- Diseases

- Acoustic Neuroma (14)

- Adrenal Gland Tumor (24)

- Anal Cancer (68)

- Anemia (2)

- Appendix Cancer (16)

- Bile Duct Cancer (26)

- Bladder Cancer (72)

- Brain Metastases (28)

- Brain Tumor (232)

- Breast Cancer (714)

- Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (2)

- Cancer of Unknown Primary (4)

- Carcinoid Tumor (8)

- Cervical Cancer (158)

- Colon Cancer (166)

- Colorectal Cancer (116)

- Endocrine Tumor (4)

- Esophageal Cancer (44)

- Eye Cancer (36)

- Fallopian Tube Cancer (8)

- Germ Cell Tumor (4)

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (2)

- Head and Neck Cancer (12)

- Kidney Cancer (128)

- Leukemia (342)

- Liver Cancer (50)

- Lung Cancer (286)

- Lymphoma (278)

- Mesothelioma (14)

- Metastasis (30)

- Multiple Myeloma (100)

- Myelodysplastic Syndrome (60)

- Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (4)

- Neuroendocrine Tumors (16)

- Oral Cancer (100)

- Ovarian Cancer (172)

- Pancreatic Cancer (160)

- Parathyroid Disease (2)

- Penile Cancer (14)

- Pituitary Tumor (6)

- Prostate Cancer (146)

- Rectal Cancer (58)

- Renal Medullary Carcinoma (6)

- Salivary Gland Cancer (14)

- Sarcoma (238)

- Skin Cancer (296)

- Skull Base Tumors (56)

- Spinal Tumor (12)

- Stomach Cancer (64)

- Testicular Cancer (28)

- Throat Cancer (92)

- Thymoma (6)

- Thyroid Cancer (96)

- Tonsil Cancer (30)

- Uterine Cancer (80)

- Vaginal Cancer (16)

- Vulvar Cancer (20)

- Cancer Topic

- Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Issues (20)

- Advance Care Planning (10)

- Biostatistics (2)

- Blood Donation (18)

- Bone Health (8)

- COVID-19 (362)

- Cancer Recurrence (120)

- Childhood Cancer Issues (120)

- Clinical Trials (630)

- Complementary Integrative Medicine (22)

- Cytogenetics (2)

- DNA Methylation (4)

- Diagnosis (232)

- Epigenetics (6)

- Fertility (62)

- Follow-up Guidelines (2)

- Health Disparities (14)

- Hereditary Cancer Syndromes (126)

- Immunology (18)

- Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (8)

- Mental Health (116)

- Molecular Diagnostics (8)

- Pain Management (62)

- Palliative Care (8)

- Pathology (10)

- Physical Therapy (18)

- Pregnancy (18)

- Prevention (914)

- Research (392)

- Second Opinion (74)

- Sexuality (16)

- Side Effects (604)

- Sleep Disorders (10)

- Stem Cell Transplantation Cellular Therapy (216)

- Support (402)

- Survivorship (320)

- Symptoms (182)

- Treatment (1786)

Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT): Diagnosis, treatment and outlook

3 minute read | Published December 27, 2023

Medically Reviewed | Last reviewed by an MD Anderson Cancer Center medical professional on December 27, 2023

Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) is a fast-growing cancerous tumor that develops in the central nervous system, located in the brain and/or spinal cord.

ATRT is an embryonal tumor. This is a brain tumor that develops from an uncontrolled growth of cells left over from fetal development. ATRT is extremely rare. It typically occurs in very young children.

To learn more, we spoke with radiation oncologist Susan McGovern, M.D., Ph.D., who specializes in treating children and adults with brain and spine tumors. Here, she answers our questions about ATRT.

What are the symptoms of ATRTs?

These tumors can occur anywhere in the brain. The most common symptoms are headaches, nausea and vomiting.

