Going deep into the science of improvement

New-generation research strives to achieve best value for cancer care

Ask survivors to place a value on a future free from cancer, and they will say it’s priceless.

Put the question to a growing number of faculty and employees, and many will point to a wide range of initiatives designed to define, measure, share — and improve — the value of MD Anderson care.

“Value is defined as cost of care as a function of the desired outcome — achieving the best possible outcome for the patient’s cancer at the lowest cost necessary to achieve that desired outcome,” says Randal Weber, M.D., professor and chair of the Department of Head and Neck Surgery.

Known as “the science of improvement,” this new dimension of research is helping prepare the institution for an era of health care laws, reduced reimbursements, tougher competition and a mandate for public transparency. Such research and data also can drive policy, improve care and enhance patient satisfaction.

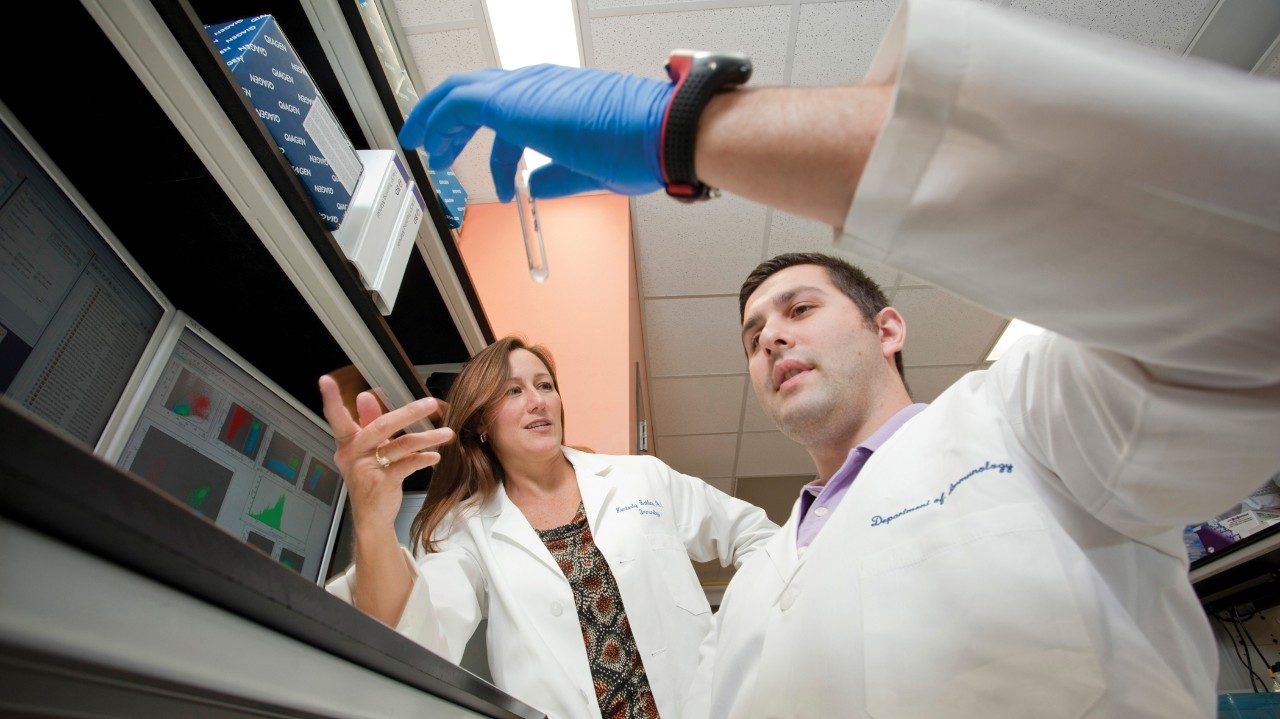

Working in partnership with MD Anderson’s quality and performance improvement groups, the Institute for Cancer Care Excellence (ICCE) has launched initiatives to look for ways to eliminate waste, reduce costs, quantify quality care and increase revenues. It’s new-generation research that goes behind the scenes, often dissecting costs, processes and data, but always focusing on the patient.

“It’s a question that consumers, insurance companies and payers such as Medicare ask now. In the future, they will press for answers,” says Thomas Feeley, M.D., who heads the ICCE and is professor and head of the Division of Anesthesiology and Critical Care.

“Like the clinical research for which MD Anderson is renowned, these teams are asking a new version of the old question.”“What’s a better way of providing care and how do we prove it’s better?”

Here’s a sampling of how MD Anderson is addressing some of these value questions:

Process metrics

Outcomes reporting is among the measurements mandated in 2014 as part of health care legislation. In its effort to understand what people want, MD Anderson talked first to patients and survivors about how they might have used outcomes information when deciding where to seek treatment.

Most said they chose MD Anderson because of the institution’s reputation. Of these, many did not have data on which to make an informed decision, while some indicated that knowing survival rates might even have added to their anxiety.

Those who sought data stated they would have wanted to have information on case volume, medical team experience and procedure complication rate.

In 2014, MD Anderson will report five process metrics in accordance with legislation: three related to cancer treatment and two others related to rates of hospital-acquired infections.

Cutting waste, funneling savings

One institutional workgroup is chaired by Marshall Hicks, M.D., professor and head of the Division of Diagnostic Imaging. This group strives to funnel cost savings into new technologies, services, programs and people vital to MD Anderson’s mission.

One result is a built-in electronic “flag” that alerts clinical employees to get a pre-approval from payers for a diagnostic test. Adding this small step to the electronic order entry meant millions of dollars in write-offs were averted in Fiscal Year 2011.

A similar solution arose when the group looked at write-offs for a commonly used — and expensive — targeted therapy. Instead of physicians continuing to use the drug for extended periods of time, the group added an electronic “hard stop” to an order entry that prompts conversations between physician and pharmacist.

Quality care, better outcomes

Ehab Hanna, M.D., professor in the Department of Head and Neck Surgery, and his team are building on what they have learned from ICCE’s success in defining and measuring value for many patients in the Head and Neck Center.

They chose several questions to define quality care for patients diagnosed with throat, mouth and voice box cancers. They studied 2,368 patients and looked at the responses related to a patient’s survival and the ability to swallow, breathe and speak. While eating and speaking are generally assumed to improve quality of life, the team discovered that they needed to re-evaluate processes for gathering data. Each step is another valuable lesson learned.

“The nation’s economic downturn made us realize our structure was fragile. With the changes in health care coming, it made sense to be ready in every area of the institution,” says Stephen Swisher, M.D., professor and chair of the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. He led a group charged with developing new ways to increase revenues.

“During a financial crisis you go into survival mode, but this is our opportunity to bring together a multidisciplinary team to reduce costs, measure quality and infuse revenue opportunities in a valid and thoughtful way, always keeping the optimum care of the cancer patient as our top priority,” Swisher says.