Top four questions I receive about cancer survivorship care

I can normally tell within the first 2-3 minutes of meeting someone if they’ve received the proper orientation about what to expect from me and/or survivorship care.

When they haven’t, their questions tend to run along the lines of, “Who are you?” “Why am I seeing you instead of the doctor who's been treating me for the past four years?” and “How are you associated with the Endocrine Center?”

Alcohol affects sleep – here's how

Top four questions I receive about cancer survivorship care

Teen’s ‘powered by people’ presentation highlights mother’s experience at MD Anderson

How can you tell if a mole is cancerous?

Tips for using AI to find cancer information

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

|---|

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

|

Healthy Living

|

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

Find stories by topic

Find out everything you need to know to navigate a cancer diagnosis and treatment from MD Anderson’s experts.

Should you be getting regular mental health checkups?

July 07, 2025

10 thyroid myths you shouldn’t believe

July 02, 2025

Vasectomy and prostate cancer risk: What you should know

June 26, 2025

5 little-known breast cancer facts

June 24, 2025

Preventing and managing caregiver burnout

June 23, 2025

Read inspiring stories from patients and caregivers – and get their advice to help you or a loved one through cancer.

Astrocytoma survivor gives back to MD Anderson

July 03, 2025

Lymphoma survivor uses AI to help explain her treatment

June 20, 2025

Get MD Anderson experts’ advice to help you stay healthy and reduce your risk of diseases like cancer.

Alcohol affects sleep – here's how

July 15, 2025

How can you tell if a mole is cancerous?

July 11, 2025

Can breastfeeding really lower your breast cancer risk?

July 08, 2025

Is BMI the best body weight calculator?

July 01, 2025

5 little-known breast cancer facts

June 24, 2025

What should you look for in a sun hat?

June 19, 2025

6 ways to cope with scanxiety

June 17, 2025

Do weighted vests benefit your fitness routine?

June 16, 2025

Learn how MD Anderson researchers are advancing our understanding and treatment of cancer – and get to know the scientists behind this research.

Using math to answer cancer’s biggest questions

July 09, 2025

What causes chemobrain? New insights

June 03, 2025

Nutrivention: Food as medicine

May 28, 2025

5 emerging therapies presented at ASCO 2025

May 28, 2025

Top 5 MD Anderson abstracts at AACR 2025

April 25, 2025

Cell therapy: The evolution of the ‘living drug’

April 22, 2025

How non-scientists are helping cancer researchers

February 21, 2025

Read insights on the latest news and trending topics from MD Anderson experts, and see what drives us to end cancer.

Tips for using AI to find cancer information

July 10, 2025

What is a Living Will?

June 06, 2025

Surgeon-scientist: ‘MD Anderson is unique’

May 15, 2025

Find out what inspires our donors to give to MD Anderson, and learn how their generous support advances our mission to end cancer.

Mom's legacy lives on through fundraising for MD Anderson

April 28, 2025

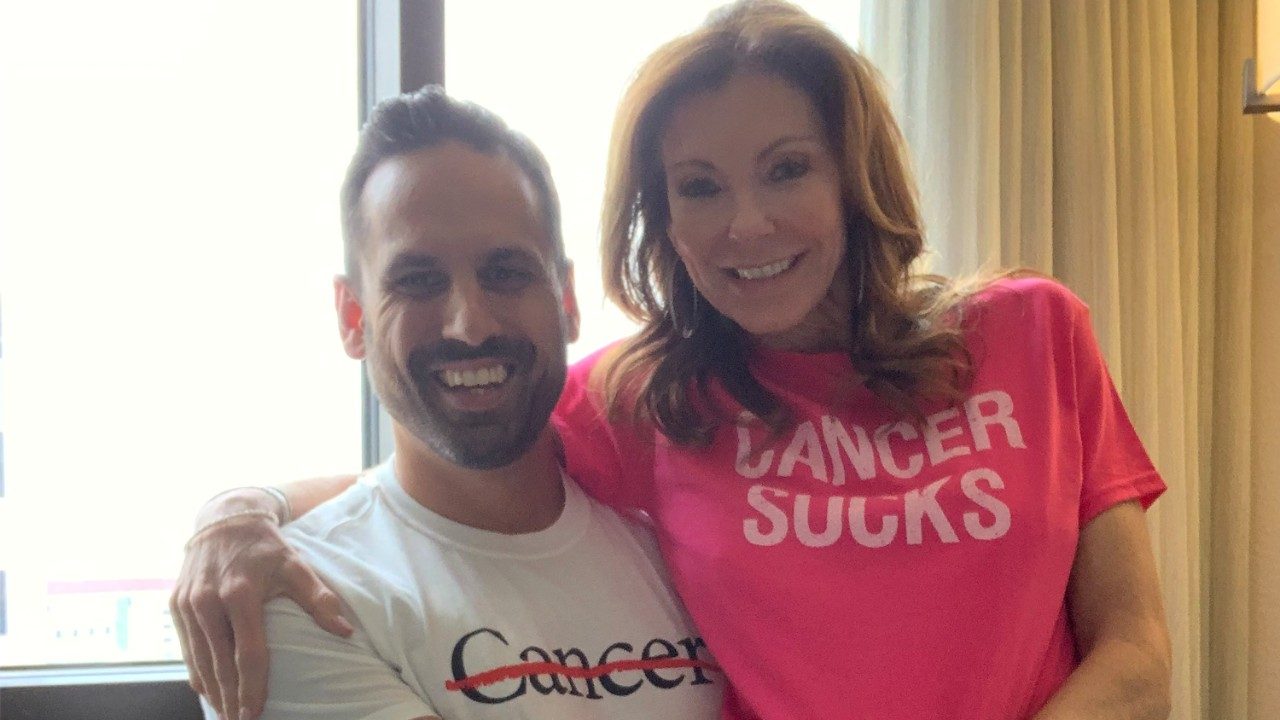

Three cancer survivors raise funds to support Colorado patients

October 03, 2024

Inflammatory breast cancer survivor finds hope at MD Anderson

October 24, 2023