To treat or not to treat

Active surveillance may be a better choice for some men with prostate cancer

Earl Ritchie had a decision to make. Newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, he needed to select a treatment. One option was aggressive medical interventions that included life-altering side effects. Or he could choose gentler, more conservative therapies that might fall short and allow his cancer to spread.

The stakes were high.

Ritchie’s training as an engineer kicked in as he methodically reviewed each treatment option and created detailed graphs and spreadsheets charting the pros and cons of each.

“Some people get emotional when they hear they have cancer,” he says. “I looked at it as just another problem to solve.”

Ritchie sought advice from doctors who didn’t always agree. He interviewed friends who’d undergone treatment. He scoured countless scientific articles. And when he was finished, he decided to do something radical in modern cancer care: Wait and see.

Instead of treatment, Ritchie opted for active surveillance. It’s an approach offered to men whose prostate cancer is low-risk, meaning it hasn’t spread outside the prostate gland. Doctors perform tests at regular intervals to keep an eye on the cancer. If it advances into the danger zone, they shift from surveillance to active treatment.

“We’re always watching for that red flag,” says Jeri Kim, M.D., Ritchie’s oncologist and a professor of Genitourinary Medical Oncology at MD Anderson. “When and if it happens, we’re ready.”

Blood test, then biopsy

Ritchie first learned he had cancer after taking a prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test that measures a protein that’s produced by the prostate gland and released into the bloodstream. An elevated level suggests possible cancer, but it can also result from a less dangerous enlarged prostate or urinary tract infection. Only about one-fourth of men whose elevated PSA levels lead to further testing actually turn out to have cancer.

“The PSA test is not perfect,” Kim says, “but at this point, it’s the best screening tool we have.”

Because Ritchie’s PSA levels went up, he agreed to a biopsy, a procedure where doctors insert a thin, 12-gauge needle through the rectal wall and into the prostate. The needle returns a dozen or so samples of prostate gland tissue that are about a half of an inch long. By analyzing the tissue under a microscope, doctors can tell whether or not cancer is present.

