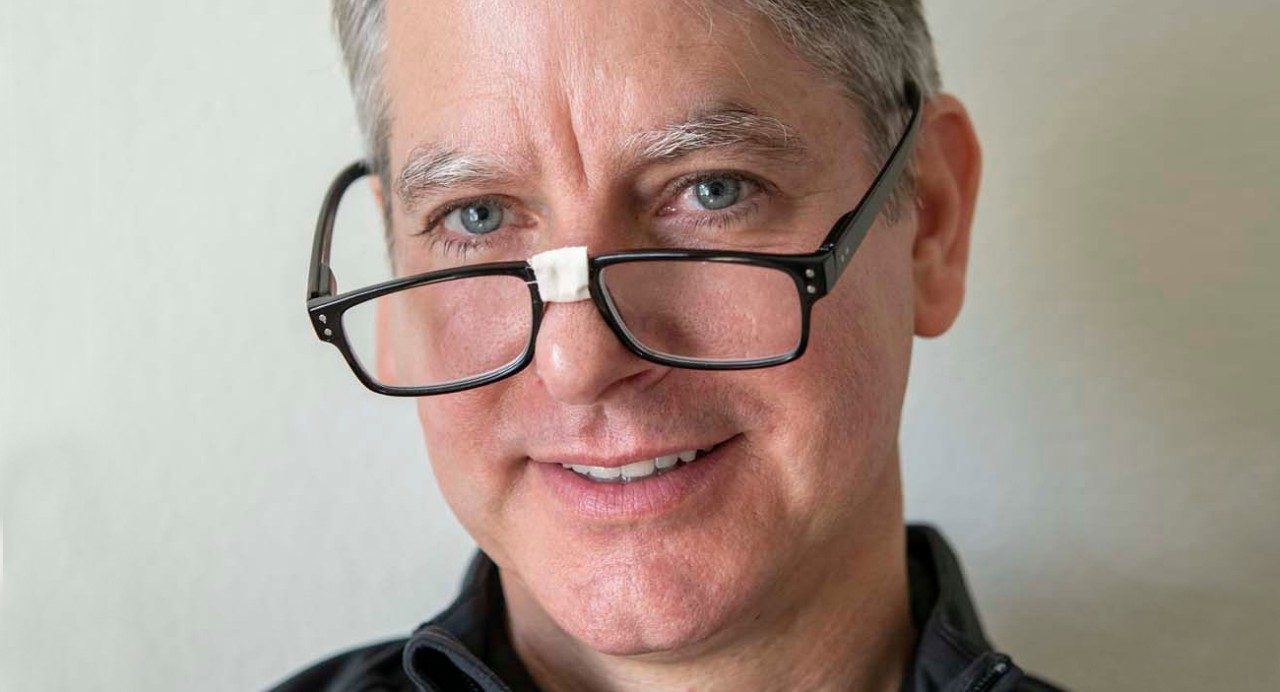

“In the past, liver cancer has been associated with hepatitis B and C virus infections, but that’s changing,” says Darren Sigal, M.D., program director of Gastrointestinal Oncology at Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center in San Diego – a member of the MD Anderson Cancer Network®.

Today, fewer than 5% of liver cancer cases in the United States are caused by hepatitis B, primarily because children have routinely been vaccinated against the virus since 1982. And although there’s no vaccine for hepatitis C, powerful new drugs are curing 90% of patients.

“Viral hepatitis is becoming less important as a cause of liver cancer in the U.S.,” Sigal says.

Obesity-driven disease

Instead, a major culprit behind today’s skyrocketing liver cancer rates is a condition known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Characterized by a buildup of excess fat in the liver, the disease strikes people who drink minimally or not at all (hence “non-alcoholic”). It’s distinctly separate from another type of fatty liver disease caused by alcohol abuse.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is linked to a high-calorie, low-exercise lifestyle.

“Because 70% of American adults are overweight or obese, the nation is experiencing a “tidal wave” of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease cases,” Sigal says, “which in turn is causing record numbers of liver cancer diagnoses.

According to the National Cancer Institute, 30% of Americans have some form of fatty liver disease. That number is poised to reach 50% by 2030.

“In 10 years, half of all Americans will have fatty liver disease,” Sigal explains. “Up to 27% of those fatty liver disease cases will progress to liver cancer.”

Two-drug combination

To combat this epidemic, Sigal is leading a study of a new liver cancer drug that is derived from ocean algae and enlists a patient’s own immune system to attack tumor cells. Developed at Scripps Research in collaboration with the biotechnology company Abivax, the drug, named ABX196, stimulates a type of white blood cell called an invariant natural killer T cell. These cells exist in extremely small numbers in the blood stream, and kill on contact by binding to tumor cells, then releasing a lethal burst of potent chemicals.

“ABX196 is a very unique immune treatment,” Sigal says. “It’s available nowhere else outside this study.”

Participants may enroll at the main trial site at Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center in San Diego, or at the trial’s secondary site at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

In the clinical trial, patients receive ABX196 in combination with an existing drug named nivolumab (brand name Opdivo).

“Sometimes, cancer cells are able to disguise themselves from cancer-killing T cells. If this happens, the cancer cells inactivate the T cells to prevent them from attacking,” explains Ahmed Kaseb, M.D., associate professor of GI Medical Oncology at MD Anderson in Houston and leader of the Houston study site. “Opdivo blocks cancer’s ability to disguise itself, which allows T cells to be active and attack.”

Opdivo alone is highly effective in combating some cancers, particularly lung cancer. But the drug works in only about 15% of liver cancer patients, and even then, only lasts about four months.

“By adding ABX196 to the treatment mix along with Opdivo, this new clinical trial is designed to make Opdivo more effective,” Kaseb explains. “The goal is to see if the synergy between these two drugs can lead to improved outcomes for patients with this deadly cancer.”

Helping those who need it most

Previous tests over the last two years confirmed the therapy worked to activate the immune systems of mice and healthy humans. Now the two-drug regimen is being tested in patients with liver cancer, which carries a particularly grim prognosis.

The five-year survival rate for people with localized liver cancer is 30%, and for those with advanced disease, it’s a dismal 3%.

“Liver cancer is not often found early, because signs and symptoms usually don’t appear until the disease is in its later stages,” Kaseb says. “We very much need a treatment that works.”