- Diseases

- Acoustic Neuroma (14)

- Adrenal Gland Tumor (24)

- Anal Cancer (68)

- Anemia (2)

- Appendix Cancer (16)

- Bile Duct Cancer (26)

- Bladder Cancer (72)

- Brain Metastases (28)

- Brain Tumor (232)

- Breast Cancer (714)

- Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (2)

- Cancer of Unknown Primary (4)

- Carcinoid Tumor (8)

- Cervical Cancer (158)

- Colon Cancer (166)

- Colorectal Cancer (118)

- Endocrine Tumor (4)

- Esophageal Cancer (44)

- Eye Cancer (36)

- Fallopian Tube Cancer (8)

- Germ Cell Tumor (4)

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (2)

- Head and Neck Cancer (12)

- Kidney Cancer (128)

- Leukemia (342)

- Liver Cancer (50)

- Lung Cancer (286)

- Lymphoma (278)

- Mesothelioma (14)

- Metastasis (30)

- Multiple Myeloma (100)

- Myelodysplastic Syndrome (60)

- Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (6)

- Neuroendocrine Tumors (16)

- Oral Cancer (100)

- Ovarian Cancer (172)

- Pancreatic Cancer (160)

- Parathyroid Disease (2)

- Penile Cancer (14)

- Pituitary Tumor (6)

- Prostate Cancer (146)

- Rectal Cancer (58)

- Renal Medullary Carcinoma (6)

- Salivary Gland Cancer (14)

- Sarcoma (238)

- Skin Cancer (296)

- Skull Base Tumors (56)

- Spinal Tumor (12)

- Stomach Cancer (64)

- Testicular Cancer (28)

- Throat Cancer (92)

- Thymoma (6)

- Thyroid Cancer (98)

- Tonsil Cancer (30)

- Uterine Cancer (80)

- Vaginal Cancer (16)

- Vulvar Cancer (20)

- Cancer Topic

- Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Issues (20)

- Advance Care Planning (10)

- Biostatistics (2)

- Blood Donation (18)

- Bone Health (8)

- COVID-19 (362)

- Cancer Recurrence (120)

- Childhood Cancer Issues (120)

- Clinical Trials (632)

- Complementary Integrative Medicine (22)

- Cytogenetics (2)

- DNA Methylation (4)

- Diagnosis (232)

- Epigenetics (6)

- Fertility (62)

- Follow-up Guidelines (2)

- Health Disparities (14)

- Hereditary Cancer Syndromes (126)

- Immunology (18)

- Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (8)

- Mental Health (116)

- Molecular Diagnostics (8)

- Pain Management (62)

- Palliative Care (8)

- Pathology (10)

- Physical Therapy (18)

- Pregnancy (18)

- Prevention (918)

- Research (392)

- Second Opinion (74)

- Sexuality (16)

- Side Effects (604)

- Sleep Disorders (10)

- Stem Cell Transplantation Cellular Therapy (216)

- Support (402)

- Survivorship (322)

- Symptoms (182)

- Treatment (1786)

Gastrointestinal medical oncologist and researcher driven to help patients live longer

