Hands-on environment to test surgical skills

Nicholas Levine, M.D., calls the Microsurgical and Endoscopic Center for Clinical Applications his field of dreams.

Hands-on cadaver training had, after all, been critical to his own development as an expert in skull-base surgery. He envisioned a dedicated space where

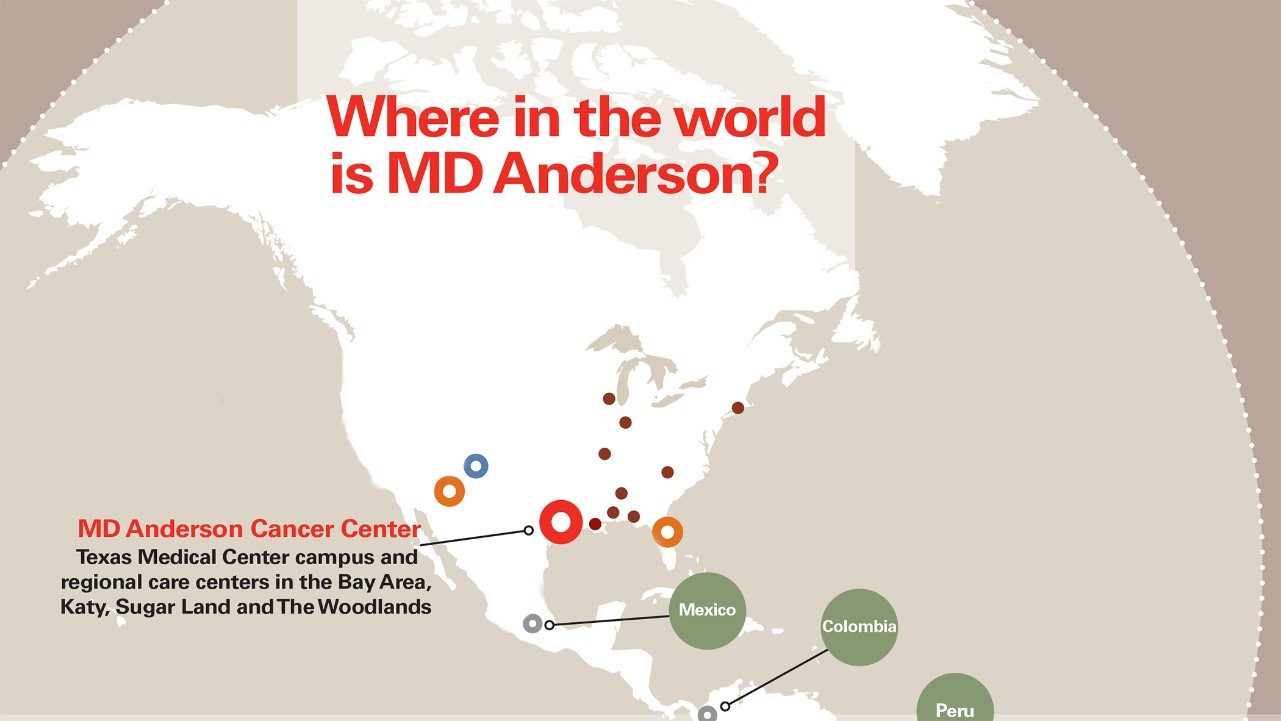

MD Anderson’s residents and fellows could hone their surgical skills on anatomic specimens and rehearse complex, multidisciplinary cases without venturing far from campus.

