A golden beacon

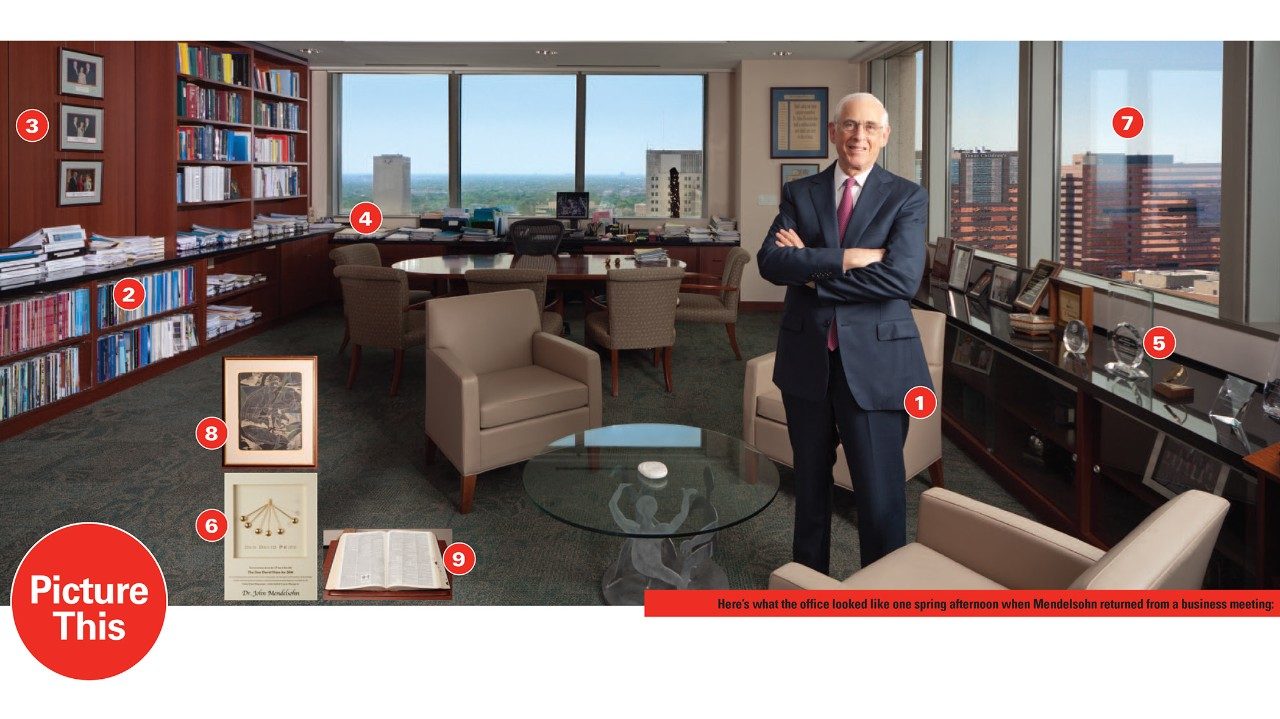

When John Mendelsohn, M.D., returns to research at MD Anderson, he’ll open a new chapter in his career at a cancer center vastly different from the one he came to Houston to lead in 1996.

Then known principally for its high-quality patient care, MD Anderson under Mendelsohn’s leadership heightened that clinical reputation, built up biomedical research and became a leader in connecting laboratory findings to patient treatment.

“John has done a tremendous job transforming MD Anderson into a cancer center with strong, research-driven patient care through an outstanding translational research effort,” says Waun Ki Hong, M.D., head of the Division of Cancer Medicine and a leader in personalized cancer treatment.

Research expenditures jumped more than threefold, from $121 million in 1996 to $547 million in 2010. MD Anderson became the nation’s leading recipient of grants from the National Cancer Institute, greatly increased institutional research funding from clinical operations and boosted external funding via philanthropy.

Space for research expanded with construction of the George and Cynthia Mitchell Basic Sciences Research Building and creation of the South Campus. It’s home to four state-of-the-art buildings and the Red and Charline McCombs Institute for the Early Detection and Treatment of Cancer.