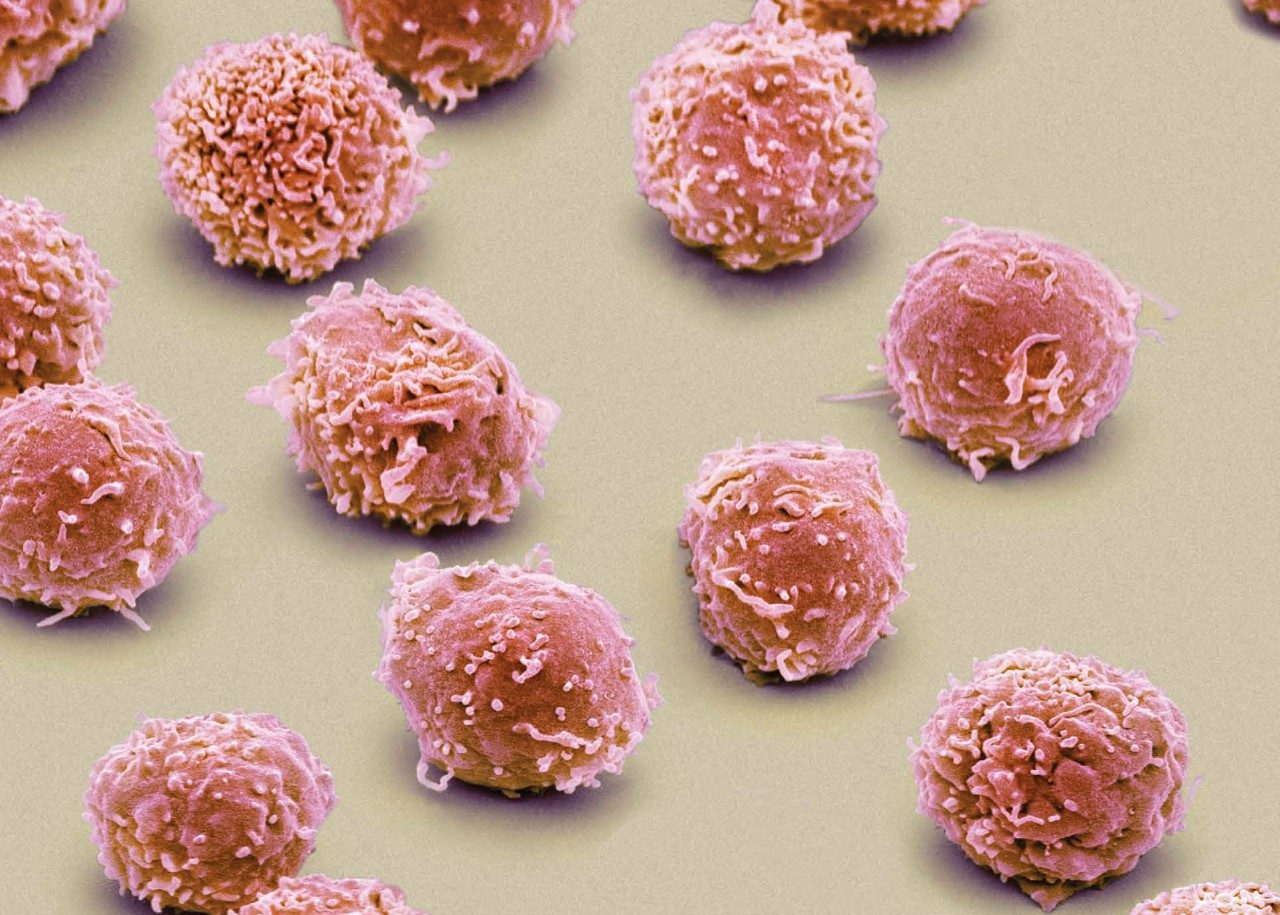

The bad news? The microscope can’t reliably distinguish lethal prostate cancer cells from slow-growing ones that can be safely left alone.

The good news? The vast majority of prostate cancers grow too slowly to ever threaten a man’s life or health.

Tortoises and sloths

Prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer among American men, following skin cancer. Yet it’s so slow-growing that it accounts for only 9% of cancer deaths in the U.S.

According to the American Cancer Society, the 10-year survival rate of all stages of prostate cancer combined is 98%. The 15-year survival rate is 96%.

Kim compares most cases she sees to “tortoises” and “sloths.”

“You’re much more likely to die with, not of, prostate cancer,” she says. “But too many men hear the ‘C’ word and panic. They say, ‘Get it out of me now,’ though their cancer is in fact harmless.”

Most men would live just as long, and be happier, Kim says, if they never found out they had prostate cancer.

Impotence and incontinence

Men who opt for treatment instead of active surveillance undergo surgery to remove the prostate gland or radiation to kill the cancer cells inside. Both treatments can lessen quality of life.

“About half of all men treated will have impotence, urinary incontinence or both,” Kim says. “The treatment may be worse than the disease.”

The walnut-sized prostate gland, which helps produce semen, is lodged deep below the bladder. It surrounds the urethra, through which urine and semen flow, and borders the rectum. The nerves that control erections lie along the prostate like delicate threads. Cut them, and a man becomes impotent. Sometimes drugs like Viagra can help, provided one of the nerves remains intact.

Surgically removing the prostate also removes a valve that controls the flow of urine, which can cause incontinence.

Despite these risks, 60% of the 230,000 men diagnosed with prostate cancer this year in the United States will choose surgery or radiation.

“Because we can’t tell them how aggressive or laid-back their cancer is, they’re afraid,” Kim says. “Fear propels them into immediate treatment.”

Active surveillance, she says, could have preserved their quality of life and prevented unnecessary treatments, or conversely, sounded the alarm if treatment became necessary.

Earl’s story

After seven years under the watchful eyes of MD Anderson doctors, Earl Ritchie’s low-risk cancer was upgraded to high risk.

