Diet soda and cancer risk: What you should know

Diet soda has few, if any, calories. So, you may think it’s a healthier, waist-shrinking alternative to regular soda. But that’s not the case.

Research shows that people who drink diet beverages consume significantly more calories from food than people who drink sugar-sweetened beverages, like regular soda. These extra food calories can add up to a higher number on your bathroom scale. And people with obesity or higher weights are at increased risk for more than 10 types of cancer.

Invasive ductal carcinoma: 6 things to know about this common breast cancer

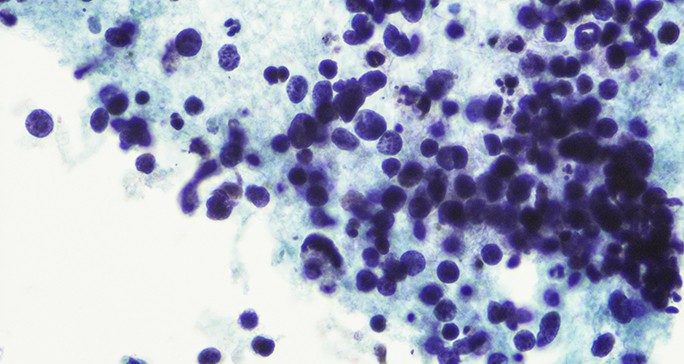

What can a pathology report tell you?

Gynecologic oncologist: Why I’m passionate about cancer care at MD Anderson

Diet soda and cancer risk: What you should know

What are the symptoms of liposarcoma?

Personalized treatment helps retired physician overcome dual cancer diagnoses

|

$entity1.articleCategory

|

|---|

|

$entity2.articleCategory

|

|

$entity3.articleCategory

|

|

$entity4.articleCategory

|

|

$entity5.articleCategory

|

|

$entity6.articleCategory

|

Find stories by topic

Find out everything you need to know to navigate a cancer diagnosis and treatment from MD Anderson’s experts.

What can a pathology report tell you?

April 10, 2025

What are the symptoms of liposarcoma?

April 08, 2025

Cancer treatment side effect: Muscle cramps

April 03, 2025

What types of cancer can cause itchy skin?

March 24, 2025

Read inspiring stories from patients and caregivers – and get their advice to help you or a loved one through cancer.

Music to a mother’s ears: Awake craniotomies bring musicians together

February 24, 2025

Art Space volunteer draws inspiration from young friend

January 31, 2025

Get MD Anderson experts’ advice to help you stay healthy and reduce your risk of diseases like cancer.

Diet soda and cancer risk: What you should know

April 09, 2025

How to get your heart rate up

April 04, 2025

What happens when you overeat?

April 01, 2025

How to make colonoscopy prep better

March 31, 2025

Negative effects of vaping on teens

March 28, 2025

How to avoid injury when starting a new exercise routine

March 19, 2025

How to clean your ears safely: Tips to avoid harm

March 17, 2025

Learn how MD Anderson researchers are advancing our understanding and treatment of cancer – and get to know the scientists behind this research.

How non-scientists are helping cancer researchers

February 21, 2025

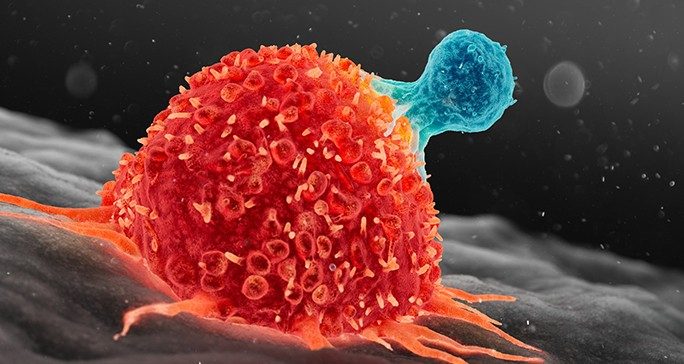

4 questions with immunology researcher Susan Bullman

February 04, 2025

4 questions for mathematical oncologist Heiko Enderling, Ph.D.

January 28, 2025

Committed to making cervical cancer screening easier

January 08, 2025

11 new research advances from the past year

December 19, 2024

Finding hope for cancer patients in ferroptosis research

December 12, 2024

Advances in small cell lung cancer classification

November 25, 2024

Exploring pancreatic cancer vaccines: What’s next?

November 21, 2024

Read insights on the latest news and trending topics from MD Anderson experts, and see what drives us to end cancer.

How to take medications properly: 6 questions, answered

February 28, 2025

Clinical Ethics Fellow passionate about improving patient care

February 27, 2025

Senior speech pathologist: Patients are my No. 1 priority

February 19, 2025

Motivated to do more for pediatric patients

February 18, 2025

Leukemia nurse fulfills promise to her late mother

February 17, 2025

Find out what inspires our donors to give to MD Anderson, and learn how their generous support advances our mission to end cancer.

Three cancer survivors raise funds to support Colorado patients

October 03, 2024

Inflammatory breast cancer survivor finds hope at MD Anderson

October 24, 2023