An innovative commitment to prevention research built what is now the Dan L. Duncan Building to house the Division of Cancer Prevention and Population Sciences and established the Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment to support research.

A strategic system of institutes and centers brings together scientists and physicians across MD Anderson departments to focus on critical areas of research.

A passion for research spurs progress

“John Mendelsohn has always known that research is important. Just look at his background,” says Mien-Chie Hung, Ph.D., vice president for basic research.

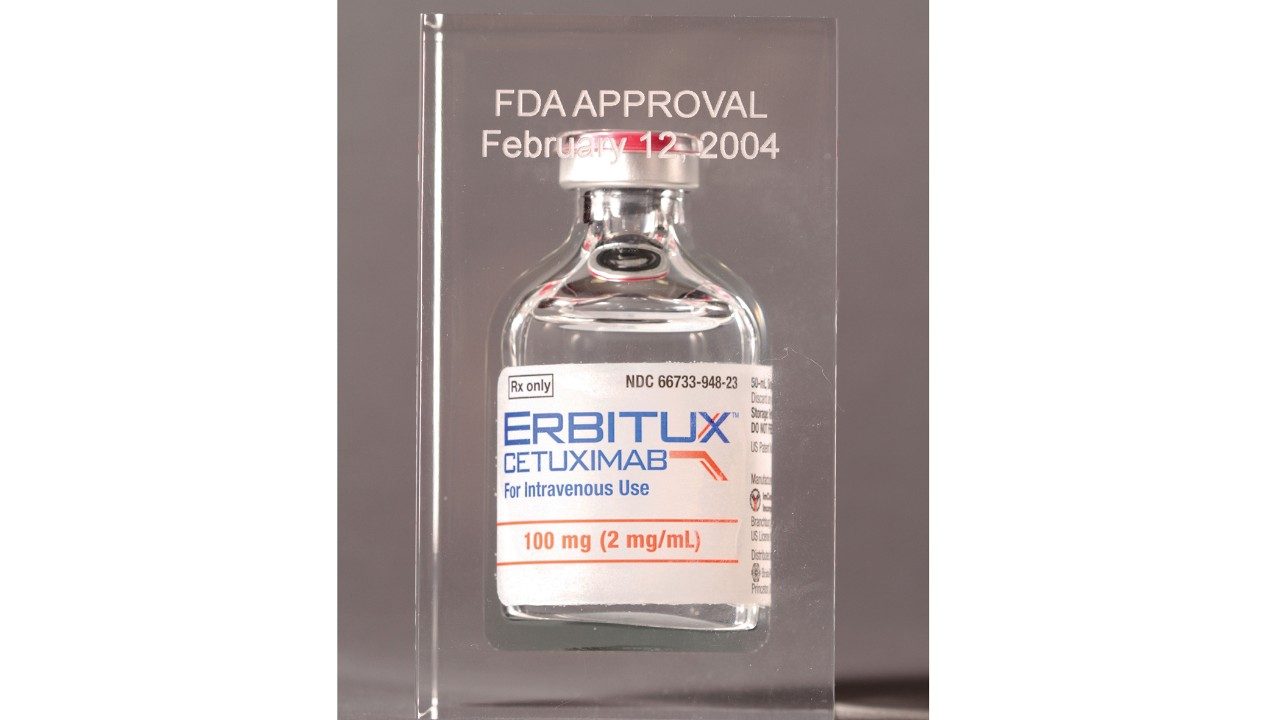

By the time Mendelsohn arrived at MD Anderson, he had pioneered the field of targeted therapy, taking an entirely new type of cancer drug from basic research concept all the way to the clinic.

“John had the translational research vision to build the South Campus program,” Hung says. “In addition to bringing in accomplished scientists, he created an environment to promote research excellence. One example is his support of the Institute for Basic Science with seven centers focusing on different aspects of cancer biology. And published research has almost doubled in the last decade.”

