Prostate cancer survivor thankful for second opinion at MD Anderson

Bill Kish’s prostate cancer diagnosis came after his doctor felt something unusual during his annual physical. Blood work showed his PSA level was at 5.3. He was 69, so this was higher than the normal range for a man his age.

A local urologist in San Antonio performed a CT scan and prostate biopsy to confirm that Bill had cancer. But he and his wife, Jacki, weren’t comfortable with the doctor’s diagnosis.

What is a vulvectomy? Purpose, procedure and recovery

Prostate cancer survivor thankful for second opinion at MD Anderson

Manual lymph drainage: What to know about exercises for lymphedema relief

Neoplasms 101: What they are and how they’re treated

10 cancer symptoms women shouldn't ignore

What is a Living Will?

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

|---|

|

Healthy Living

|

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

|

Research

|

|

Healthy Living

|

Find stories by topic

Find out everything you need to know to navigate a cancer diagnosis and treatment from MD Anderson’s experts.

What is a vulvectomy? Purpose, procedure and recovery

June 12, 2025

Neoplasms 101: What they are and how they’re treated

June 10, 2025

10 cancer symptoms women shouldn't ignore

June 09, 2025

What is a Living Will?

June 06, 2025

Acupuncture during cancer treatment: What to know

June 05, 2025

What causes chemobrain? New insights

June 03, 2025

When should you worry about your menstrual cycle?

June 02, 2025

Read inspiring stories from patients and caregivers – and get their advice to help you or a loved one through cancer.

Mom's legacy lives on through fundraising for MD Anderson

April 28, 2025

Get MD Anderson experts’ advice to help you stay healthy and reduce your risk of diseases like cancer.

What SPF should I use?

May 23, 2025

Is raw milk safe?

May 16, 2025

How much caffeine is too much?

May 09, 2025

Learn how MD Anderson researchers are advancing our understanding and treatment of cancer – and get to know the scientists behind this research.

What causes chemobrain? New insights

June 03, 2025

Nutrivention: Food as medicine

May 28, 2025

5 emerging therapies presented at ASCO 2025

May 28, 2025

Top 5 MD Anderson abstracts at AACR 2025

April 25, 2025

Cell therapy: The evolution of the ‘living drug’

April 22, 2025

How non-scientists are helping cancer researchers

February 21, 2025

4 questions with immunology researcher Susan Bullman

February 04, 2025

4 questions for mathematical oncologist Heiko Enderling, Ph.D.

January 28, 2025

Read insights on the latest news and trending topics from MD Anderson experts, and see what drives us to end cancer.

What is a Living Will?

June 06, 2025

Surgeon-scientist: ‘MD Anderson is unique’

May 15, 2025

Find out what inspires our donors to give to MD Anderson, and learn how their generous support advances our mission to end cancer.

Mom's legacy lives on through fundraising for MD Anderson

April 28, 2025

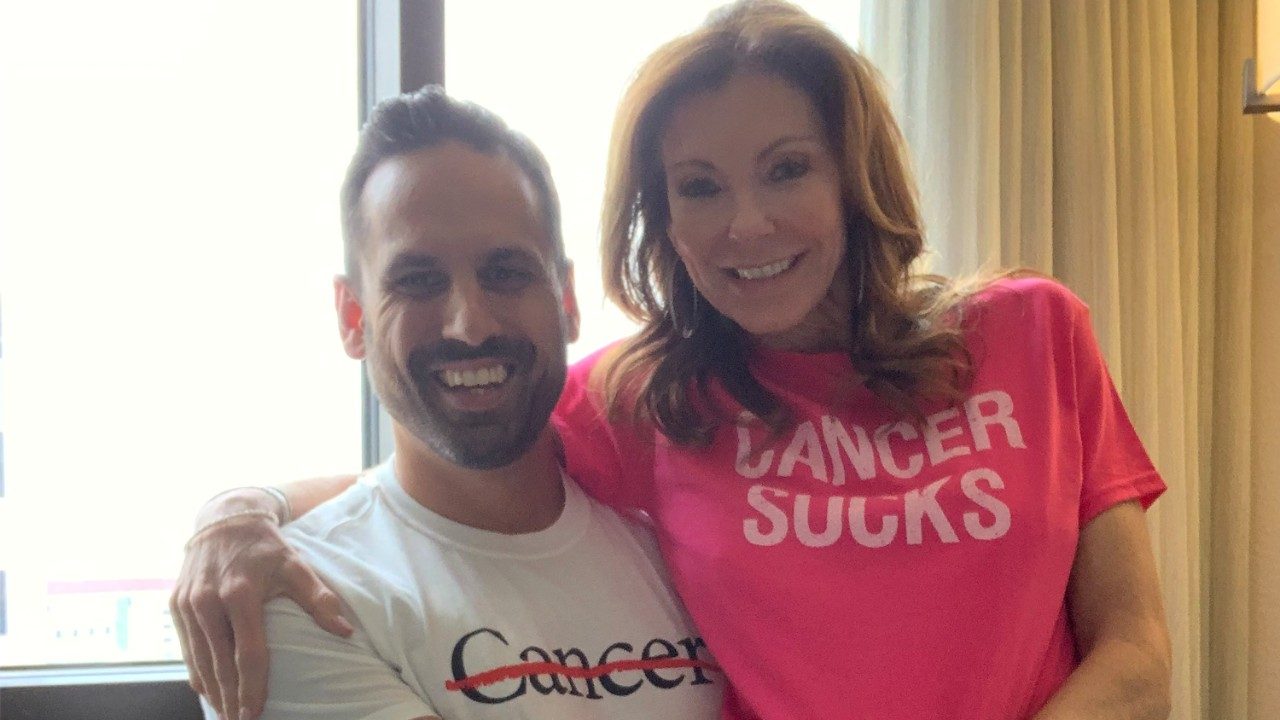

Three cancer survivors raise funds to support Colorado patients

October 03, 2024

Inflammatory breast cancer survivor finds hope at MD Anderson

October 24, 2023