A closer look at cancer screening guidelines

If the release of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations on screening has taught us anything, it’s that not all cancer screening guidelines are created equal.

Age, gender, lifestyle and even genetics play a role in a person’s need to be screened for cancer. Considering the different factors that can contribute to a person’s risk of developing cancer, these guidelines are not only important, but also necessary.

In 2009, when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released recommendations that routine breast cancer screenings should start at age 50 instead of 40 — and women should then only have biennial screening mammograms until age 74 — a media storm emerged. This included not only outcries from clinicians and health care providers across the country, but also from patients, survivors and family members.

Just last year, the same task force sought public input on a draft document that recommended against the use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests in men to detect prostate cancer, claiming it may do more harm than good. Although the recommendation was targeted toward healthy men, many patient advocates and some health care providers thought differently, and there was another public outcry.

Evidence-based guidelines

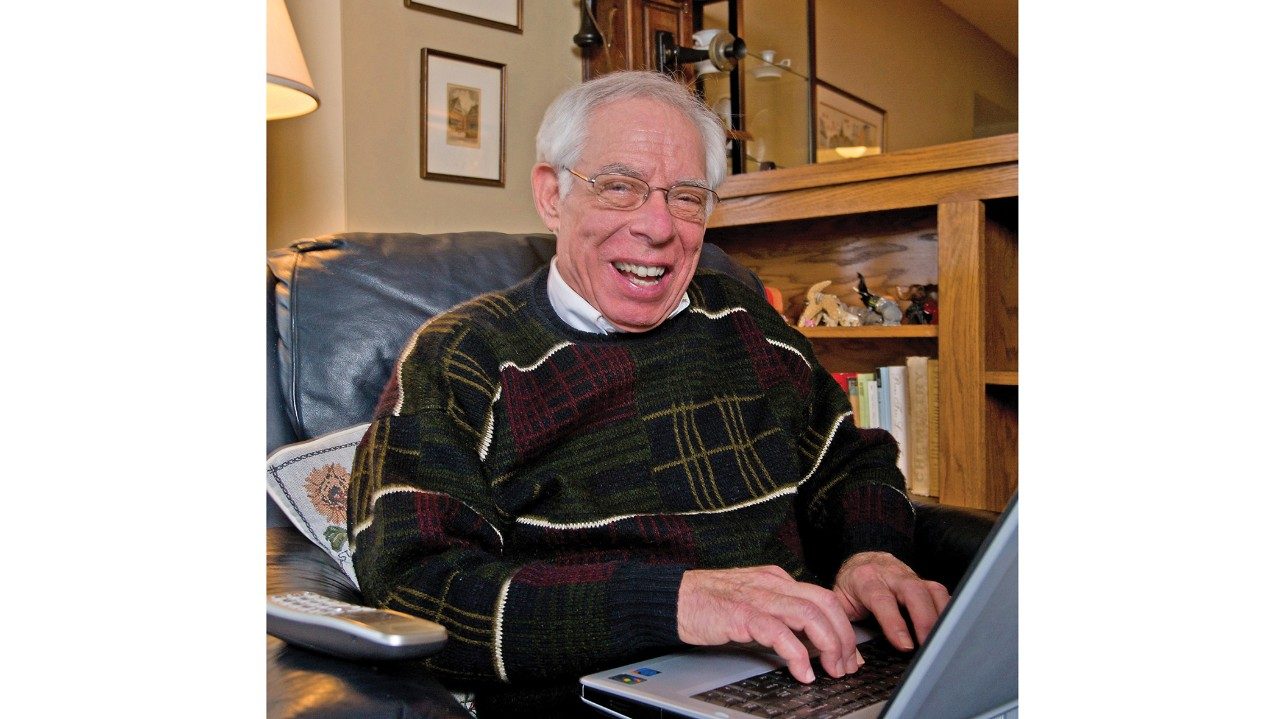

Therese Bevers, M.D., professor in MD Anderson’s Department of Clinical Cancer Prevention and medical director of its Cancer Prevention Center, knows only too well the careful thought that goes into developing screening guidelines — and the influence it can have on a person’s decision to be screened.

Bevers is at the helm of MD Anderson’s clinical workgroups that develop, approve and implement the institution’s cancer screening guidelines or “algorithms.”

“We develop our own institutional algorithms according to best practices, and the guidelines are evidence-based,” Bevers says. “Our guidelines do not always mirror other institutional and national task force recommendations.”

Bevers, who emphasizes that early detection is the key to fighting breast cancer, stands behind MD Anderson’s breast cancer screening guidelines that recommend annual mammograms for women at average risk, starting at age 40.

Managing care through clinical effectiveness

Algorithms are developed based on best practices, using the available evidence in combination with consensus of expert opinion. Bevers works with the Department of Clinical Effectiveness, whose main goal is to enhance the delivery of safe, effective and consistent health care to patients across the continuum of care.

The department focuses on the development, maintenance and evaluation of evidence-based patient care management tools for cancer treatment, as well as tools for cancer screening, clinical management and survivorship.

“All patient care management tools are developed, reviewed and approved by the medical staff,” says Yvette DeJesus, director of the department. “It’s our way of ensuring that checks and balances are in place to provide the best possible outcomes for our patients and potential patients.”

United we stand

As the physician champion of the various clinical workgroups that develop the cancer screening algorithms, Bevers’ involvement is multidimensional. She follows each one through its process.

- Step one: The Clinical Effectiveness Subcommittee creates a workgroup of multidisciplinary experts in the disease whose algorithm is being developed.

- Step two: The Clinical Effectiveness Subcommittee reviews and recommends the algorithm, then submits it to the Medical Practice Committee for approval.

- Step three: The Executive Committee of the Medical Staff gives final approval, which means the algorithm represents best practices at MD Anderson.

- Step four: The Department of Clinical Effectiveness ensures all algorithms, including cancer screening, are reviewed annually.

Re-examining the old and ushering in the new

MD Anderson’s focus on cancer prevention for the past 15 years has led to the development of algorithms for a variety of cancers. Last year, new screening algorithms were developed for lung, skin, ovarian and endometrial cancers. This year, in addition to updating the previously developed cancer screening algorithms, the institution plans to unveil new screening algorithms for prostate and liver cancers.

“Since every cancer is different and people are at different levels of risk, cancer screening guidelines offer guidance for people to make the best decisions about their health,” Bevers says.

Need for Endometrial Screening Guidelines

With the release of the new cancer prevention screening algorithms, Jubilee Brown, M.D., associate professor in the Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, is anticipating an opportunity to educate the public about endometrial cancer.

Brown notes that more than 47,000 new cases of endometrial cancer are expected in the United States this year.

“Currently, there’s no benefit to biopsy or transvaginal ultrasounds for women at average risk,” Brown says. “It’s important for us to educate women on the risk factors and on how to recognize the early warning signs of this cancer.”

Obesity is the number one risk factor for developing endometrial cancer. Early warning signs can include abnormal bleeding and vaginal discharge. Brown encourages women with symptoms to see a doctor as soon as possible.