- Diseases

- Acoustic Neuroma (14)

- Adrenal Gland Tumor (24)

- Anal Cancer (66)

- Anemia (2)

- Appendix Cancer (16)

- Bile Duct Cancer (26)

- Bladder Cancer (68)

- Brain Metastases (28)

- Brain Tumor (230)

- Breast Cancer (718)

- Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (2)

- Cancer of Unknown Primary (4)

- Carcinoid Tumor (8)

- Cervical Cancer (154)

- Colon Cancer (164)

- Colorectal Cancer (110)

- Endocrine Tumor (4)

- Esophageal Cancer (42)

- Eye Cancer (36)

- Fallopian Tube Cancer (6)

- Germ Cell Tumor (4)

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (2)

- Head and Neck Cancer (6)

- Kidney Cancer (124)

- Leukemia (344)

- Liver Cancer (50)

- Lung Cancer (288)

- Lymphoma (284)

- Mesothelioma (14)

- Metastasis (30)

- Multiple Myeloma (98)

- Myelodysplastic Syndrome (60)

- Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (4)

- Neuroendocrine Tumors (16)

- Oral Cancer (100)

- Ovarian Cancer (170)

- Pancreatic Cancer (164)

- Parathyroid Disease (2)

- Penile Cancer (14)

- Pituitary Tumor (6)

- Prostate Cancer (144)

- Rectal Cancer (58)

- Renal Medullary Carcinoma (6)

- Salivary Gland Cancer (14)

- Sarcoma (236)

- Skin Cancer (296)

- Skull Base Tumors (56)

- Spinal Tumor (12)

- Stomach Cancer (60)

- Testicular Cancer (28)

- Throat Cancer (90)

- Thymoma (6)

- Thyroid Cancer (98)

- Tonsil Cancer (30)

- Uterine Cancer (78)

- Vaginal Cancer (14)

- Vulvar Cancer (18)

- Cancer Topic

- Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Issues (20)

- Advance Care Planning (10)

- Biostatistics (2)

- Blood Donation (18)

- Bone Health (8)

- COVID-19 (362)

- Cancer Recurrence (120)

- Childhood Cancer Issues (120)

- Clinical Trials (626)

- Complementary Integrative Medicine (24)

- Cytogenetics (2)

- DNA Methylation (4)

- Diagnosis (230)

- Epigenetics (6)

- Fertility (64)

- Follow-up Guidelines (2)

- Health Disparities (14)

- Hereditary Cancer Syndromes (124)

- Immunology (18)

- Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (8)

- Mental Health (118)

- Molecular Diagnostics (8)

- Pain Management (62)

- Palliative Care (8)

- Pathology (10)

- Physical Therapy (18)

- Pregnancy (18)

- Prevention (896)

- Research (390)

- Second Opinion (74)

- Sexuality (16)

- Side Effects (604)

- Sleep Disorders (10)

- Stem Cell Transplantation Cellular Therapy (216)

- Support (404)

- Survivorship (322)

- Symptoms (184)

- Treatment (1774)

7 things sarcoma patients should know about allografts

3 minute read | Published August 09, 2017

Medically Reviewed | Last reviewed by an MD Anderson Cancer Center medical professional on August 09, 2017

