Questions to ask your doctor when transitioning to cancer survivorship care

At MD Anderson, you’re considered a survivor from the day of your cancer diagnosis. And after you’ve completed primary cancer treatment, you transition to survivorship. Essentially, this is your life after cancer. And it includes specialized survivorship care.

Survivorship care is focused on maximizing your health and well-being after cancer. This includes assessing for any late cancer recurrence as well as managing and reducing late or long-term side effects.

When should you worry about your menstrual cycle?

Questions to ask your doctor when transitioning to cancer survivorship care

Nutrivention: Food as medicine

7 things to know about myelofibrosis

|

$entity1.articleCategory

|

|---|

|

$entity2.articleCategory

|

|

$entity3.articleCategory

|

|

$entity4.articleCategory

|

|

$entity5.articleCategory

|

|

$entity6.articleCategory

|

Find stories by topic

Find out everything you need to know to navigate a cancer diagnosis and treatment from MD Anderson’s experts.

When should you worry about your menstrual cycle?

June 02, 2025

7 things to know about myelofibrosis

May 27, 2025

Cancer of the jaw: 8 things to know

May 21, 2025

Which blood tests show cancer?

May 19, 2025

What are polyps?

May 13, 2025

Read inspiring stories from patients and caregivers – and get their advice to help you or a loved one through cancer.

Mom's legacy lives on through fundraising for MD Anderson

April 28, 2025

Get MD Anderson experts’ advice to help you stay healthy and reduce your risk of diseases like cancer.

What SPF should I use?

May 23, 2025

Is raw milk safe?

May 16, 2025

How much caffeine is too much?

May 09, 2025

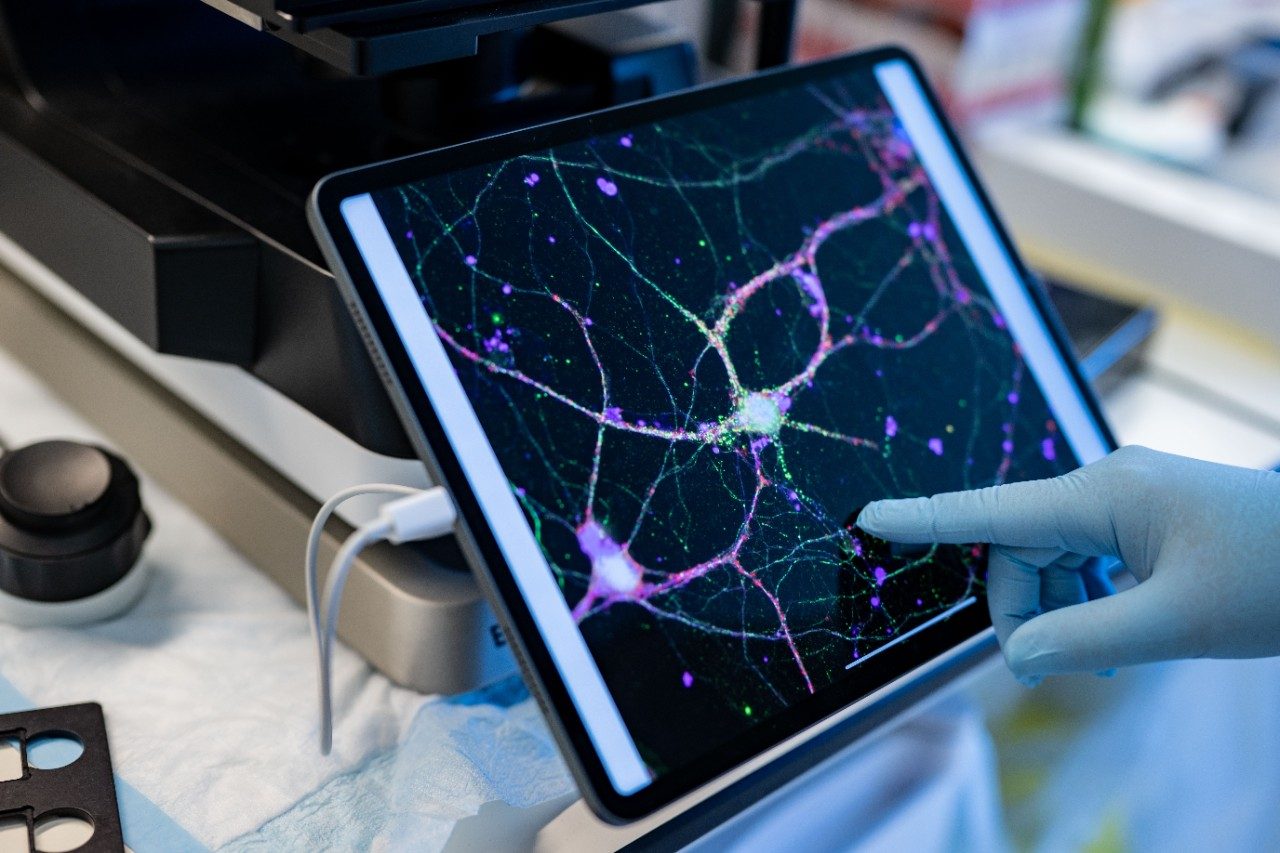

Learn how MD Anderson researchers are advancing our understanding and treatment of cancer – and get to know the scientists behind this research.

Nutrivention: Food as medicine

May 28, 2025

5 emerging therapies presented at ASCO 2025

May 28, 2025

Top 5 MD Anderson abstracts at AACR 2025

April 25, 2025

Cell therapy: The evolution of the ‘living drug’

April 22, 2025

How non-scientists are helping cancer researchers

February 21, 2025

4 questions with immunology researcher Susan Bullman

February 04, 2025

4 questions for mathematical oncologist Heiko Enderling, Ph.D.

January 28, 2025

Committed to making cervical cancer screening easier

January 08, 2025

Read insights on the latest news and trending topics from MD Anderson experts, and see what drives us to end cancer.

Surgeon-scientist: ‘MD Anderson is unique’

May 15, 2025

Find out what inspires our donors to give to MD Anderson, and learn how their generous support advances our mission to end cancer.

Mom's legacy lives on through fundraising for MD Anderson

April 28, 2025

Three cancer survivors raise funds to support Colorado patients

October 03, 2024

Inflammatory breast cancer survivor finds hope at MD Anderson

October 24, 2023