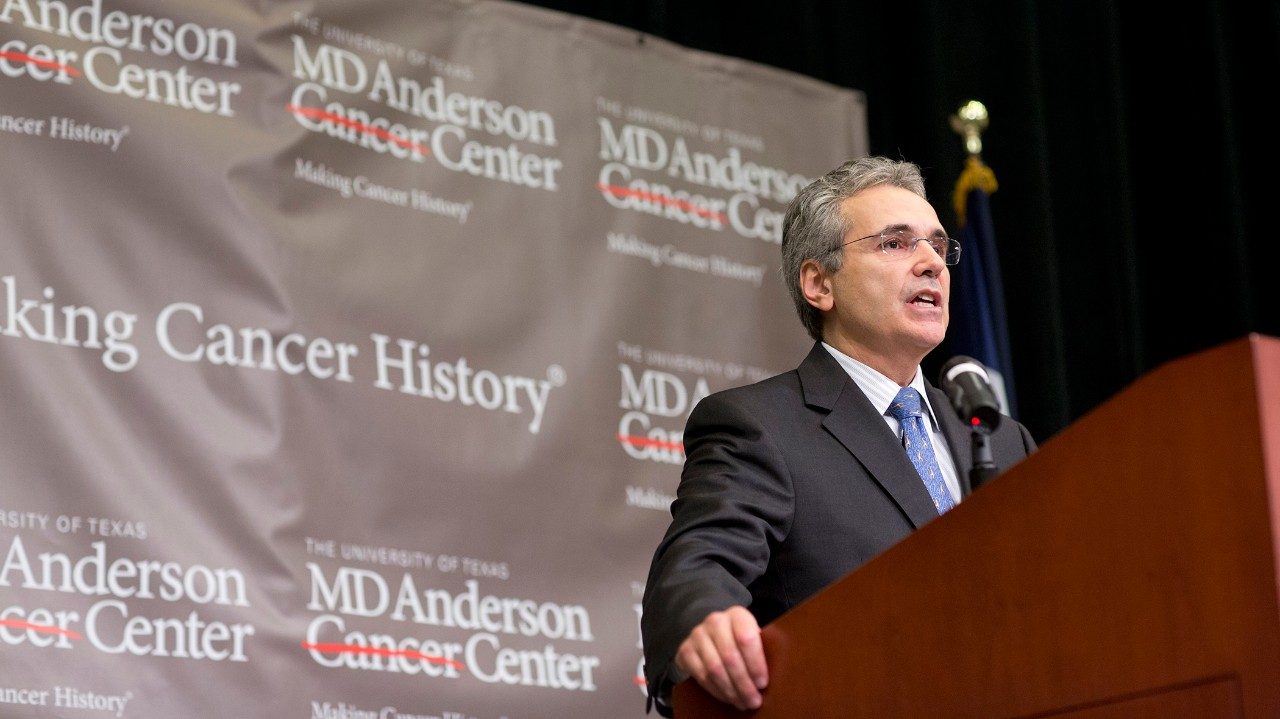

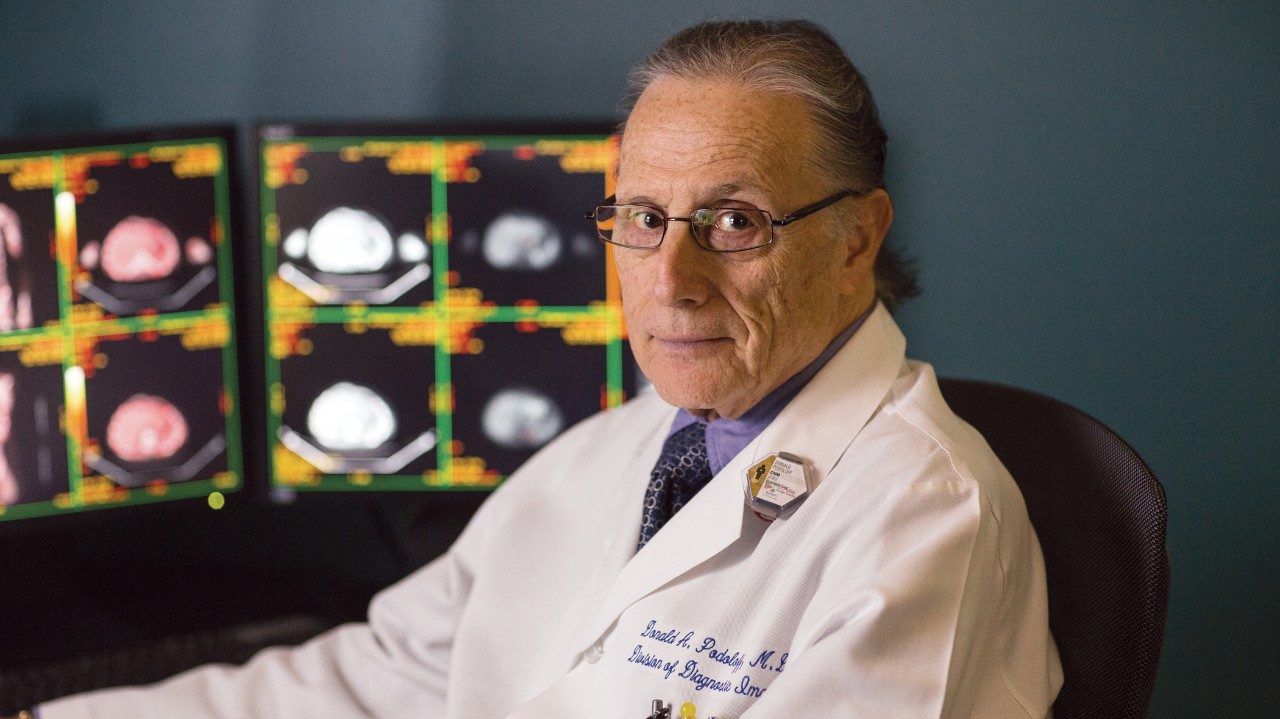

Raymond Sawaya, M.D., encouraged Levine to think big. As professor and chair of neurosurgery at MD Anderson and Baylor College of Medicine, Sawaya helped secure space for the visionary laboratory at Baylor, which offers access to its cadaver program.

Levine tapped his ingenuity and donor relationships to fill the space with 11 modular workstations that could be configured for various disciplines of neurosurgery.

He won the support of colleagues like Franco DeMonte, M.D., professor in the Department of Neurosurgery, who contributed funding from the Mary Beth Pawelek Chair in Neurosurgery for MD Anderson; and he negotiated discounts with surgical equipment providers to outfit the space in the style of today’s advanced operating rooms.

“We ended up having a state-of-the-art facility akin to private surgery centers,” Levine says, reasonably surprised he didn’t face greater obstacles in its development. “The center’s truly grander than I imagined it would be. I set out raising the money after I came up with the idea. I didn’t give myself a budget and say this is what I want to accomplish.”

The laboratory welcomed its first neurosurgical trainees in January 2012, and other surgical disciplines have followed, hosting courses in plastic surgery, head and neck dissection and thoracic study.

Sawaya commends Levine’s efforts to bring the high-tech learning space into fruition: “It’s masterful, I would say.”

Surgical training goes modular

The David C. Nicholson Microsurgical and Endoscopic Center for Clinical Applications brings cadaveric learning into the 21st century.

Modular workstations — Each of its 11 stations (soon to expand to 17) can be configured to support almost any surgical specialty or approach. Stations can be moved, modeled and removed from the 1,500-square-foot space to support the educational goal.

Integrated technology — Students never have to leave their workstations to gather around a proctor station. Each work station is equipped with overhead cameras attached to LED surgical lights, enabling one workstation to broadcast to the entire room and outside audiences via captured recordings. The same holds true for robotic and endoscopic observations.

Conferencing support — Adjacent conference rooms provide opportunities for follow-up discussions and distance learning.

“The foundation for surgical education is anatomy,” says Nicholas Levine, M.D., assistant professor in MD Anderson’s Department of Neurosurgery. “The beauty of having one space that’s modular is that you bring everyone together instead of having them use separate spaces with no cross-fertilization between activities.”