4 minute read | Published October 08, 2024

Medically Reviewed | Last reviewed by Van Morris, M.D., on October 08, 2024

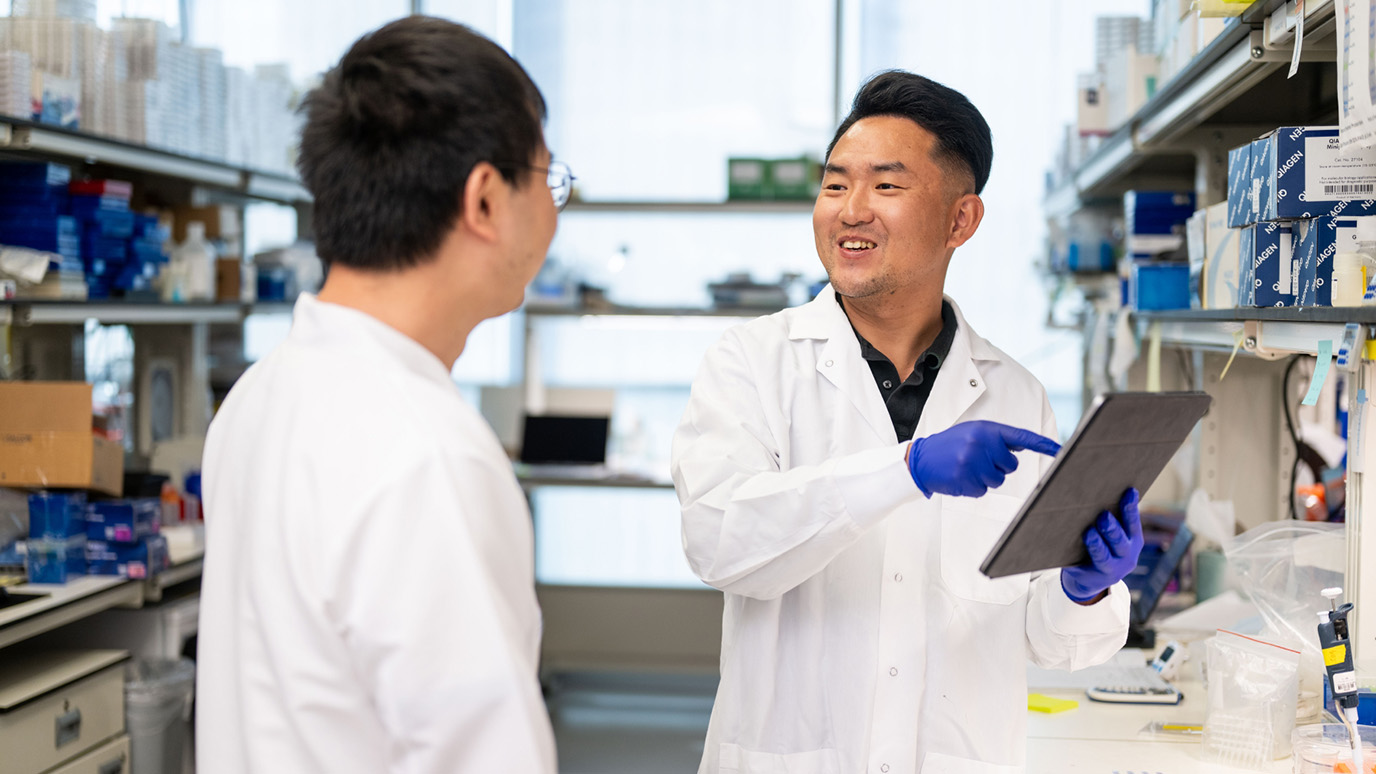

Van Morris, M.D., is driven to offer more to patients.

“I am reminded every day about the opportunities for improving treatments for our patients with cancers in the GI tract,” says Morris, a gastrointestinal medical oncologist and clinician scientist. “This fuels my passion to use research to do more to help our patients and their families, and to help patients everywhere live longer.”

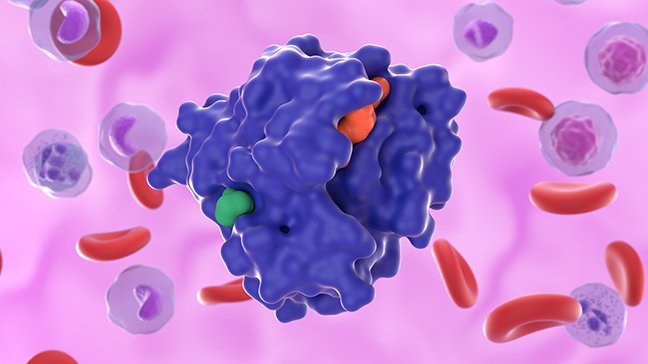

Throughout his career, Morris has led clinical trials that have led to insights into the treatment and defining factors of colorectal cancer. In 2022, he received a grant from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) to examine the cancer cells that remain after treatment and contain a protein called TGF-beta. This protein plays a crucial role in controlling the cell’s responses during growth and other critical functions.

