A step toward personalized breast cancer medicine

Preclinical study changes p53 paradigm

Presence of the normal p53 gene, rather than a mutated version, makes breast cancer chemotherapy with doxorubicin less effective, MD Anderson scientists report in the journal Cancer Cell.

Their preclinical study challenges the existing paradigm and marks another step toward personalized medicine for breast cancer.

p53, a tumor suppressor, is mutated or inactivated in the majority of cancers, and about one-third of breast cancers have mutations in the gene. It’s long been thought that normal p53 results in a better chemotherapy response, but the evidence in breast cancer has been conflicting.

The scientists first examined the response to doxorubicin in mice and the role of p53 in the chemotherapy process. When they analyzed the results, they found the mice that responded poorly had normal p53 genes, while the mice that responded best had mutated p53 genes.

Using human breast tumor cell lines with normal p53, the researchers replicated the mouse experiment with the same results. When the cells were treated with doxorubicin, known commercially as Adriamycin®, they basically stopped. When the p53 gene was removed, the cells continued through the cell cycle and eventual destruction.

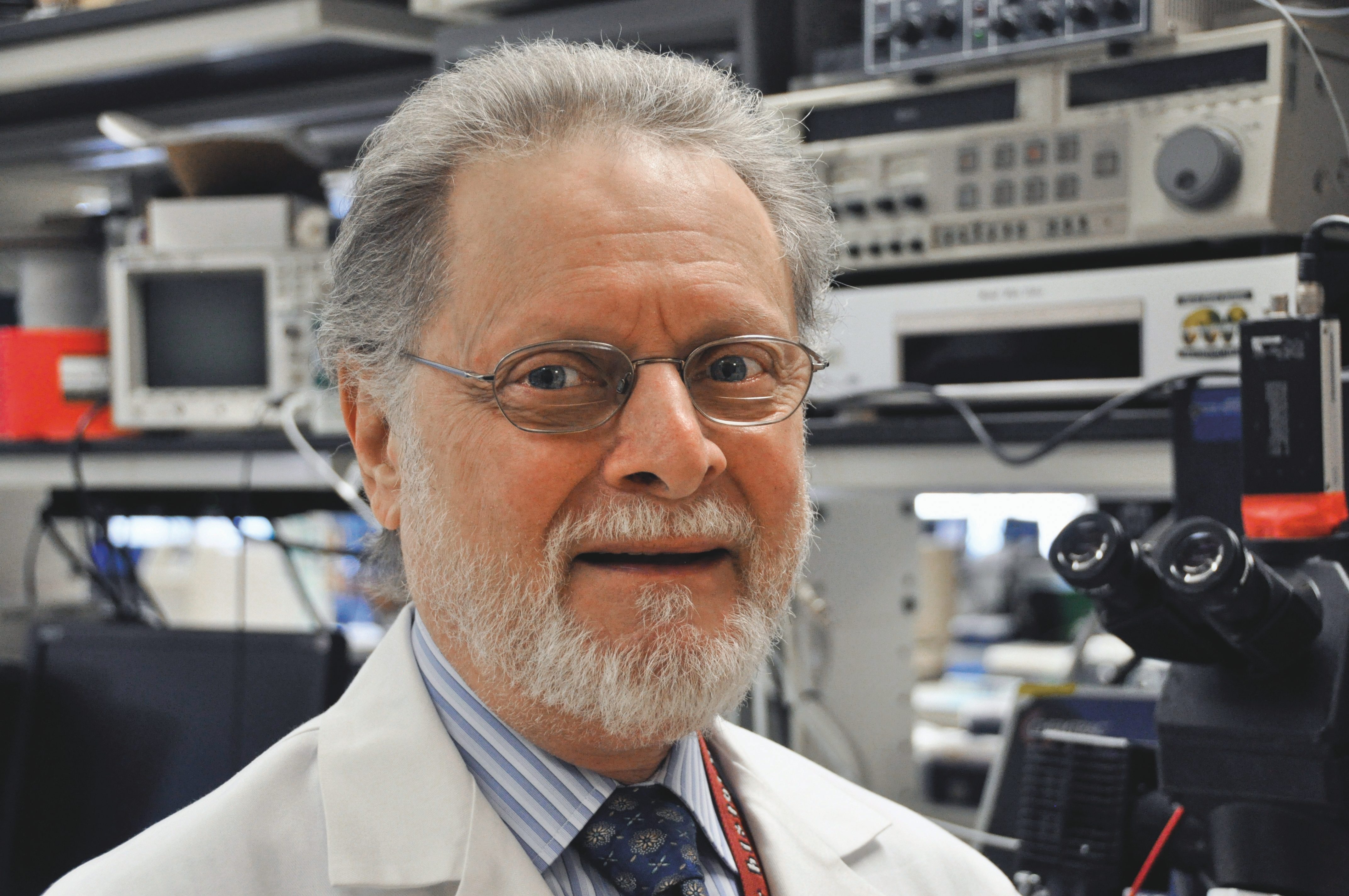

“There are a lot of data out there on responses to doxorubicin and other drugs that break DNA,” says lead author Guillermina Lozano, Ph.D., professor and chair of MD Anderson’s Department of Genetics. “The response rates were mixed, and we never understood the difference. Now we understand that we need to know the p53 status to predict a response.”

This project was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health, a Theodore N. Law Endowment for Scientific Achievement and a Dodie P. Hawn Fellowship in Cancer Genetics Research.