Program addresses body image concerns

Patient adjusts to 'new normal'

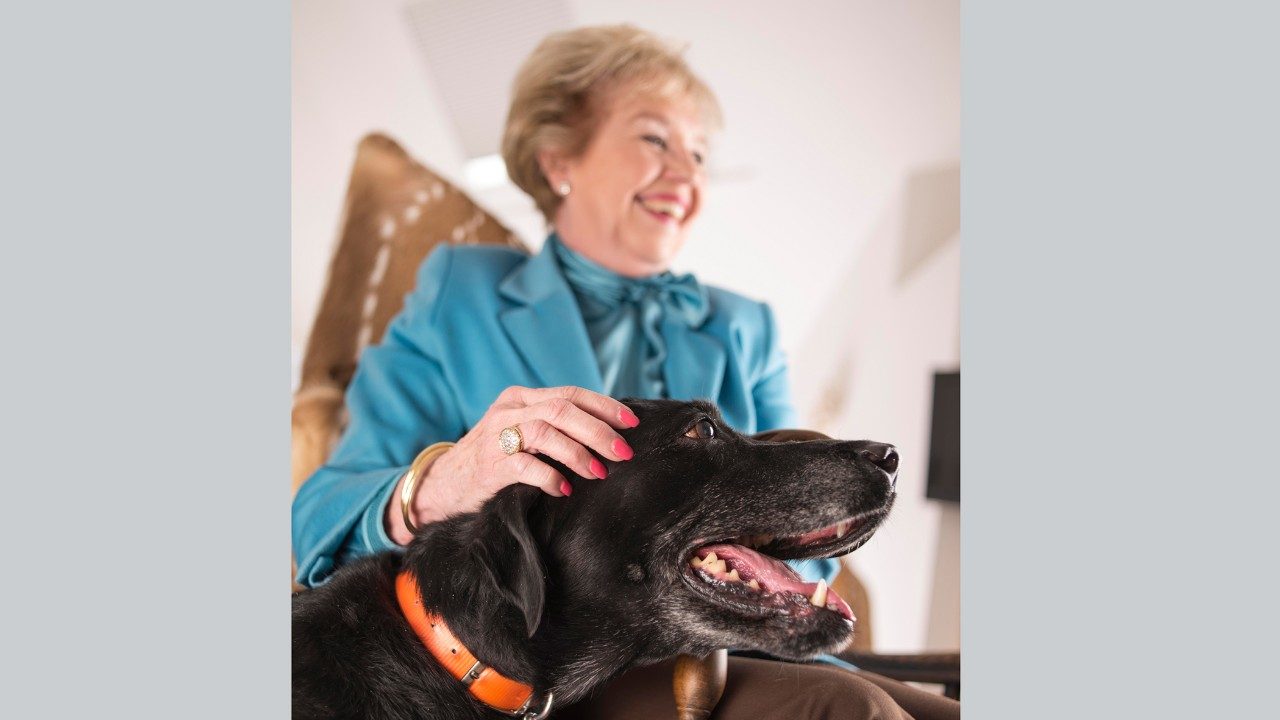

Debbie Cally doesn’t mind when children ask about her missing left eye. “I just say, ‘I had a big bo-bo, but the doctors took it out. I feel really good now.’”Cally came to MD Anderson in 2010 for treatment of osteosarcoma of the maxilla, the upper jaw bone. She’s adjusted to her “new normal” thanks to a health care team that includes Michelle Fingeret, Ph.D., director of the Body Image Therapy Program.“I’ve done so well due in large part to Michelle,” she says.Today, Cally stays busy caring for her mother. She also is learning to knit, crochet and scrapbook.“If I hadn’t had surgery, the cancer probably would have spread to my brain. What’s the loss of your eye compared to your life?”

DID YOU KNOW?

From 2008 to 2012, the Body Image Therapy Program:

- provided therapy services to 623 patients,

- received four extramural grants from agencies like the National Institutes of Health and American Cancer Society,

- received three internal grants from MD Anderson and

- had more than 900 patients enrolled in various research studies.

Helping patients deal with body-image concerns

You can’t always see cancer’s side effects. Yet, changes in appearance or bodily functions sometimes lead to depression, anxiety and withdrawal.

MD Anderson’s Body Image Therapy Program, directed by Michelle Fingeret, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Behavioral Science, is here to help.

From its beginnings in 2008 with a staff of just Fingeret and a part-time research assistant, the program has grown to include a psychologist, two psychology fellows and five full-time researchers.

The program consists of research and clinical components, and its staff works closely with multidisciplinary health care teams.

“We even have biomedical engineers because we look at body image from multiple perspectives, which include using three-dimensional modeling and visualization technologies,” Fingeret explains.