“The red flag went up,” he says, “and I shifted from active surveillance to treatment.”

Instead of traditional radiation, Ritchie opted for proton therapy, which delivers a high dose of radiation with pinpoint accuracy to attack the specific shape, size and location of the tumor. Because the radiation beam is tightly controlled, less damage occurs in nearby healthy tissues, and side effects are minimized.

Five days a week, for two months, Ritchie began treatment at 4:30 a.m.

In the wee hours of the morning, the waiting room at MD Anderson’s Proton Therapy Center became a makeshift men’s club, where Ritchie bonded with fellow prostate patients.

“We developed a real camaraderie after seeing each other for so long,” he says. “We were all in the same boat, dealing with the same issues.”

Ritchie, who seems to be aging in reverse, returned to college in the midst of treatment and, at age 69, earned a master’s degree in construction management after a 35-year career in the oil and gas industry. At his graduation ceremony, University of Houston President Renu Khator publicly applauded him for being the oldest student in his class.

Today he teaches an introductory course about the oil industry in UH's College of Technology, and contributes to a blog about energy hosted by UH and Forbes.

In hindsight, does Ritchie still believe active surveillance was the right choice?

“Absolutely,” he says. “I had seven wonderful, symptom-free years. Today I have minimal side effects and my prognosis is good.”

Active surveillance

More and more men are gradually warming up to the idea of active surveillance, Kim says. A decade ago, only 10% said OK to the strategy. Today, 40% are embracing it.

“There’s increasing acceptance of this less-invasive approach, which includes regular PSA testing, repeated rectal exams and biopsies to monitor the cancer, rather than aggressive treatment,” she explains.