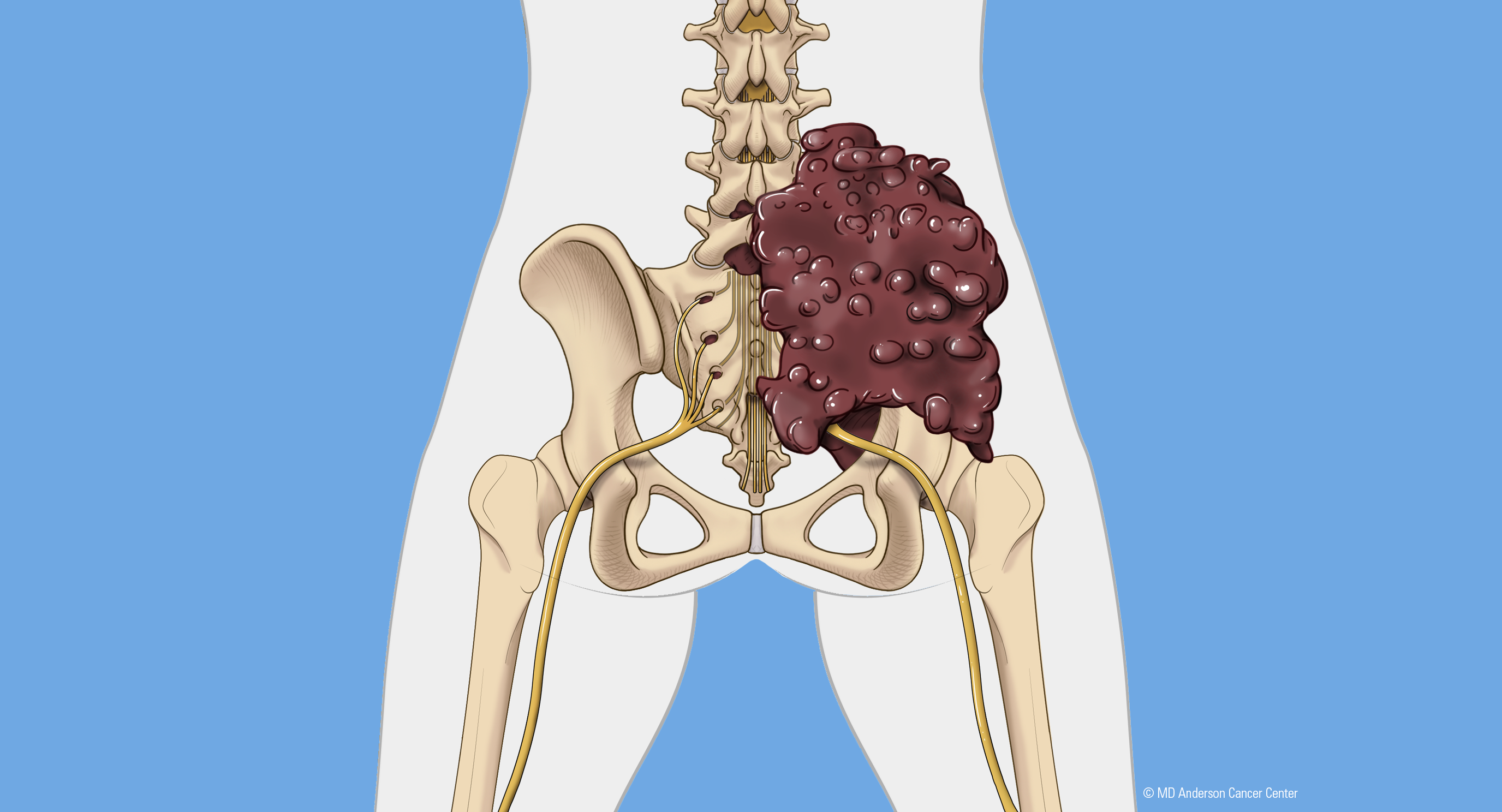

For Ewing’s sarcoma and other types of sarcomas, treatment can sometimes include surgery to remove a tumor. That can also mean removing part — or even all — of the bone it’s attached to. Options for replacing a lost bone include metal implants called endo-prostheses, autografts (bones that come from the patients themselves) and allografts (bones from donors).

