The cancer prevention vaccine

Close to 80 million people in America currently are infected with the human papillomavirus, more commonly known as HPV. MD Anderson doctors are working to stop HPV-related diseases by increasing awareness and accessibility to what some call the cancer prevention vaccine.

MD Anderson doctors are working to stop HPV-related diseases by increasing awareness and accessibility to the cancer prevention vaccine

Larissa Meyer, M.D., stares out her office window at the vast landscape of the Texas Medical Center. She’s sad, angry and, above all, frustrated.

Meyer, a gynecologist, has just informed a 30-year-old woman with cervical cancer that her disease is terminal. The patient’s main worry is how her two young children will fare without her.

“This is so heartbreaking and so unnecessary,” Meyer says. “Unlike some other female cancers, cervical cancer is almost always 100 percent preventable.”

Yet Meyer sees this scenario over and over again.

Women in their 20s and 30s, many who have small children and are the pillars of their families, arrive in her office complaining of pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding. By the time symptoms appear, the cancer often has progressed and spread to other parts of the body.

“It’s tragic that women are still diagnosed with this disease,” says Meyer, an assistant professor in Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine at MD Anderson. “Cervical cancer should be obsolete by now.”

Obsolete because since the 1940s, Pap tests have been successfully detecting cervical cancer in its early stages, before it has a chance to spread. When caught early, the disease is highly curable.

Thanks to the Pap test, cervical cancer rates have gone down overall, but among the poor and uninsured who have difficulty accessing care, the disease continues to take a toll.

“Lack of insurance, lack of transportation, lack of information — whatever the reason, some women don’t avail themselves to this simple and lifesaving test,” Meyer says.

First Anti-Cancer Vaccine

Today, yet another weapon has been added to the cervical-cancer fighting arsenal, and Meyer is determined to make sure everyone knows about it.

A vaccine that blocks transmission of the human papillomavirus (HPV) — the virus that causes almost all cervical cancer cases — promises to prevent most occurrences altogether. In extoling the vaccine’s benefits, American Academy of Pediatrics president Thomas McInerny, M.D., dubbed it “the first anti-cancer vaccine.”

“How groundbreaking is that?” asks Lois Ramondetta, M.D., a gynecologist and professor in Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine.

Like Meyer, Ramondetta is on a mission to wipe out cervical cancer.

“We’ve got the Pap test, now we’ve got the HPV vaccine. There’s absolutely no justification for this disease to exist today. Every time I see another case, I think, ‘this is inexcusable,’” says Ramondetta.

But like the Pap test, the HPV vaccine, which was introduced in 2006, has been slow to be embraced.

“That’s a dangerous mistake,” says Ramondetta. “If you think you won’t contract HPV, think again.”

Had sex? You’ve probably had HPV

The human papillomavirus holds the dubious distinction of being the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States.

“Eighty percent of women and men — pretty much anyone who’s had sex — have been infected at one time or another,” Ramondetta says.

Through sexual activity, more than 40 strains of HPV can be passed along. These strains are split into two categories: those that cause cervical and other forms of cancer, and those that cause genital warts.

Two strains — HPV 16 and 18 — are blamed for the majority of cervical cancer cases, as well as most anal cancers and a large share of vaginal, vulvar and penile cancers. The strains can also cause cancers in the back of the throat, most commonly at the base of the tongue and in the tonsils, in an area known as the oropharynx. These are called oropharyngeal cancers.

Two other strains — HPV 6 and 11 — cause most genital warts. Though unsightly and contagious, warts won’t turn into cancer, even if they remain untreated. Without treatment, warts can multiply, stay the same or disappear altogether.

Most people infected with HPV will never get cancer or warts. Their bodies will clear the virus, usually over the course of two years, and they’ll never realize they were infected. During this phase of unawareness, those infected may unknowingly pass the virus along to others.

But in a small number of people, the virus persists and remains in the cells.

The longer the virus lingers, the more likely it is to cause cancer by doing what it does best — slowly and silently causing cells to grow abnormally. Ramondetta says progression from time of HPV infection to full-blown cancer can take five to 10 years, or even longer.

“This means your actions as a youth can have consequences in adulthood,” she warns. “About the time you get married or start a family or new career, you can be diagnosed with an HPV-related cancer.”

When HPV invades the cervix and causes cells to become precancerous, Pap tests can flag the abnormal cells before cancer develops, and doctors can intervene to return a woman to health. A second test, approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011, detects the presence of the HPV virus that causes the cells in the cervix to change. This test, when performed in conjunction with the Pap test, provides a powerful one-two punch in the war against cancer.

“Cervical cancer would be virtually unheard of if these two tests were used in tandem with the vaccine,” Ramondetta says.

The other HPV-linked cancers

While cervical cancer can be detected with screening, no effective screening tests exist yet for the other cancers linked to HPV: vaginal, vulvar, penile, anal and oropharyngeal cancers.

