10 thyroid myths you shouldn’t believe

Have you ever heard that people with thyroid disorders shouldn’t eat certain vegetables? Or that you can treat an underactive thyroid gland with iodine supplements, and other thyroid disorders with hormone supplements?

If so, you’re not alone. The only problem? None of these claims is accurate. So, before you take any action based upon them, we want to set the record straight on these and seven other common thyroid myths you might’ve heard.

Astrocytoma survivor gives back to MD Anderson

10 thyroid myths you shouldn’t believe

Is BMI the best body weight calculator?

Advice for managing anxiety after completing cancer treatment

Six nurses reflect on MD Anderson’s sixth Magnet designation

Dermatologist: How to deal with targeted therapy-related skin rashes

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

|---|

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

|

Healthy Living

|

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

|

Diagnosis & Treatment

|

Find stories by topic

Find out everything you need to know to navigate a cancer diagnosis and treatment from MD Anderson’s experts.

10 thyroid myths you shouldn’t believe

July 02, 2025

Vasectomy and prostate cancer risk: What you should know

June 26, 2025

5 little-known breast cancer facts

June 24, 2025

Preventing and managing caregiver burnout

June 23, 2025

Anoscopy explained: Purpose, process and results

June 19, 2025

6 ways to cope with scanxiety

June 17, 2025

Read inspiring stories from patients and caregivers – and get their advice to help you or a loved one through cancer.

Astrocytoma survivor gives back to MD Anderson

July 03, 2025

Lymphoma survivor uses AI to help explain her treatment

June 20, 2025

Get MD Anderson experts’ advice to help you stay healthy and reduce your risk of diseases like cancer.

Is BMI the best body weight calculator?

July 01, 2025

5 little-known breast cancer facts

June 24, 2025

What should you look for in a sun hat?

June 19, 2025

6 ways to cope with scanxiety

June 17, 2025

Do weighted vests benefit your fitness routine?

June 16, 2025

Seeds: The ‘unsung hero’ of plant-based nutrition

June 13, 2025

Learn how MD Anderson researchers are advancing our understanding and treatment of cancer – and get to know the scientists behind this research.

What causes chemobrain? New insights

June 03, 2025

Nutrivention: Food as medicine

May 28, 2025

5 emerging therapies presented at ASCO 2025

May 28, 2025

Top 5 MD Anderson abstracts at AACR 2025

April 25, 2025

Cell therapy: The evolution of the ‘living drug’

April 22, 2025

How non-scientists are helping cancer researchers

February 21, 2025

4 questions with immunology researcher Susan Bullman

February 04, 2025

Read insights on the latest news and trending topics from MD Anderson experts, and see what drives us to end cancer.

Find out what inspires our donors to give to MD Anderson, and learn how their generous support advances our mission to end cancer.

Mom's legacy lives on through fundraising for MD Anderson

April 28, 2025

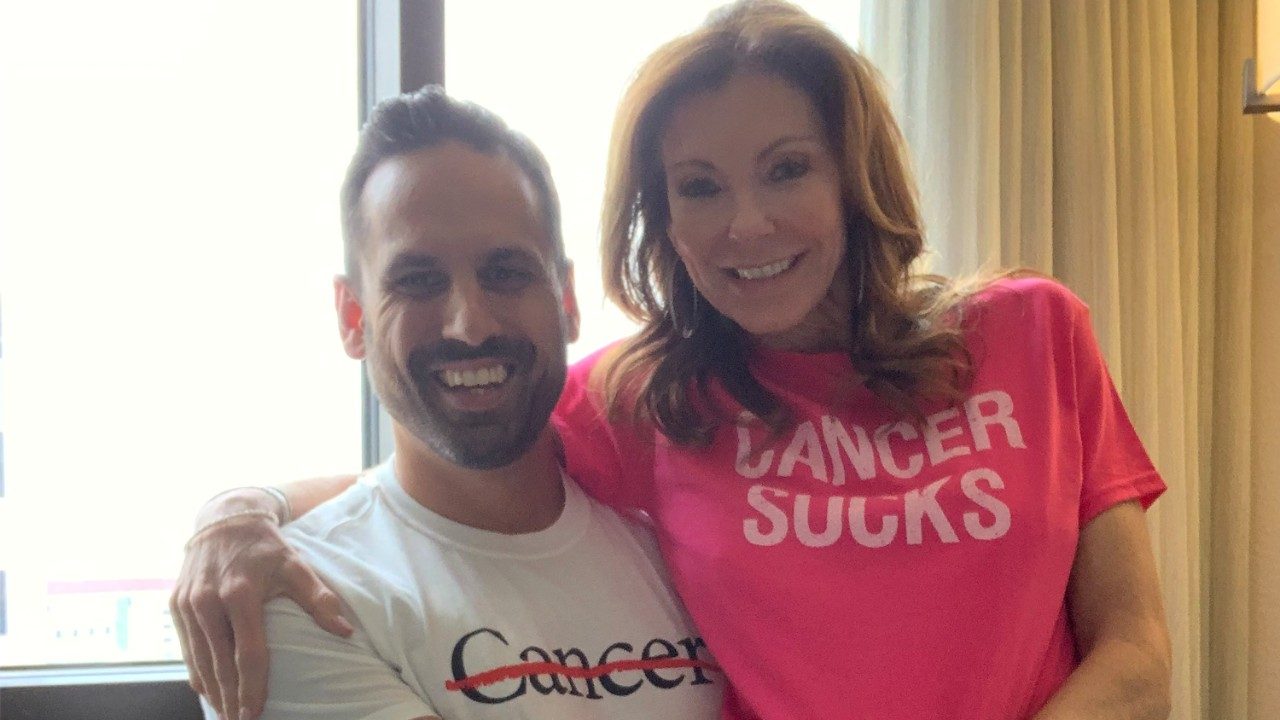

Three cancer survivors raise funds to support Colorado patients

October 03, 2024

Inflammatory breast cancer survivor finds hope at MD Anderson

October 24, 2023