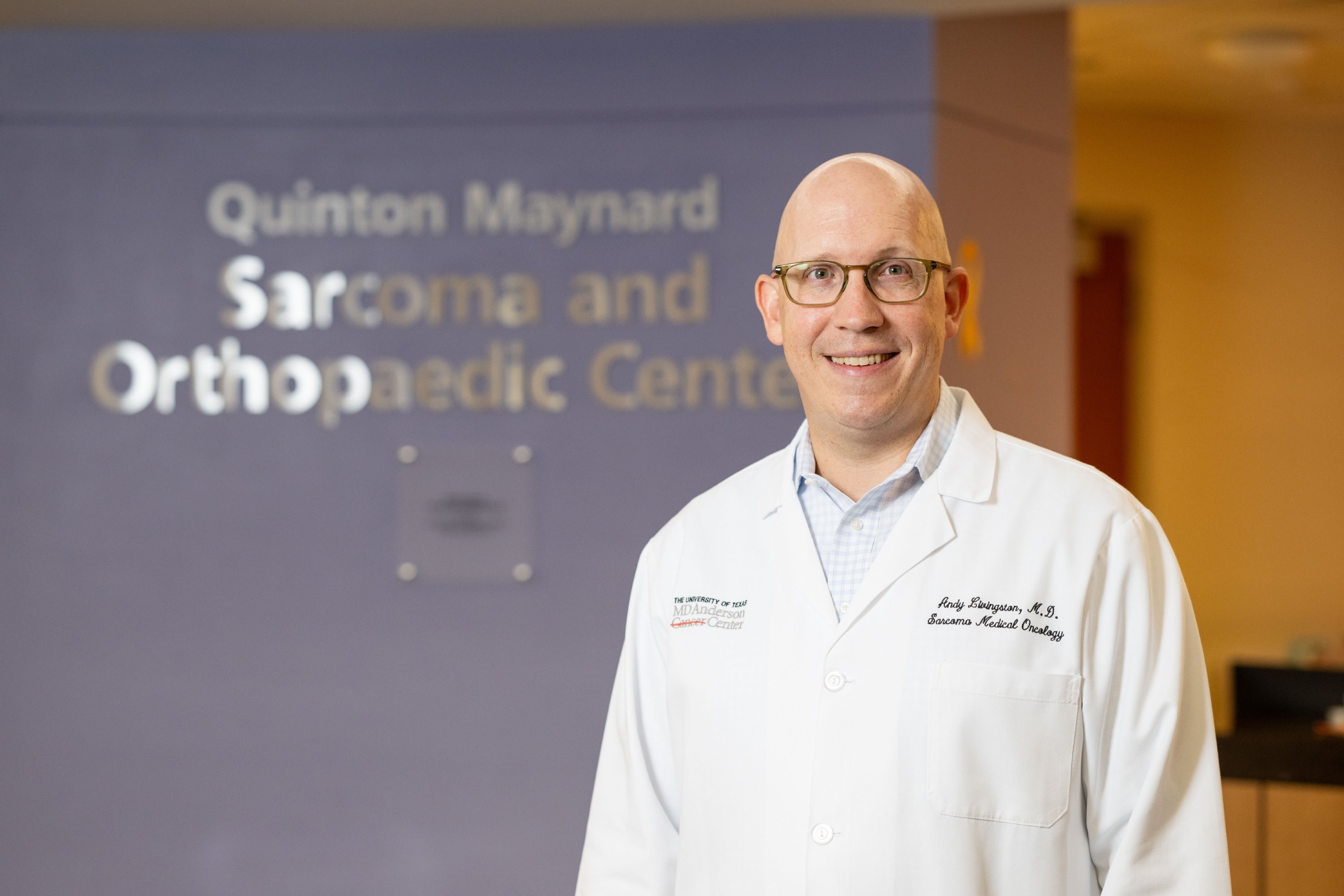

Here, Justin Bird, M.D., shares seven things he wants you to know about allografts.

Where does MD Anderson get the donor bones for its allografts?

There are a few companies that source specimens, prepare them for use, and make them available to doctors and hospitals.

Do the bones come from people who have donated their bodies to science?

No. They come from organ donors. Tissue banks are able to use many different types of donated organs, including bones, for transplants.

Does a patient’s blood type have to match the donor’s in order to receive an allograft?

No. All living cells are removed from the bones before they’re used, so the patient’s body just treats them as a structure to grow on. That said, we do try to choose allografts that best match the patient’s height, size, gender and build.

Why would a patient elect to get an allograft rather than, say, an endo-prosthesis?

There are a number of reasons, including the location of the affected bone in the body and the involvement of soft tissue. In the early days of endo-prosthetics, there was nothing to help a bone hold onto a metal surface when you used an implant to repair a bone defect. Now, we have metal surface options with porous coatings. Living bone sees the small holes in the metal as opportunities for in-growth. But there are some challenges associated with attaching various structures (such as a tendon) to metal, so we still use allografts in some situations.

How do you know when an allograft is successful?

We get X-rays and CT scans to look for healing between the allograft and patient’s bone. Allografts work because the body treats them like scaffolding. It can recognize that type of structure and grow into it. A patient’s tissue won’t grow through the entire thing, but if we can get that healing at the edges, it’s enough to maintain the structural integrity of a reconstruction.

Is it possible for patients to get a bone graft from themselves?

Yes, that’s called an autograft. Tumors can show up in any part of the skeleton, so surgeons may have the option of taking part of a non-weight-bearing bone from the patient to reconstruct what was removed. The fibula is a very good donor bone. It’s the smaller of the two leg bones below the knee, and it’s non-weight-bearing, so we can remove it without causing significant functional changes.

What types of advances are you seeing in this field?

Our plastic surgeons are experts in vascularized bone grafts, which come from the patients themselves. We take a bone — again, usually the fibula — along with its blood supply, and use it to repair defects in the spine, pelvis, mandible or other areas. Orthopedic surgeons place the graft where they want it, and then plastic surgeons sew the blood vessels together at the new site. Moving the bone along with its blood supply helps patients heal much faster.

Request an appointment at MD Anderson online or by calling 1-844-598-6804.

Related Cancerwise Stories

Allografts work because the body treats them like scaffolding.

Justin Bird, M.D.

Physician