Supportive care teams help dying cancer patients

Easing symptoms, fulfilling wishes at the end of life

Taylor Brown was too young to have a bucket list.

In late December 2011, the 29-year-old parts manager for a Baton Rouge, La., trucking firm began to have disabling pain in his lower back.

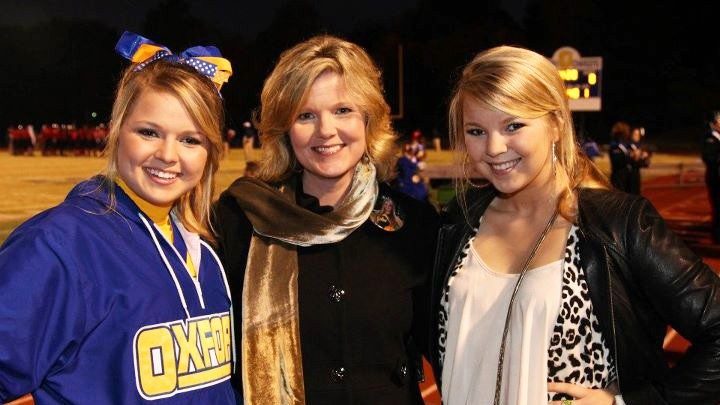

Diagnosed with an aggressive tumor in his sacrum that had spread throughout his body, he died March 23, 2012. But not before marrying the love of his life, Donia Crouch Brown.

“We’d been engaged for two years,” says Brown, 26. “Getting married was an easy decision — we were in love.”

It wasn’t the big wedding the couple had planned, but the small ceremony arranged by the staff of MD Anderson’s Andreas Beck Inpatient Palliative Care Unit was lovely and meaningful, according to Brown.

“Everybody gets a soul mate, and Taylor was mine,” she says.

Delicate balance between treatment and quality of life

In the United States, a surprising number of patients spend time in the intensive care unit or receive curative treatment in the last week of their lives, at great cost to them, their families and their health care teams.

Instead, at MD Anderson about 500 patients a year are admitted to an inpatient palliative care unit affiliated with the Department of Palliative Care and Rehabilitation Medicine. Patients are referred by their oncologists because side effects have caused them severe distress or treatment has become ineffective.

The goal of a stay on the 12-bed unit is stabilization of symptoms, then preparation for the next stage of care. Some return to treatment, but about one-third of those admitted die there. Another 30% to 50% are discharged to hospice at home or offsite.

First, members of the team address the patient’s physical and psychological symptoms. These may include pain, fatigue, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, lack of appetite, dyspnea (labored or difficult breathing) and difficulty sleeping.

Once these symptoms are under control, team members speak with patients about their end-of-life goals.

“We ask them their understanding of their disease,” says David Hui, M.D., a medical oncologist, palliative care specialist and assistant professor in the Department of Palliative Care and Rehabilitation Medicine.

“We find out what they know and what they hope to achieve in the time they have left. Sometimes our job is helping them understand the state of their illness.”

Some patients express regret that they won’t be able to achieve goals, such as Taylor Brown’s wish to marry Donia.

Fulfilling goals at the end of life

There have been several weddings on the unit.

One was the subject of a paper published in June in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. It proposed that the team’s help in fulfilling a terminal patient’s wish to marry her fiancé helped alleviate her distressing physical and psychological symptoms during her stay on the unit.

There was significant improvement in her pain, difficulty with walking and breathing after the wedding. As she’d hoped, she was discharged to home hospice and able to spend Christmas with her loved ones. She died two weeks later.

Martha Aschenbrenner is a program manager on the unit. A therapist with years of experience at MD Anderson Children’s Cancer Hospital, her specialty is helping patients communicate with their children — or deal with the sorrow of leaving them.

She meets with patients and their children on several occasions, if possible. Many patients are concerned with how they’ll be remembered and want to ensure that their children will know how much they were loved.

But encouraging patients to leave a legacy — for example, a video or audio recording for their children before they die — may be unnecessarily stressful.

“It’s just putting one more expectation on them,” Aschenbrenner says. Instead, she might suggest that a loved one write an account of the parent’s last days or of the discussions they had.

‘We’re privileged’

Working on the unit can be difficult and would be impossible without daily meetings — lively and sometimes intense updates on each patient in the unit.

Team member Steven Thorney, chaplain in the Department of Chaplaincy and Pastoral Education, calls their work transdisciplinary.

“We each have our specialty, and each is valued. We share the stress and the work,” he says.

Despite the strains, he says team members feel lucky to work on the unit.

“It’s an emotional time,” he says. “Patients want their loved ones near — to say thank you, or I’m sorry, or please forgive me, or I love you, or goodbye. The things we’re privileged to see are extraordinary.”