- Diseases

- Acoustic Neuroma (14)

- Adrenal Gland Tumor (24)

- Anal Cancer (68)

- Anemia (2)

- Appendix Cancer (16)

- Bile Duct Cancer (26)

- Bladder Cancer (72)

- Brain Metastases (28)

- Brain Tumor (232)

- Breast Cancer (714)

- Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (2)

- Cancer of Unknown Primary (4)

- Carcinoid Tumor (8)

- Cervical Cancer (158)

- Colon Cancer (166)

- Colorectal Cancer (118)

- Endocrine Tumor (4)

- Esophageal Cancer (44)

- Eye Cancer (36)

- Fallopian Tube Cancer (8)

- Germ Cell Tumor (4)

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (2)

- Head and Neck Cancer (12)

- Kidney Cancer (128)

- Leukemia (342)

- Liver Cancer (50)

- Lung Cancer (286)

- Lymphoma (278)

- Mesothelioma (14)

- Metastasis (30)

- Multiple Myeloma (100)

- Myelodysplastic Syndrome (60)

- Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (6)

- Neuroendocrine Tumors (16)

- Oral Cancer (100)

- Ovarian Cancer (172)

- Pancreatic Cancer (160)

- Parathyroid Disease (2)

- Penile Cancer (14)

- Pituitary Tumor (6)

- Prostate Cancer (146)

- Rectal Cancer (58)

- Renal Medullary Carcinoma (6)

- Salivary Gland Cancer (14)

- Sarcoma (238)

- Skin Cancer (296)

- Skull Base Tumors (56)

- Spinal Tumor (12)

- Stomach Cancer (64)

- Testicular Cancer (28)

- Throat Cancer (92)

- Thymoma (6)

- Thyroid Cancer (98)

- Tonsil Cancer (30)

- Uterine Cancer (80)

- Vaginal Cancer (16)

- Vulvar Cancer (20)

- Cancer Topic

- Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Issues (20)

- Advance Care Planning (10)

- Biostatistics (2)

- Blood Donation (18)

- Bone Health (8)

- COVID-19 (362)

- Cancer Recurrence (120)

- Childhood Cancer Issues (120)

- Clinical Trials (632)

- Complementary Integrative Medicine (22)

- Cytogenetics (2)

- DNA Methylation (4)

- Diagnosis (232)

- Epigenetics (6)

- Fertility (62)

- Follow-up Guidelines (2)

- Health Disparities (14)

- Hereditary Cancer Syndromes (126)

- Immunology (18)

- Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (8)

- Mental Health (116)

- Molecular Diagnostics (8)

- Pain Management (62)

- Palliative Care (8)

- Pathology (10)

- Physical Therapy (18)

- Pregnancy (18)

- Prevention (918)

- Research (392)

- Second Opinion (74)

- Sexuality (16)

- Side Effects (604)

- Sleep Disorders (10)

- Stem Cell Transplantation Cellular Therapy (216)

- Support (402)

- Survivorship (322)

- Symptoms (182)

- Treatment (1786)

New surgical protocol for ovarian cancer is showing improved survival rates

3 minute read | Published March 11, 2015

Medically Reviewed | Last reviewed by an MD Anderson Cancer Center medical professional on March 11, 2015

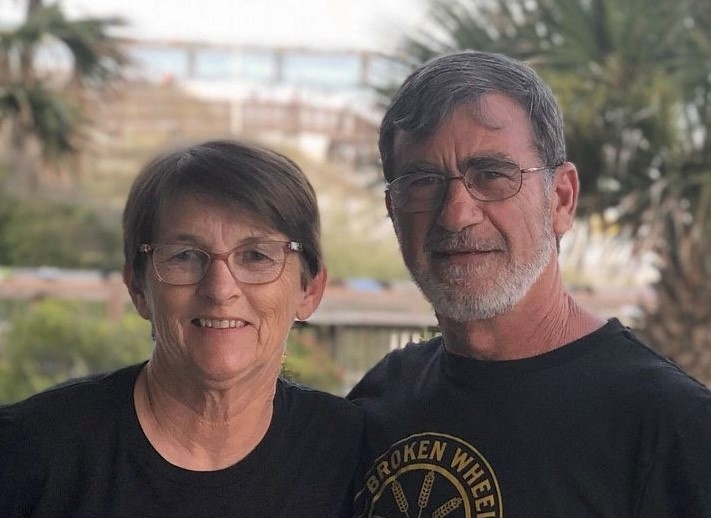

Triathlete and marathoner Leslie Russell teaches reading to children with dyslexia in the Spring Branch Independent School District. It’s a job she loves in the community where she grew up.

