The treatment: Improving on success

Related story: A magnificent seven

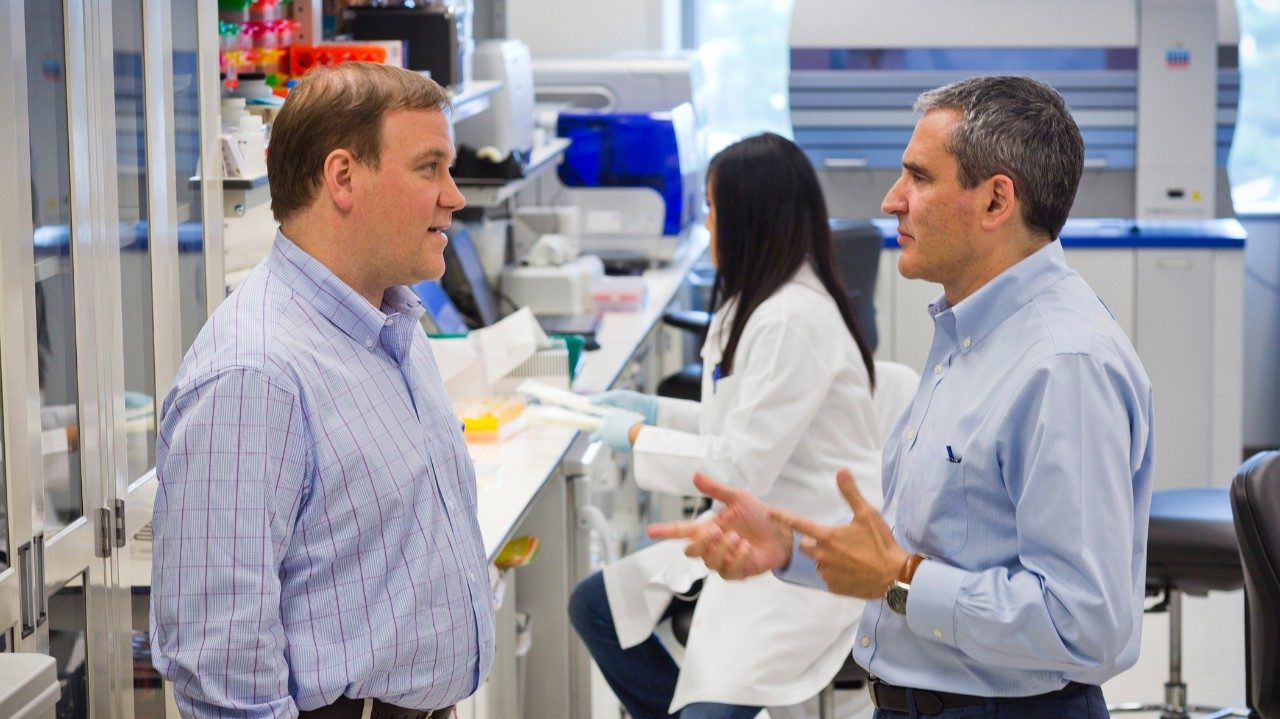

For patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), treatment news has been great since the successful clinical trials for the drug Gleevec® and its approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2001. Now, a new drug — ponatinib, known commercially as Iclusig™ — tackles the previously untreatable T315I mutation of CML and was approved in December 2012 by the FDA. Jorge Cortes, M.D., professor in MD Anderson’s Department of Leukemia, led all of the clinical trials for the drug.

Disease: CML occurs with the overproduction of white blood cells caused by the Philadelphia chromosome, in which swapped DNA creates a mutant fusion bcr-abl protein that drives the disease.

Oral medication: Given at 45 mg per day.

Clinical trial: The pivotal trial showed high rates of major cytogenetic response (reduction of cells expressing the Philadelphia chromosome) and normalization of white blood cell counts.

Patients: Effectiveness and safety were gauged in a clinical trial of 449 patients with varied stages of CML and some with Philadelphia chromosomepositive acute lymphocytic leukemia (PH+ALL).

Results: Of all patients enrolled, 54% achieved major cytogenetic response — as did 70% of those with the T3151 mutation.

“Ponatinib’s availability will drastically improve the outcome of most patients with CML and PH+ALL, who are resistant or intolerant to prior tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy,” Cortes says.