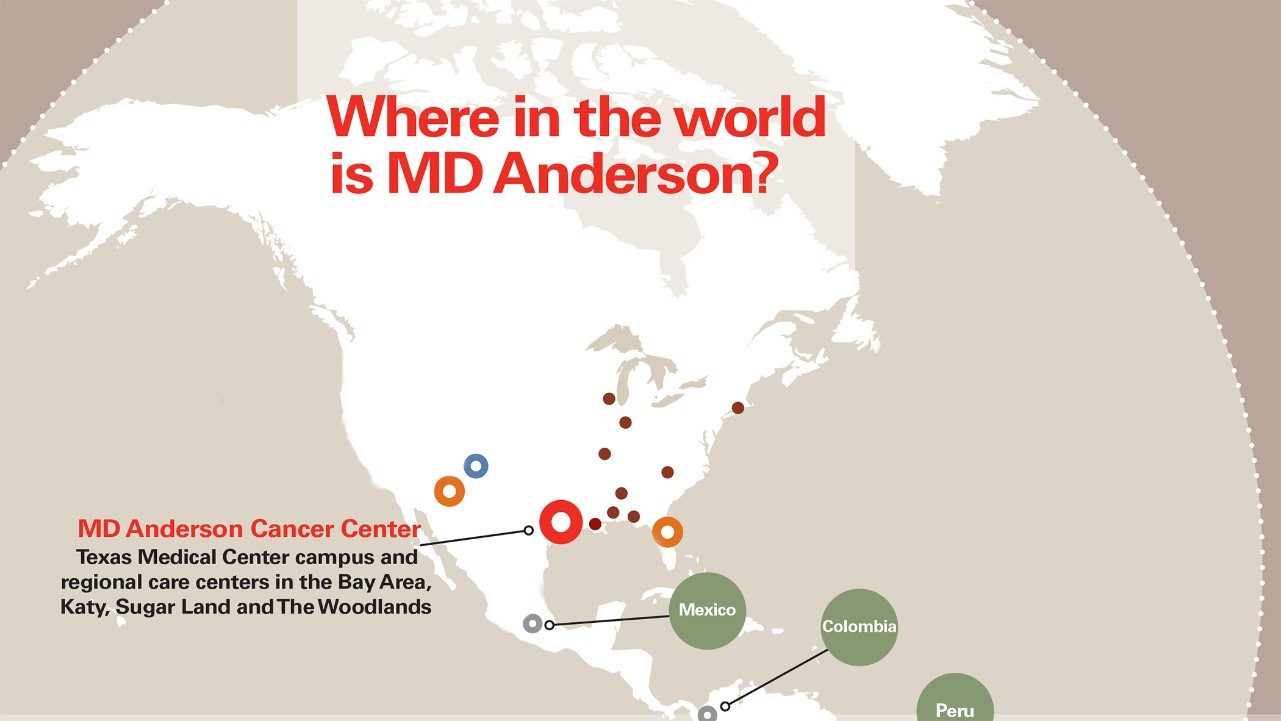

Most patients seen by Fingeret’s team have either head and neck cancer or breast cancer, since those two groups are known to experience considerable difficulties adjusting to body-image changes that result from cancer and its treatment. They can be referred to the program by any member of their health care team. Or they can refer themselves.

“That’s very important,” Fingeret says. “Some patients don’t feel comfortable talking to their physicians about body-image concerns. We want to do all we can to reduce barriers to patients accessing our services.”

Understanding body-image issues

Passionate interest leads to groundbreaking program

Michelle Fingeret, Ph.D., thought something was lacking at MD Anderson. So she decided to fix the unmet need.

She had been keenly interested in the field of body image since her graduate school days in the late 1990s. Back then, researchers primarily studied body image as it related to people with eating disorders, like anorexia and bulimia.

Fingeret sought out a postdoctoral fellowship at MD Anderson because she knew another group of people often had these issues: cancer patients. She understood much more could be done to help them deal with body-image concerns.

“We had counseling services here, but we didn’t address coping with disfigurement and other bodily changes that can occur after treatment,” recalls Fingeret, assistant professor in MD Anderson’s Department of Behavioral Science and director of the program. “So I went to the chairs of the departments of Plastic Surgery [Geoffrey Robb, M.D.] and Head and Neck Surgery [Randal Weber, M.D.], and told them ‘I think your patients could use help with body image.’”

Those initial conversations led to the development of MD Anderson’s Body Image Therapy Program. Some five years later, Fingeret still works closely with Robb and Weber. “They’ve always been active partners and champions of our services,” she says.

Fingeret remains fascinated by her chosen field. “This is fulfilling and energizing work,” she says. “Our patients are very inspiring.”