Fellowship fuels discoveries

That same year he was named to the class of Sabin Family Fellows. Made possible by a generous endowment from philanthropist Andrew Sabin, the fellowship provides up-and-coming faculty members with $100,000 to pursue potentially practice-changing science early in their careers when federal and private funding opportunities are often limited.

The Sabin fellowship has empowered Morris to study MSS BRAF V600E, a mutation in the BRAF gene that can be found in microsatellite sable (MSSS0) colorectal cancers. Patients with this type of mutation have relatively stable DNA. For the most part, the error-checking process in their DNA works correctly. But they have a mutation found in the BRAF protein that causes it to constantly activate and reproduce, leading to a tumor. This relatively rare type of cancer accounts for 5% of colorectal cancer cases and is difficult to treat.

Tackling even the rarest of deadly cancers

In 2015, Morris’ mentor, Scott Kopetz, M.D., Ph.D., conducted a study that established the standard of care for people with MSS BRAFV600E: two drugs, encorafenib and cetuximab. Encorafenib targets and stops the mutated BRAF protein from growing, and certuximab, blocks the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), further preventing growth. It helped patients live longer, but the median survival was still only four months. Morris wanted to continue this legacy of work on the Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology team.

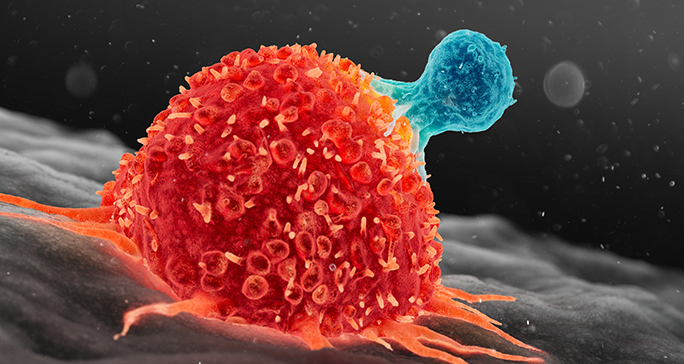

He continued to learn more about the mutation and saw that it was characterized by a high immune system response. He wondered if immunotherapy could be used to treat this cancer successfully.

Morris investigated taking this regimen and adding a type of immunotherapy, anti-PD1 therapy. Cancer cells can trick the immune system into not working, but anti-PD1 therapy prevents this, allowing the immune system to attack the cancer. Some cancer cells can evade the immune system, thanks to a protein called PD-L1. It sends off signals to T cells. While T cells are designed to wipe out infected or cancerous cells, those signals trick them into leaving the cancer cells alone so they can spread. For that to occur, PD-L1 has to first bind with another protein, PD1. So anti-PD1 therapy stops that interaction from taking place and makes it impossible for PD-L1 to send the off signals. This allows the T cell to recognize and attack the cancer cells.

The median survival extended to almost 7-and-a-half months. Two patients classified as “exceptional responders” stayed on the treatment for two years.

The clinical trial was conducted during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic when it was difficult to enroll patients. But the results were promising.

“These were amazing results we were not used to seeing in enough of our patients with BRAF-mutated colorectal cancer,” Morris says.

Based on these findings, Morris is now leading a nationwide clinical trial as lead investigator testing this combination across sites across the United States.

Learning what allows some people to have exceptional responses

Morris began to collect more information about patients with the BRAF gene mutation. He worked with researcher Anirban Maitra, M.B.B.S., to conduct liquid biopsies and collect blood samples from patients in the study. Researchers then examined RNA signatures from these liquid biopsies. They found that the exceptional responders’ RNA had differences from that of other patients. While the trial had been small, it gave credibility to the idea that conducting a larger trial and examining even more patients’ RNA could shed greater light into what makes treatment successful for a patient with a rare mutation.

Now, Morris is the principal investigator of a randomized Phase II clinical trial evaluating this combination of treatments and analyzing liquid biopsies.

“The ability to conduct high-impact clinical research with first-in-kind clinical trials is unparalleled at MD Anderson,” he says. “This offers our patients the highest quality of patient care beyond standard practices.”

Learn about research careers at MD Anderson.

I am reminded every day about the opportunities for improving treatments for our patients with cancers in the GI tract.

Van Morris, M.D.

Physician & Researcher