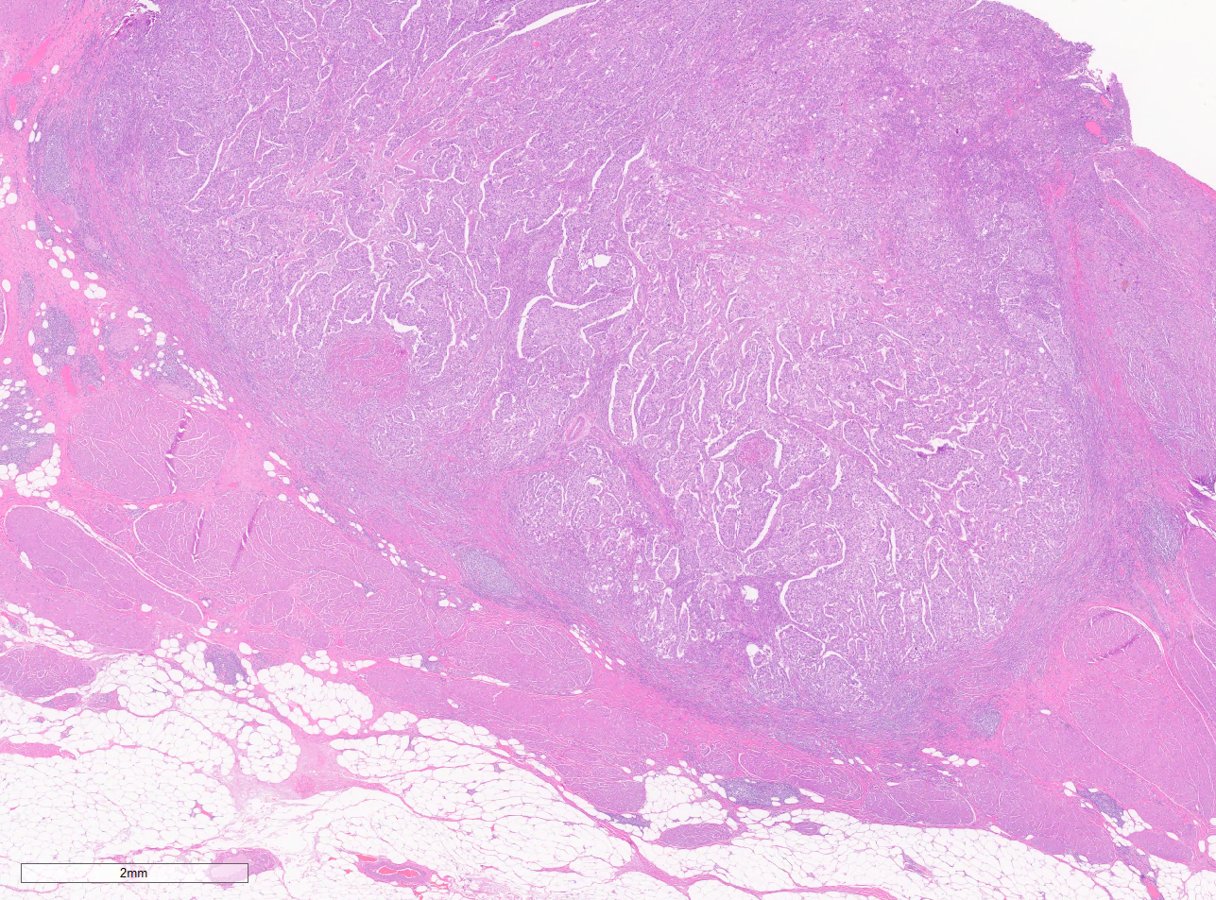

How are ATRTs diagnosed?

ATRTs can be found in older children and rarely in adults, but most diagnoses occur in children ages 1 to 3. Because these tumors are so rare and their symptoms can mimic other childhood medical conditions, getting an ATRT diagnosis can be difficult.

“There needs to be a clinical picture for a brain tumor,” says McGovern. “It wouldn’t be, ‘My child threw up yesterday, and now they’re fine.’ It would be, ‘My child has been throwing up for a week and has a bad headache.’”

A pediatrician or other doctor may start with a CT scan of the head. If they identify something, such as a brain mass, then the patient would get an MRI.

“Once a mass is identified, depending on the clinical situation, the patient will have the tumor resected,” says McGovern. “The tumor will be analyzed by a pathologist, and that’s when the official diagnosis of ATRT can be made.”

How are ATRTs treated?

Treatment for ATRT depends on several factors, such as the patient’s age and the tumor’s size and location. Most patients need multimodality therapy, which often includes surgery and chemotherapy.

During surgery, the surgeon removes as much of the tumor as possible and obtains tissue for a diagnosis. Chemotherapy is used to shrink the tumors and kill the remaining cancer cells. Some patients may also receive radiation therapy.

“The extent of radiation will depend on whether or not the tumor has spread,” says McGovern. “If the tumor is localized, we’ll do local radiation to the tumor only. If the cancer has spread, depending on the patient’s age and response to chemotherapy, we may do craniospinal radiation, which is radiation to the whole brain and spine.”

Typically, doctors try to avoid radiation in very young children.

“Age 0 to 3 is a critical period for a child’s brain and spinal cord development, and radiation can adversely impact that development,” she explains. “Especially in children younger than 3, we try to minimize radiation by using chemotherapy to delay or reduce radiation.”

What is the outlook for patients with ATRT?

ATRT’s curability and survival rates depend on several factors, so it’s important to talk to your doctor about your prognosis.

When discussing survival rates, McGovern points to results from a recent clinical trial, which found that patients with ATRT treated with surgery followed by high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell rescue and focal radiation had overall survival rates of 43% and event-free survival rates of 37%. These are improved rates compared to data from past studies. About 83% of evaluated patients were younger than 3 years old.

“I encourage all patients with ATRT to enroll in clinical trials where they’re available,” says McGovern. “Aggressive multimodality therapy is improving outcomes in this aggressive disease, but there is much room for improvement.”

What else should we know about ATRT?

Multidisciplinary care is important for very young patients with ATRT.

“Having a dedicated team with a pediatric neurosurgeon, pediatric neurooncologist and pediatric radiation oncologist working together to map out the most appropriate treatment leads to the best outcomes for these patients,” says McGovern.

As for the future of ATRT treatment, McGovern would like to see a better understanding of the molecular and genetic drivers of ATRTs.

“That’s going to give us insight into how we can develop targeted therapies to address these tumors,” she says. “A better understanding of the science and biology behind how ATRTs develop is where the next advances will come from. That will give us another way to further tailor therapy for these patients.”

Request an appointment at MD Anderson online or call 1-855-942-1358.

Related Cancerwise Stories

Aggressive multimodality therapy is improving outcomes in this aggressive disease, but there is much room for improvement.

Susan McGovern, M.D., Ph.D.

Physician & Researcher