The patient: Back from the brink

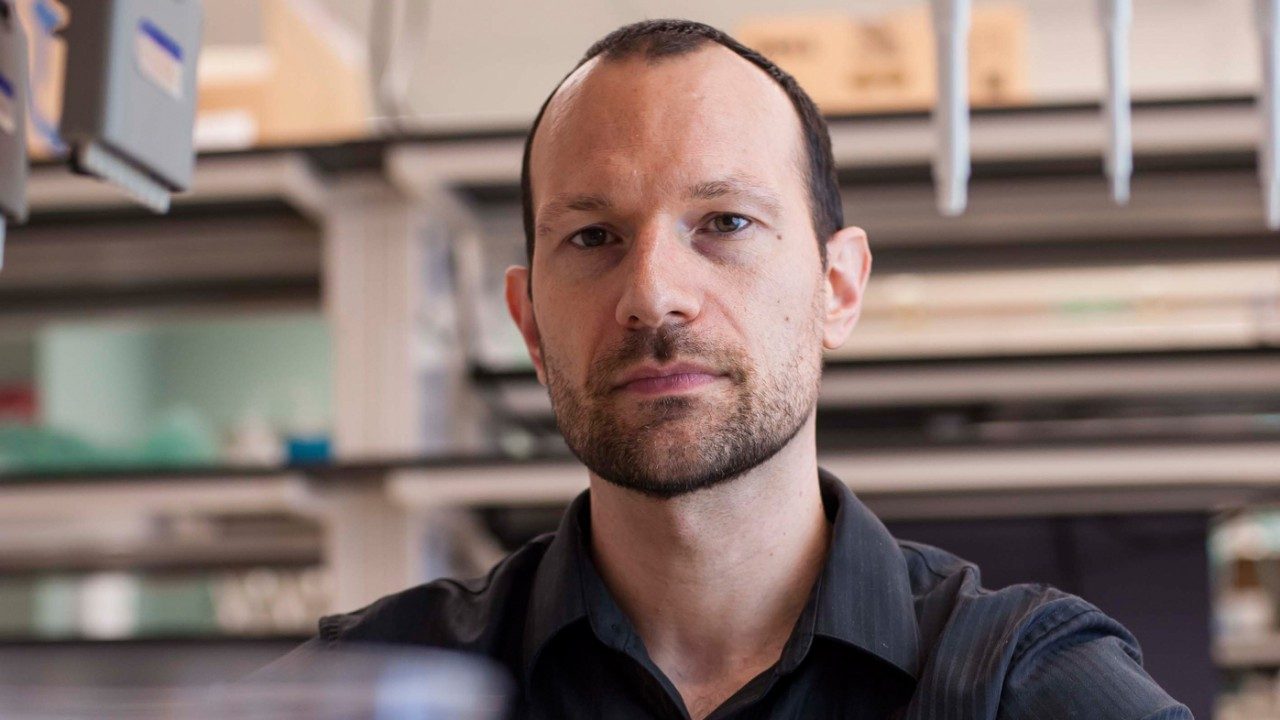

Ever since his diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) at the shockingly young age of 24, Justin Ozuna has benefited from the revolution in disease treatment. But the ride on the new wave of drugs for CML has been more rollercoaster than highway.

At his diagnosis in 2006, Gleevec® had been available five years. Primed to deal with the fusion protein that causes the disease, the drug nearly doubled the percentage of patients who survived for five years, from 50% to 90%.

Ozuna felt good. “But I wasn’t getting quite the response we hoped for. I never went into a deep remission.”

Even so, the drug worked for five years. When it stopped, he shifted to a second-generation drug called dasatinib (Sprycel®). When that drug failed after six months, he ventured from his Dallas-area home to MD Anderson and Jorge Cortes, M.D., professor in the Department of Leukemia.

A new analysis showed that his CML now had the T315I mutation, a variation untreatable by approved drugs. Clinical trials for ponatinib, a promising drug capable of hitting T315I, were closed. Another experimental drug failed, then Cortes secured compassionate use of ponatinib. By October 2012, Ozuna was in complete molecular remission, “about as good as it gets in the CML world.”

Now his life, so frustratingly interrupted for seven years, is in full, focused swing. He works at a utility company, is back in school at The University of Texas at Dallas and will marry his sweetheart, Katie Navarte, in October.

“The best you can hope for with CML, and cancer in general, is to take what works until it doesn’t and hope by then something has come along that works better,” Ozuna says. “And you try to live life in the meantime.”