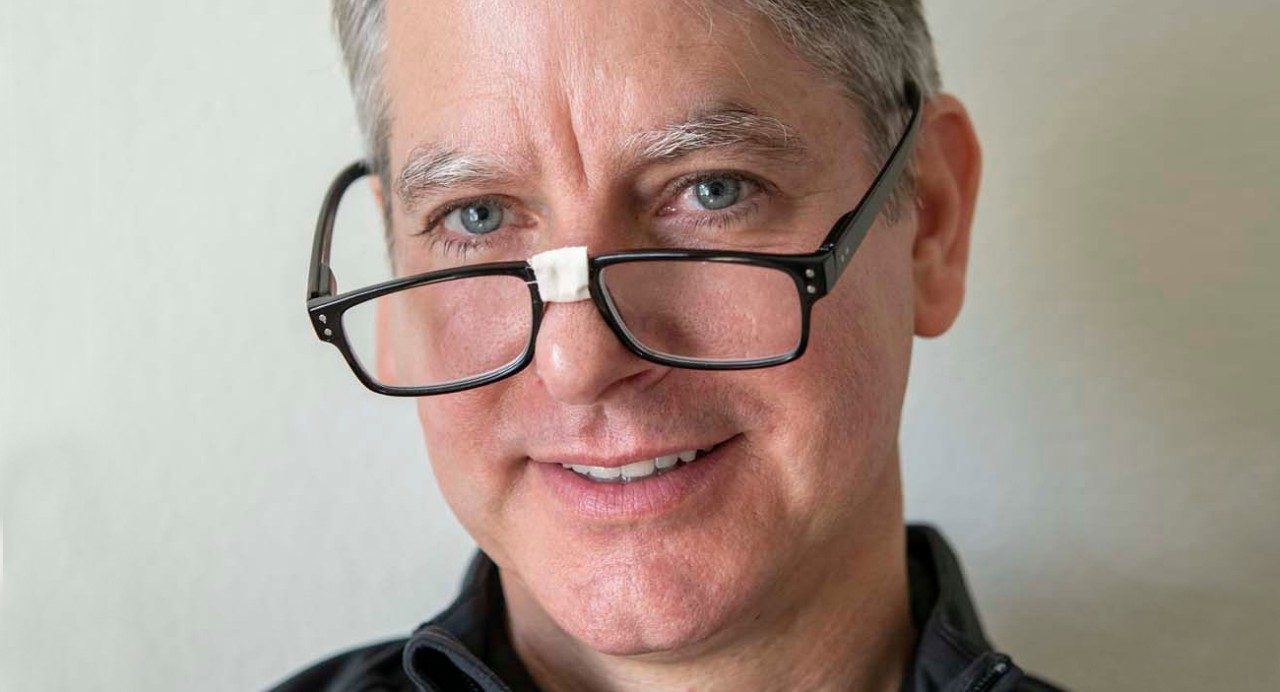

NASA doctor receives personalized leukemia treatment

After 30 successful space missions, this retired NASA medical director takes on chronic lymphocytic leukemia with the help of MD Anderson's Geriatric Clinic.

At age 96, Charles Berry, M.D., has had some out-of-this-world experiences.

A pioneer in the field of aviation medicine, he’s monitored the health of astronauts in space, helped foreign countries develop their own aviation medicine programs, and received more than 50 national and international awards, including two nominations for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

“I’ve had some tremendous opportunities that came at the perfect time,” says Berry, who this summer attended NASA’s 50th anniversary celebration of the historic Apollo 11 moon landing.

Geriatric clinic helps Berry get personalized leukemia treatment

Two years ago, Berry’s zeal for life slowed when he was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, a cancer of the blood and bone marrow. He was referred to MD Anderson’s Geriatric Clinic, where clinic physicians work with MD Anderson cancer specialists to design personalized treatment plans for older adults with cancer.

“Although age is the reason most patients are referred to the Geriatric Clinic, age alone is not a good predictor of how someone will do with their cancer treatment,” says Tacara Soones, M.D., who also holds a master’s degree in public health. “I look at the whole person and their treatment goals to really understand how to tailor their cancer treatment to those goals.”

At the clinic, patients complete a geriatric assessment – a series of tests that evaluate physical and mental ability, along with emotional and social well-being. The tests also help pinpoint the patient’s wishes for treatment and their quality of life.

“Our overall goal is to avoid over-treatment or under-treatment,” Soones says.

A clinic social work counselor serves as a resource not only to patients but also to patients’ caregivers, who typically are family members.

“I spend a lot of time talking with caregivers to make sure they have appropriate breaks and respite during their caregiver duties,” says Tiffany Raczy, social work counselor. “I also help them consider whether they’re prepared to take on increased duties in the future, and assist them in identifying other family members or resources that can provide additional support.”

Raczy then follows up to make sure patients and caregivers have everything they need, and that all their questions are answered.

Berry is pleased with the care he’s received.

“Dr. Soones and the clinic staff provide very personalized treatment and make me feel respected,” he says. “They’re very attentive and help me manage everything going on in my life.”

From family practice to astronaut doctor

The son of a butcher from Rogers, Arkansas, Berry experienced repeated bouts of tonsillitis as a child. After frequent visits to the family doctor, he announced at age 7 that he wanted to become a physician.

In September 1941, he enrolled as a pre-med student at the University of California at Berkeley. Just three months later, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor occurred, and American students over age 18 were given a choice – enlist now and the military will let you finish college, or decline and take your chances with the draft. Berry enlisted in the Navy, then remained in California and attended medical school at the University of California – San Francisco. Before his senior year of medical school, the Navy discharged him with no further obligation. Berry received his medical degree in 1947, and entered into private practice.

Soon, the Korean War broke out, and Berry felt it was his duty to enlist. He joined the Air Force, but only three months later was invited to participate in additional training in a new field called aviation medicine. Instead of heading to the North Pacific, he flew to San Antonio as one of 25 members of the first class of the U.S. Air Force School of Aviation Medicine.

After a year of training, the Air Force sent him to Panama, where he spent three years flying air rescue missions and helping Central and South American countries develop their own aviation medicine programs.

Berry retuned to the United States and completed a public health residency – a requirement of his training with the U.S. Air Force School of Aviation Medicine – at Harvard University’s School of Public Health.

In 1956, he returned to San Antonio and became chief of the Department of Flight Medicine at the Air Force school. While there, he conducted experiments on military pilots by sending them to various elevations, all the way up to the edge of the atmosphere, to see how their bodies would respond to altitude.

Two years later, the U.S. government authorized the creation of NASA. The Soviets had launched the first man-made satellite into space the previous year, and the U.S. was ready to enter the space race.

Berry and a handful of other doctors from around the country received military orders to fly to Washington where they would help select test pilots who would ride a military rocket into outer space.

The orders referred to these test pilots as “astronauts.”

“What’s an astronaut?” Berry recalls asking.

Building on technology the military had developed for relaying data back to the ground from passing planes, Berry and his fellow doctors devised ways to test these future astronauts to determine who could best withstand the demands of space travel, and to monitor their vital signs in outer space.

Berry by this time had retired from the Air Force and gone to work for NASA. He played an instrumental role in selecting the country’s seven original astronauts. Throughout his career, he would help send 42 individuals into space and safely bring them home over the course of 30 manned missions, including the Apollo 11 mission during which Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the moon.

“That was a particularly exciting time,” Berry says. “Short of my wedding day, nothing equals the feeling I had monitoring the crew from the control center when they actually landed on the moon.”