Cathy Eng, M.D., has seen a steady increase in anal cancer cases nationwide, up from 3,500 to 7,000 per year. And that number is rising.

“A number of these patients are living with HIV/AIDS. Their compromised immune systems prevented them from fighting off the HPV virus,” says Eng, associate professor in Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology. “Despite the use of drugs that suppress the HIV virus, the risk of anal cancer has not declined.

Furthermore, Eng says many patients with HIV/AIDS are older than 26, the FDA’s cutoff for those with weakened immune systems to receive the HPV vaccination.

Given that patients with HIV/AIDS are living longer today than in years past, Eng believes there may be an association between longevity and the increase in anal cancer cases.

Meanwhile, oropharyngeal cancers that affect the back of the throat are also dramatically increasing in numbers, says Erich Sturgis, M.D., associate professor in Head and Neck Surgery. Since the late 1980s, cases are up by 225%, with heterosexual middle-aged men accounting for the lion’s share of cases. Researchers associate this rise with the sexual revolution of the late 1960s and ’70s, and the increase in oral sex among heterosexual couples.

“Until this millennium, most oropharyngeal cancers were caused by smoking and alcohol use,” Sturgis says. “But now, more than 70 percent of these cancers have been shown to be HPV related.”

“These are serious cancers,” Sturgis says. “Treatments are typically painful, difficult and have many long-term side effects.“It’s scary that there are no routine screening tests for these cancers,” he says, “which are on the rise.”

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted virus in the United States. Almost every sexually active person will acquire HPV at some point in their lives.

Thank you, Michael Douglas

If you own a TV, radio or computer, you probably heard the furor over actor Michael Douglas’ statements to a British newspaper in June 2013 about his throat cancer. (It was later revealed to be oropharyngeal cancer affecting the base of his tongue.) The Guardian reported that when he was asked if he regretted his “years of smoking and drinking, usually thought to be the cause of the disease, Douglas replied, ‘No, because without wanting to get too specific, this particular cancer is caused by HPV … .’”

“Michael Douglas did us all a favor by raising awareness about human papillomavirus,” Sturgis says.

Although HPV-related cancers are on the rise, they’re still rare compared to breast, prostate and lung cancers. But experts say more could be done to prevent them — including boosting vaccination rates among young people.

“We have a vaccine that’s safe and effective,” Sturgis says. “And it’s being underused, especially in boys.”

Only about 14% of boys under age 18 are getting the complete three-dose vaccination, compared to 38% of girls, Sturgis says. This is in part because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) only updated its guidelines in favor of immunizing boys in 2011, while recommendations to vaccinate girls have been in place since 2006.

Vaccinating boys for HPV is also likely to benefit girls, Sturgis adds, by reducing the spread of the virus.

Though the Affordable Care Act requires insurers to cover the vaccine and the uninsured can get the vaccine at no cost through the federal Vaccines for Children program, the majority of Americans remain unvaccinated.

Why don’t people take this simple precaution that can save their lives? According to Ramondetta, several reasons exist.

Nearly 80 million people in America (one in four) are currently infected with HPV.

Getting through to parents

The HPV vaccine doesn’t cure HPV, it only prevents it. So to be effective, the vaccine needs to be given before a person becomes sexually active.

The CDC recommends vaccinating boys and girls at the age of 11 or 12 to give them time to build up immunity against the virus before they begin sexual activity.

That makes some parents squeamish. They fear that saying “yes” to the HPV vaccine will also encourage their children to say “yes” to sex at an early age.

“This is not to say that your preteen is ready to have sex,” Ramondetta says. “In fact, it’s just the opposite — it’s important to get your child protected from a cancer that may occur later in life before he or she ever thinks about sex. This is about protecting your child against cancer.”

She also points to a recent study in the journal Pediatrics that shows adolescent girls who receive the HPV vaccine are no more likely to show signs of sexual activity than girls who aren’t vaccinated.

“The HPV vaccine doesn’t open the door to sex,” Ramondetta assures reluctant parents. “It closes the door to cancer.”

There’s one more upside to getting the vaccine at a young age, Ramondetta says. Studies show the body assimilates the vaccine best in the preteen years, when the immune system is “revved up.”

Though 11 and 12 are the ideal inoculation ages, the vaccine is available to males and females as young as age 9. And it’s offered to males through age 21 and females up to age 26.

The CDC also advises men and women with weakened immune systems, including those with HIV/AIDS, as well as gay and bisexual men, to get vaccinated through age 26, providing they didn’t get fully vaccinated when they were younger.

“Even if you’ve already had sex, remember, the vaccine protects against more than one strain of HPV,” Ramondetta says. “You may be infected with one strain only, so the vaccine will protect you against the additional strains. Cover your bases, get vaccinated.”