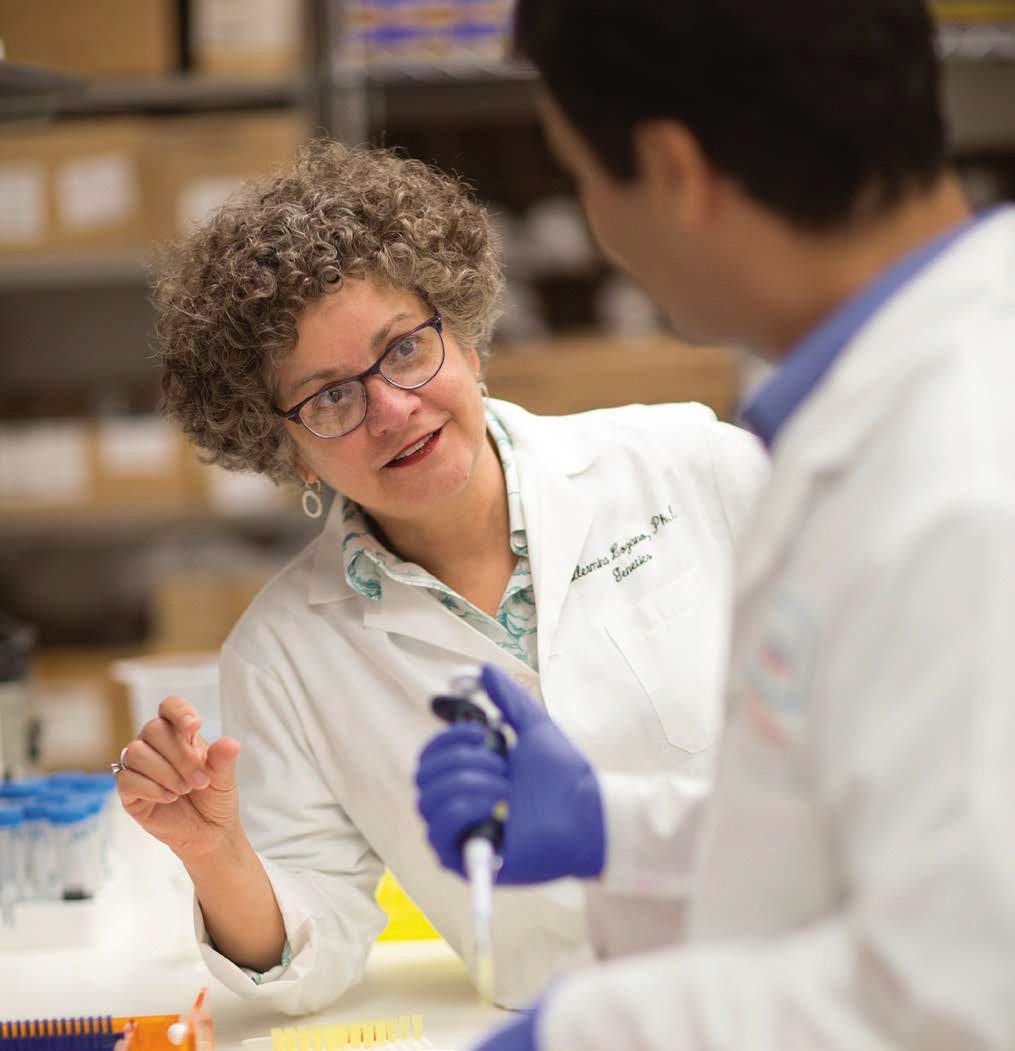

Kim is leading an MD Anderson study to determine active surveillance’s effectiveness in managing prostate cancer. More than 1,100 patients are participating in the clinical trial which launched 11 years ago. None have died from prostate cancer.

Ron Schwartz, 71, is one of the participants. Diagnosed in 2012, his tumor remains low-risk. He monitors his condition with two PSA tests a year and annual biopsies.

“That’s it. No surgery. No radiation,” he says.

He found his way to MD Anderson after a local doctor wanted to surgically remove his prostate.

“I never visited that doctor again,” says Schwartz, who collects, repairs and restores antique fountain pens. An avid proponent of active surveillance, he leads an MD Anderson support group for men with prostate cancer.

“I tell them to slow down and not do anything drastic,” Schwartz says. “MD Anderson is looking out for them. They can stop worrying and relax.”

Should you be screened for prostate cancer?

This past spring, the United States Preventive Services Task Force, a panel of independent experts on prevention and evidence-based medicine that advises the federal government, updated its position on prostate cancer screening.

The panel’s draft recommendation states that “men between the ages of 55 and 69 should discuss the PSA test’s potential benefits and harms with their doctors and make decisions based on their own values and preferences.”

This is a turnaround of the panel’s 2012 position, which advised against routine PSA screening for all men, regardless of age. The panel’s latest recommendation leaves in place its 2012 suggestion that men age 70 and older forgo screening altogether.

The latest proposed guidelines are based on several studies that have reinforced not only the benefits of PSA tests but also ways to lessen the harms of screening, which include unnecessary biopsies and treatments.

One of the studies that influenced the committee’s decision was published last October in the New England Journal of Medicine. The study demonstrated that doctors could safely monitor a patient’s prostate cancer – largely through repeated PSA checks – without rushing to treat it.

In the study, only about 1% of men died of prostate cancer over 10 years, with no significant differences between those who were treated and those who were followed with active surveillance.

Five years ago when the 2012 recommendation not to screen was issued, screening rates dropped dramatically.

“Our hope is that with this new recommendation, patients will be diagnosed when their disease is still low-risk,” MD Anderson oncologist Jeri Kim, M.D., said.

“Prostate cancer causes no symptoms until it’s advanced, so screening is very important to find life-threatening cancers in time for a cure.”

Kim also hopes the panel will issue more specific guidelines for high-risk patients, including African-Americans and those with a family history of the disease.

Other medical groups have mixed recommendations. The American Urological Association recommends shared decision-making between physicians and patients aged 55 to 69, while the American Academy of Family Physicians advises against routine prostate cancer screening. The American Cancer Society recommends starting the conversation between doctor and patient at age 50, and even younger if patients are high risk.

The latest prostate cancer screening recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force are still in draft form, while panel members review public feedback. The final recommendation will be published at a yet-to-be-determined date.