Young adult cancer pre-vivor: Why I had my stomach removed at age 25

Most people don’t realize you can live quite comfortably without a stomach. But I found that out first-hand in 2020, after learning I carry a genetic mutation called CDH1.

CHD1 dramatically increases your risk of developing both stomach cancer and lobular carcinoma, a type of breast cancer. The risk is so high for stomach cancer that doctors often recommend a total gastrectomy — or the complete surgical removal of your stomach — as a preventive measure. Once the stomach tissue is biopsied, pathologists often find that cancer cells are already present.

Cancer of the jaw: 8 things to know

Can sitting for too long really increase your cancer risk?

Young adult cancer pre-vivor: Why I had my stomach removed at age 25

Which blood tests show cancer?

Is raw milk safe?

Surgeon-scientist: ‘MD Anderson is unique’

|

$entity1.articleCategory

|

|---|

|

$entity2.articleCategory

|

|

$entity3.articleCategory

|

|

$entity4.articleCategory

|

|

$entity5.articleCategory

|

|

$entity6.articleCategory

|

Find stories by topic

Find out everything you need to know to navigate a cancer diagnosis and treatment from MD Anderson’s experts.

Cancer of the jaw: 8 things to know

May 21, 2025

Which blood tests show cancer?

May 19, 2025

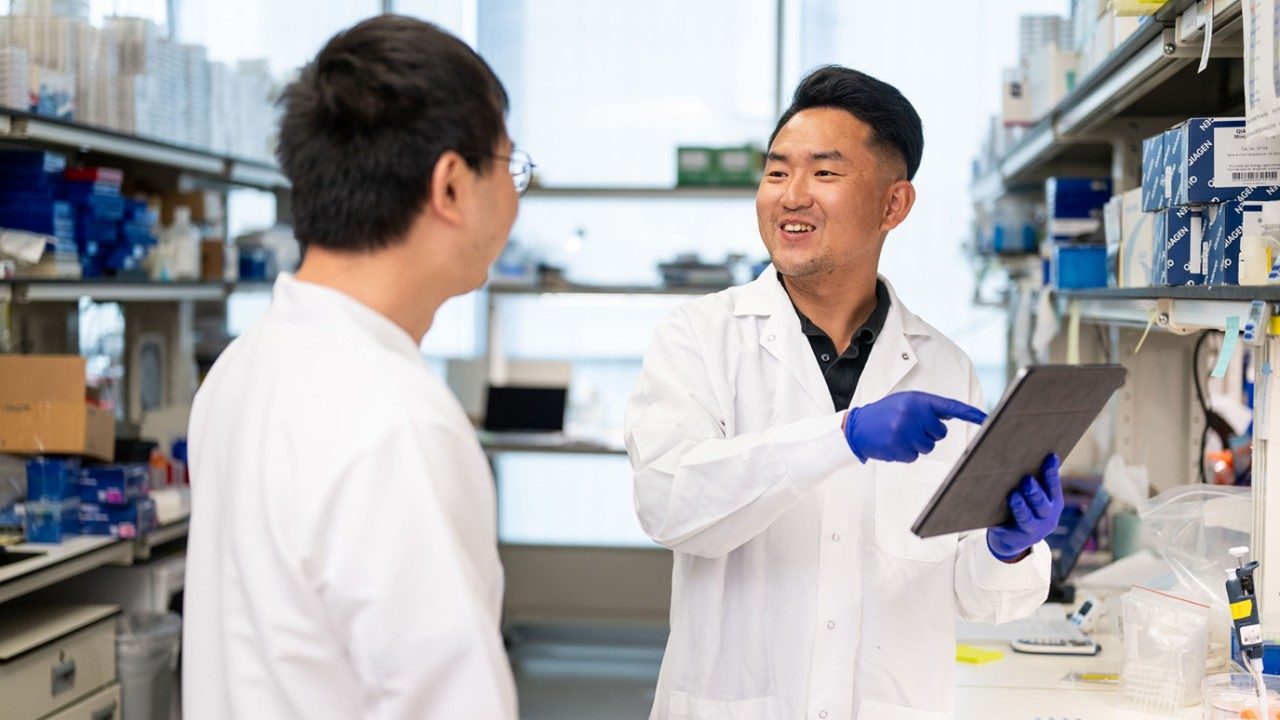

Surgeon-scientist: ‘MD Anderson is unique’

May 15, 2025

What are polyps?

May 13, 2025

PET scans: What are they and what to expect

May 02, 2025

Read inspiring stories from patients and caregivers – and get their advice to help you or a loved one through cancer.

Mom's legacy lives on through fundraising for MD Anderson

April 28, 2025

Get MD Anderson experts’ advice to help you stay healthy and reduce your risk of diseases like cancer.

Is raw milk safe?

May 16, 2025

How much caffeine is too much?

May 09, 2025

Beef tallow benefits: Should you use it?

May 06, 2025

Do GMOs cause cancer?

May 01, 2025

Detoxes, cleanses and fasts: What you should know

April 29, 2025

Learn how MD Anderson researchers are advancing our understanding and treatment of cancer – and get to know the scientists behind this research.

Top 5 MD Anderson abstracts at AACR 2025

April 25, 2025

Cell therapy: The evolution of the ‘living drug’

April 22, 2025

How non-scientists are helping cancer researchers

February 21, 2025

4 questions with immunology researcher Susan Bullman

February 04, 2025

4 questions for mathematical oncologist Heiko Enderling, Ph.D.

January 28, 2025

Committed to making cervical cancer screening easier

January 08, 2025

11 new research advances from the past year

December 19, 2024

Finding hope for cancer patients in ferroptosis research

December 12, 2024

Read insights on the latest news and trending topics from MD Anderson experts, and see what drives us to end cancer.

How to take medications properly: 6 questions, answered

February 28, 2025

Find out what inspires our donors to give to MD Anderson, and learn how their generous support advances our mission to end cancer.

Mom's legacy lives on through fundraising for MD Anderson

April 28, 2025

Three cancer survivors raise funds to support Colorado patients

October 03, 2024

Inflammatory breast cancer survivor finds hope at MD Anderson

October 24, 2023