As a stand-alone cancer center, MD Anderson started out at a disadvantage in basic science, says Richard Schilsky, M.D., professor of medicine and section chief for hematology/oncology at the University of Chicago and chair of MD Anderson’s external advisory board for research programs and initiatives.

Other cancer centers are based in universities and benefit from the basic science programs present at medical schools. MD Anderson lacked that connection.

“Basic science components have been strengthened,” Schilsky says. “John recruited great people and has developed a great program. In many ways, MD Anderson is in front of the field in translational research and in prevention research in particular.”

Schilsky cites the BATTLE clinical trial for lung cancer, which relied on biopsies of patients’ tumors, swift analysis of those biopsies to identify drug targets, and then matched tumor to targeted treatment. “BATTLE established a new paradigm for the way to do drug and biomarker co-development,” he says.

“Today, MD Anderson has the most innovative clinical trials with the most interesting drugs,” Schilsky says. “It has enormous capacity to develop its own drugs based on targets identified in its own labs and the ability to bring them all the way to patients.”

SPORE grants underpinning of research

The gold standard of translational research is the Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) grant awarded by the National Cancer Institute. These large grants to teams of clinicians and scientists move discoveries on to clinical trials.

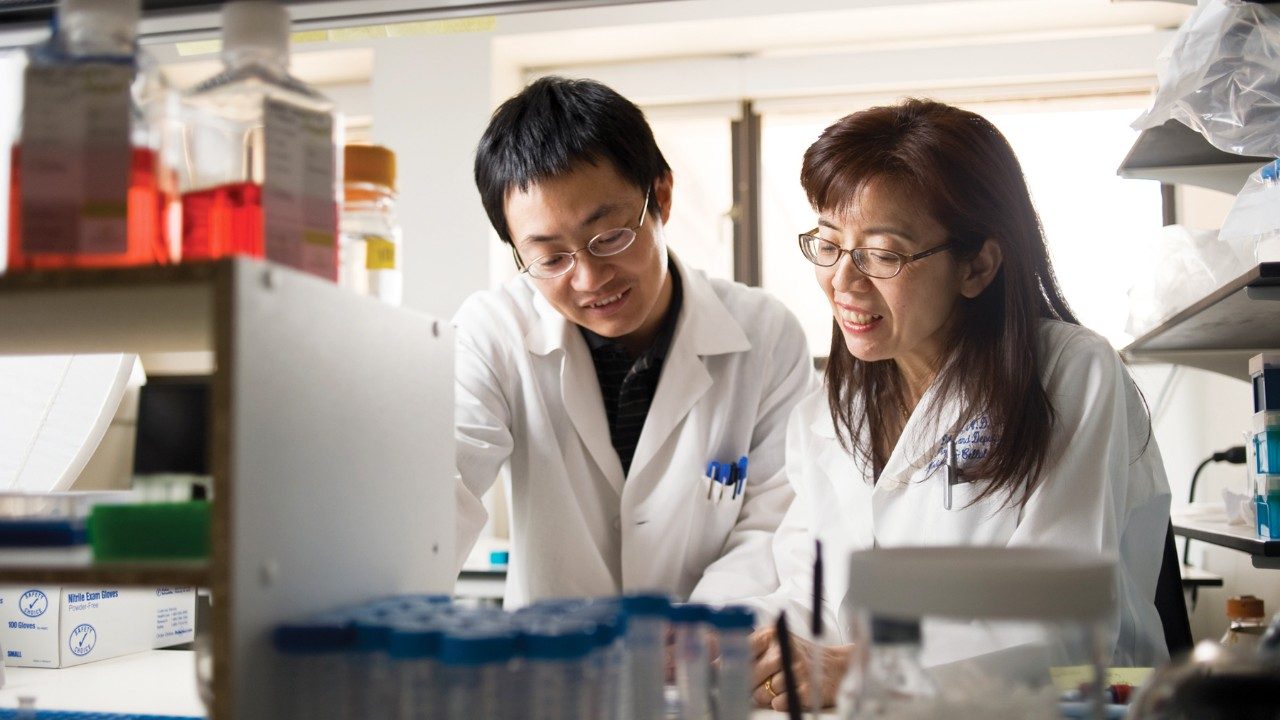

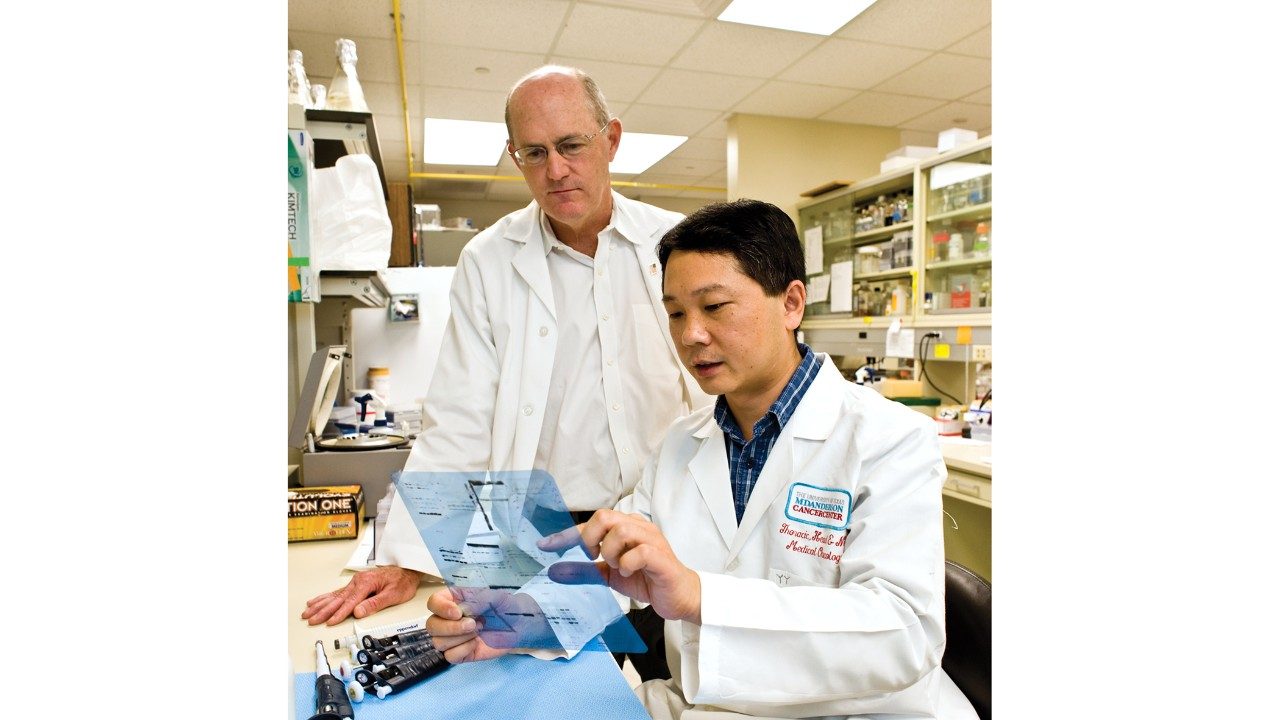

Basic and translational research at MD Anderson

have greatly expanded during the past 15 years.

Photo: John Smallwood

When Mendelsohn arrived, MD Anderson had two SPOREs, says Hong. “Now we have 12.” There are only 67 active SPOREs nationally.

Hagop Kantarjian, M.D., chair of the Department of Leukemia, has worked for each of MD Anderson’s first three full-time presidents.

“Dr. Mendelsohn expanded our basic and translational research tremendously, strengthening our reputation, visibility and the power of our research,” he says. “He’s one of the hardest working people I know. Almost every evening he’s out with philanthropists trying to convince them to support projects and issues important to MD Anderson.”

Leukemia made a number of seminal discoveries during Mendelsohn’s tenure, Kantarjian says. “This has been our golden period.”