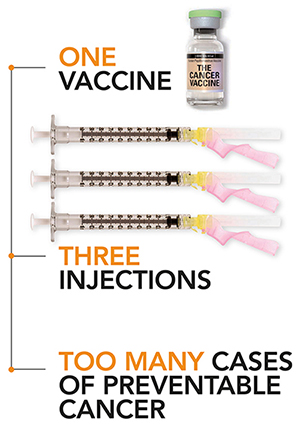

Not a one-shot proposition

The HPV vaccine isn’t a one-and-done process. It’s administered in three doses over six months. After the first shot, a second is required one or two months later. After the second shot, a third is required four to five months after that.

“To develop maximum immunity, it’s important to receive all three doses,” Ramondetta stresses.

Yet doctors report they’re finding it difficult to finish out the series for most children.

“It’s shameful that in the U.S., the richest country in the world, we can’t vaccinate against cancer,” says Meyer, who teams with Ramondetta to promote vaccinations for “patients, patients’ children, employees, family members and anyone who will listen.”

She says the required time lapse between shots is a major culprit behind the failure to finish out the three-shot series.

“Parents get busy at work, kids get busy at school and everyone forgets it’s time to return to the doctor’s office.”

To counter this, Meyer is piloting a reminder program in which pediatricians at The University of Texas Medical School in Houston send postcards, text messages and emails to alert parents that their children’s shots are due. A public education campaign using social media channels like Facebook and Twitter also is in the works.

Lately, she’s been giving parents refrigerator magnets equipped with built-in timers that “count down” the days between inoculations and flash conspicuously when it’s time for another shot.

Messages and magnets help, but to make a significant dent in America’s dismally low HPV vaccination rate, Meyer says shots should be given to children at school. In Australia, where this model is used, more than 70% of girls have completed the three-dose course. Not surprisingly, Australia’s HPV infection rate has dropped significantly. In 2013, the country extended the program to include boys.

Schools and pharmacies are convenient alternatives to doctors’ offices for the HPV vaccine, according to a recommendation this year from the President’s Cancer Council. And Meyer wholeheartedly agrees. She hopes to pilot an HPV vaccination program in a Houston school soon.

“Make it convenient. If people won’t come to the vaccine (in the doctor’s office), bring the vaccine to people. Whatever it takes, just do it.”

The HPV vaccine comes in two brands: Gardasil, manufactured by Merck and approved by the FDA in 2006, and Cervarix, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline and approved by the FDA in 2009. Both protect against cervical, anal, vulvar, vaginal, penile and oral cancers. Only Gardasil, the most widely used vaccine, offers added protection against the HPV strains most likely to cause genital warts, and only Gardasil is approved for females and males.

Gardasil manufacturer Merck is working on a future vaccine that will prevent transmission of nine strains of HPV — five more than its current vaccine. However, Lois Ramondetta, M.D., warns against waiting.

Image problem

The HPV vaccine has an image problem, Meyer says.

“Process should’ve been introduced from the beginning as a cancer-fighting vaccine, not a sexually transmitted diseases vaccine.”

Meyer points out that gynecologists were the first to receive shipments of the vaccine to give to their patients, when in fact, pediatricians should’ve been first in line.

“Remember,” she says, “the target audience is 11- and 12-year-olds.”

When the vaccine eventually arrived at pediatricians’ offices, the pediatricians received virtually no guidance on how to talk to parents about why their children should be vaccinated. Because HPV is usually diagnosed in adults, pediatricians’ experience with it may be limited, Meyer says. Consequently, they may unknowingly be giving the vaccine the “short shrift.”

Meyer and Ramondetta joined a CDC & speaker’s bureau that educates pediatric societies about HPV and helps pediatricians develop talking points to use in their discussions with parents.

“It’s disheartening,” Meyer says. “I’ve been a member of the bureau for more than a year, and not once have I been asked to give a talk.”

Compared to other countries, the U.S. does a stellar job administering neonatal vaccines, Meyer contends. Parents and providers are engaged and “on board” to get babies vaccinated. But when children become preteens, the commitment levels drop off.

Meyer recommends bundling the HPV vaccine with the two vaccines that are required at age 11 before kids can enter middle school — Tdap, which protects against tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis, and the meningococcal vaccine, which protects against meningitis.

To date, only Washington, D.C., and Virginia have enacted legislation requiring students entering the sixth grade to be vaccinated against HPV.

Wake-up call

“Even though the U.S. is doing an inadequate job of vaccinating kids for HPV,” Meyer says, “our efforts still make a difference.”

A Journal of Infectious Diseases study published in June 2013 revealed that since the HPV vaccine was introduced in 2006, infections have dropped 56% among U.S. girls ages 14 to 19, even though only slightly more than one-third are fully vaccinated.

This report provides irrefutable evidence that the HPV vaccine works, Meyer says.

“The report should serve as a wake-up call to our nation to protect the next generation from cancer by improving HPV vaccination rates,” she says. “We have the vaccine, we know it works, the science has been done. Now we just need to get it out there.”

Each year, about 21,000 cases of HPV-related cancers could be prevented by getting the HPV vaccine.