Institutional Review Board ensures patient safety

In 2004, James Yao, M.D., learned that one patient can open a whole new world of possibilities.

After examining a young woman with two rare diseases, the associate professor in the Department of Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology at MD Anderson asked himself: “Are there similarities in the two that might present a treatment target?”

That was the beginning of the quest that led him to everolimus.

But it would take seven years of clinical trials with solid findings before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug for the treatment of cancer patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNET).

There are safeguards that govern clinical trials and protect patients.

‘Do no harm’

Since the 5th century BCE, patient safety has been an essential concern of physicians.

“I will prescribe regimens for the good of my patients according to my ability and my judgment and never do harm to anyone,” the original Hippocratic oath clearly states.

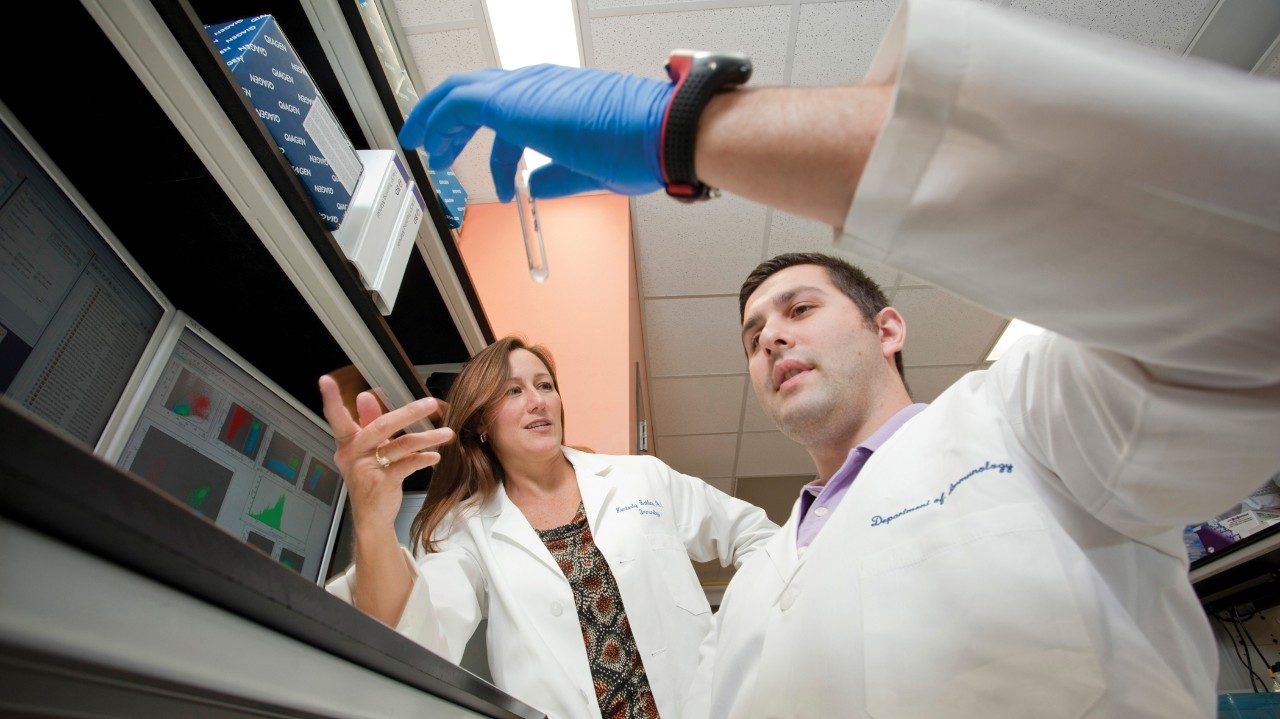

This is especially important in the case of clinical trials, such as Yao’s. To protect patients who enter these studies, the FDA and the Office of Human Research Risk Protection require that potential studies go through an Institutional Review Board (IRB). MD Anderson has five to handle the volume of research. But exactly what do they do and why are they important?

“The IRB’s purpose is to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects recruited to advance medical knowledge,” says Aman Buzdar, M.D., professor in MD Anderson’s Department of Breast Medical Oncology and ad interim vice president for clinical research. “It minimizes patient risk, reviews informed consents, oversees the risk-versus-benefit ratio of each research proposal and assures a patient’s confidentiality.”

From Easter Island to MD Anderson

Yao took each of these steps to ensure the safety and efficacy of everolimus for pNET patients. Here is the story from the discovery of the drug to its current status.

1970s: A bacterial strain, isolated from an Easter Island soil sample, is found to have immunosuppressive properties and is developed as an organ transplant rejection drug.

November 2002: Investigation of everolimus as a cancer treatment begins.

Early 2004: Yao observes a patient with two rare diseases — pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (pNET) and tuberous sclerosis, a multi-system genetic disease that causes several types of tumors to grow in the body’s organs. He discovers that both have malfunctions in the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway.

2004: Yao talks with Novartis, the pharmaceutical company that markets everolimus for cancer patients under the trade name Afinitor®.

2004: Novartis finds the protocol interesting, but not enough to completely back it. It offers the drug and partial financial support to do an MD Anderson study.

Late 2004: Yao and his colleagues write the protocol for a Phase II clinical trial, which is first reviewed by the Clinical Research Committee, then goes to the IRB. This is a small study to accrue 40 patients at a low dose of 5 mg of everolimus to test for safety.

January 2005: The first patients are enrolled in the study. Positive results — the tumors of the first three patients show shrinkage — pique everyone’s interest.

August 2005: Yao and his group apply to the IRB to expand the study. Issues weighed are: increasing enrollment to 70 patients; creating two study arms, one for patients with pNET, the other for patients with non-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors; and raising the dosage to 10 mg.

2005: Everolimus goes back to the laboratory for translational research. Biopsies from patients in each arm are paired to learn more about how the drug works and to see changes in tissue before and after treatment.

December 2005: The IRB approves the amended protocol. The trial opens to accrue more patients.

2005: The IRB approves a small, follow-up Phase II study for 36 patients, combining everolimus with bevacizumab (Avastin®).

August 2007-May 2009: A multinational Phase III randomized study of everolimus versus a placebo begins, after IRB approval. This offers cross-over possibilities for patients whose cancer progressed. An independent data safety monitoring committee oversees the study to ensure safety.

June 1, 2010: Yao receives an email stating that the pivotal Phase III study shows everolimus decreased the risk of tumor growth by 65%.

May 2011: FDA approves everolimus for the treatment of pNET.

Building on the knowledge gained by Yao and others, multiple clinical trials with everolimus — on its own and in combination — are being conducted worldwide for various types of cancer.

Clinical trials are instrumental in defining the new boundaries of medicine, but first and foremost, at all times, is the protection of patients’ rights and safety. As for the young woman whose condition led to the discovery of everolimus for treatment of pNET, she underwent surgery and is potentially cured from her pancreatic neuroendocrine cancer.