In the summer of 2013, Russell was blindsided when she learned what she thought was an exceptionally tenacious intestinal bug was actually stage 3 ovarian cancer.

After multiple trips to the doctor, including a gynecological exam, her misery led to an emergency room visit, a CT scan and, at last, a diagnosis.

“I would never have believed I have cancer,” Russell says. “I lead a pretty healthy lifestyle. It was a surprise.”

Russell came to MD Anderson, where she benefited from an early treatment innovation adapted and implemented through the Moon Shots Program, the institution’s ambitious effort to dramatically reduce cancer deaths.

About the time Russell first met with Kathleen Schmeler, M.D., an associate professor of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, the 21 oncologists in the department who treat ovarian cancer had agreed to follow a new protocol to guide treatment.

Personalized surgery

Previously, most new patients had surgery to explore the extent of their disease and remove as much of it as possible. Worldwide, this practice results in 20 to 30% of patients achieving “complete gross resection,” or removal, of all visible tumor. At MD Anderson, the rate was about 20%.

Using the new protocol, known as the Anderson Algorithm, all patients receive a minimally invasive laparoscopic evaluation during which two surgeons independently rank the distribution and spread of the disease to other organs. If the score is less than 8, patients proceed to surgery. If it’s greater, they receive chemotherapy before surgery.

The predictive index used in the protocol was developed by Anna Fagotti, M.D., and colleagues at Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Rome, based on the extent of disease observed in seven other organs via laparoscopy. A score of below 8 indicates for surgery first, while a score of 8 or above indicates presurgical chemo.

Ovarian cancer is hard to assess with imaging alone, Schmeler explains. “Ovarian cancer spreads almost like a coating across the organs, so it’s hard to see on CT scans. Laparoscopy really helps assess how much disease there is and where it is.”

Since surgeons began to apply the protocol, the rate of complete resection for patients who have surgery first has gone from around 20% to 88% (67 total patients), and for those receiving chemo first, it has improved from 60% to 86% (65 total patients). So far, the protocol has sorted half of patients to each mode of treatment. Faculty have adhered to the algorithm 95% of the time since it began two years ago.

“Achieving the greatest clinical impact that we can with existing knowledge is an important aspect of MD Anderson’s Moon Shots Program,” says Anil Sood, M.D., professor of Gynecological Oncology and Reproductive Medicine and co-leader of the Breast and Ovarian Cancer Moon Shot. “We worked hard to develop this protocol, but all of it is based on existing knowledge.”

A combination of surgery and chemotherapy is used to treat the disease, but the sequence of those therapies has been at issue for lack of clear indication of which should be used first. Practice at MD Anderson varied among physicians, Sood says.

“Our protocol allows us to take a more personalized approach to surgery with better results for our patients,” says Sood.

Russell’s score indicated a need for chemo first. “I had sprinklings of tumors all over my abdominal cavity,” she says.

Nine weeks of a chemo-drug combination of carboplatin and taxol greatly reduced the tumor burden, and the surgery that followed achieved complete removal of all visible cancer. Russell then had nine more weeks of chemo as a precaution.

The chemo slowed her a bit — she still worked out and ran, but didn’t enter races. “I also continued to teach, and being able to work with my students was hugely beneficial,” she says.

There was also fatigue and her hair thinned enough to make a baseball cap part of her daily wardrobe, but now she’s back on the bike, and running and swimming competitively.

“I was fortunate how well I responded. I feel really blessed,” she says.

Related Cancerwise Stories

photo by Eric Kayne

Achieving the greatest clinical impact that we can with existing knowledge is an important aspect of MD Anderson’s Moon Shots Program.

Anil Sood, M.D.

Co-leader of the Breast and Ovarian Cancer Moon Shot