What is a case manager navigator?

Navigating the transition from hospital to home can be complex, especially for cancer patients whose care often continues well beyond discharge. At MD Anderson, case manager navigators support patients and families throughout their inpatient stays while preparing them for life after leaving the hospital.

MD Anderson has over 70 full-time case manager navigators, all of whom are registered nurses. Their behind-the-scenes clinical support, care coordination and discharge planning ensure each patient receives the right care at the right time in the right setting.

Is fatty liver disease increasing your cancer risk?

What is a case manager navigator?

Breast cancer recurrence: Which types of breast cancer are most likely to come back?

What are chemo curls? Understanding post-chemo hair changes

5 barriers to diet change and how to overcome them

Second opinion, rare interventional radiology procedure save stage IV pancreatic cancer patient

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

|---|

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

|

Healthy Living

|

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

Find stories by topic

Find out everything you need to know to navigate a cancer diagnosis and treatment from MD Anderson’s experts.

What is a case manager navigator?

July 22, 2025

Should you be getting regular mental health checkups?

July 07, 2025

10 thyroid myths you shouldn’t believe

July 02, 2025

Read inspiring stories from patients and caregivers – and get their advice to help you or a loved one through cancer.

Astrocytoma survivor gives back to MD Anderson

July 03, 2025

Lymphoma survivor uses AI to help explain her treatment

June 20, 2025

Get MD Anderson experts’ advice to help you stay healthy and reduce your risk of diseases like cancer.

Is fatty liver disease increasing your cancer risk?

July 22, 2025

5 barriers to diet change and how to overcome them

July 17, 2025

Alcohol affects sleep – here's how

July 15, 2025

How can you tell if a mole is cancerous?

July 11, 2025

Can breastfeeding really lower your breast cancer risk?

July 08, 2025

Is BMI the best body weight calculator?

July 01, 2025

5 little-known breast cancer facts

June 24, 2025

What should you look for in a sun hat?

June 19, 2025

Learn how MD Anderson researchers are advancing our understanding and treatment of cancer – and get to know the scientists behind this research.

Using math to answer cancer’s biggest questions

July 09, 2025

What causes chemobrain? New insights

June 03, 2025

Nutrivention: Food as medicine

May 28, 2025

5 emerging therapies presented at ASCO 2025

May 28, 2025

Top 5 MD Anderson abstracts at AACR 2025

April 25, 2025

Cell therapy: The evolution of the ‘living drug’

April 22, 2025

How non-scientists are helping cancer researchers

February 21, 2025

Read insights on the latest news and trending topics from MD Anderson experts, and see what drives us to end cancer.

Tips for using AI to find cancer information

July 10, 2025

What is a Living Will?

June 06, 2025

Surgeon-scientist: ‘MD Anderson is unique’

May 15, 2025

Find out what inspires our donors to give to MD Anderson, and learn how their generous support advances our mission to end cancer.

Mom's legacy lives on through fundraising for MD Anderson

April 28, 2025

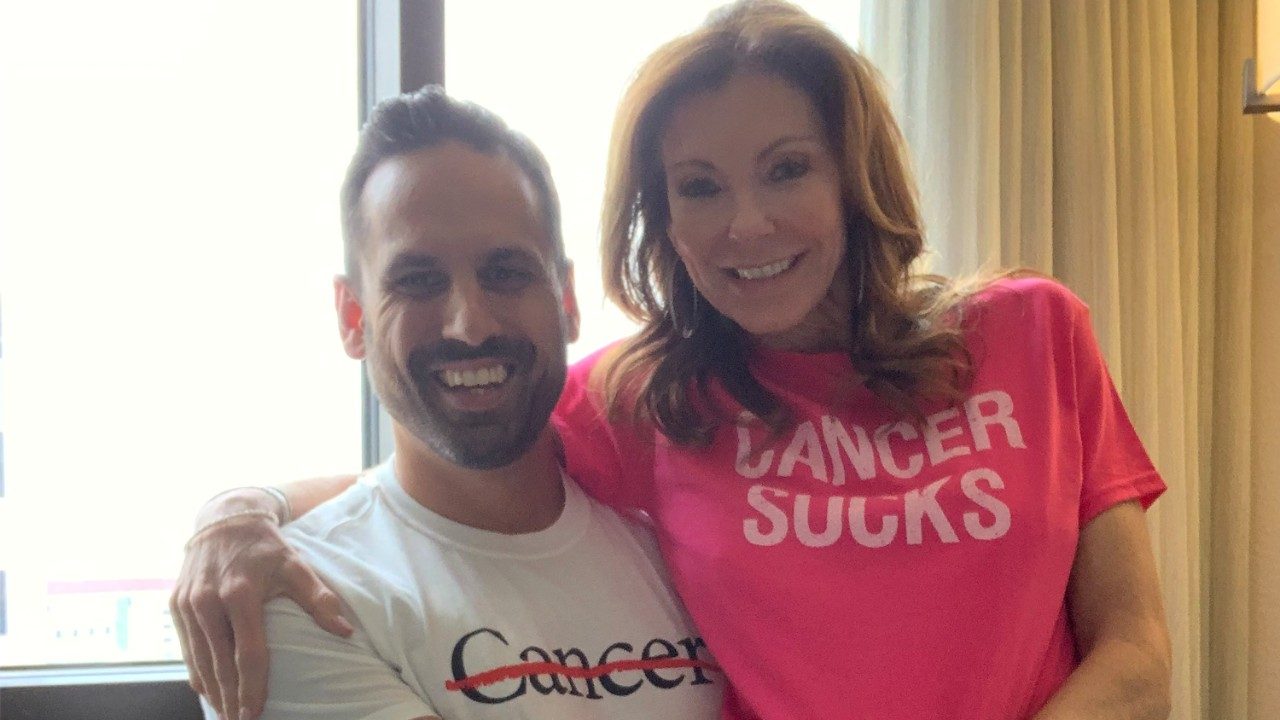

Three cancer survivors raise funds to support Colorado patients

October 03, 2024

Inflammatory breast cancer survivor finds hope at MD Anderson

October 24, 2023